Ask Greil: December 6, 2022

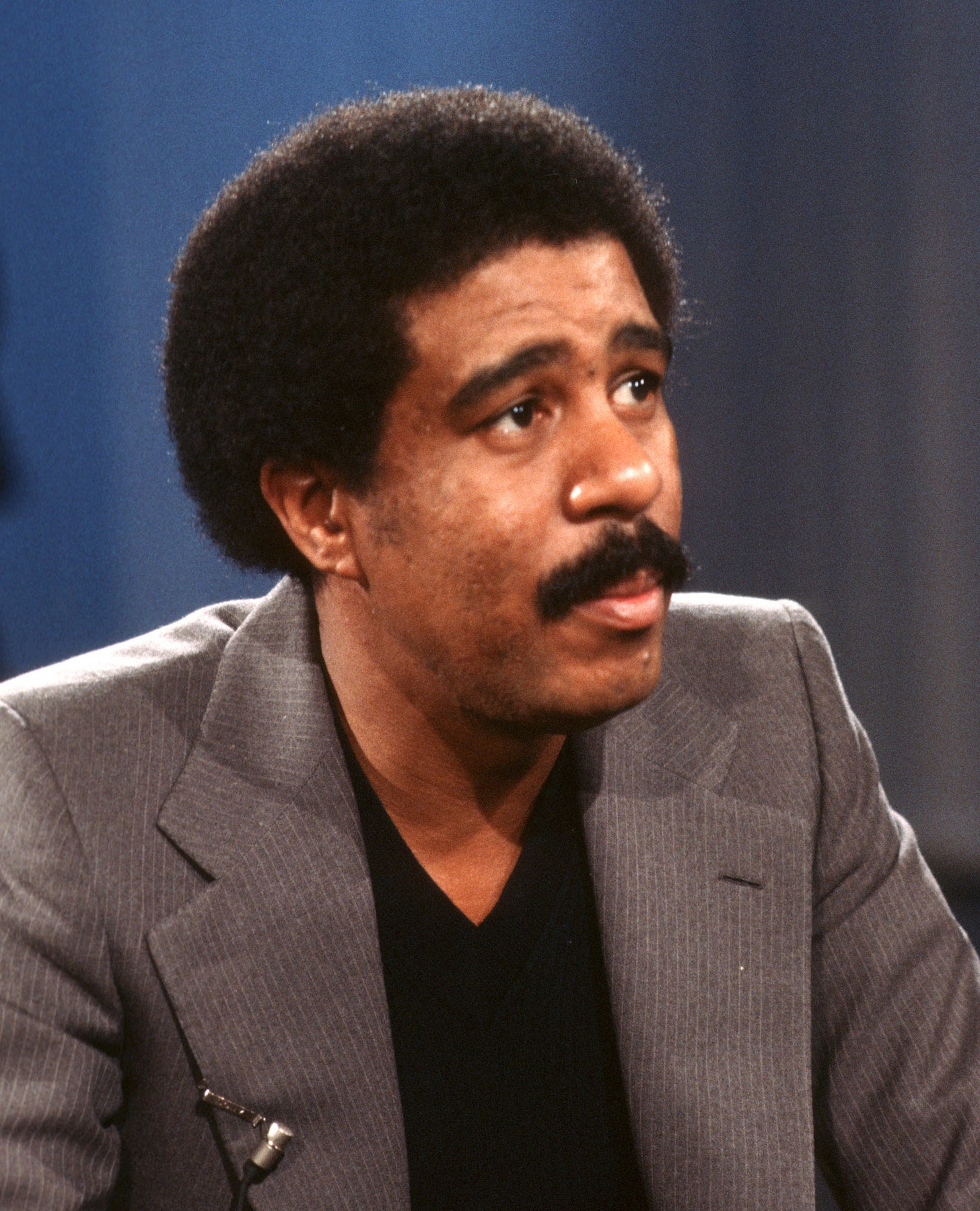

You’ve haven’t written much about Richard Pryor, but enough to indicate that he interests you. I was taken aback to learn that there have been at least five documentaries about him in the past decade, the best being 2014’s Omit the Logic. I think I understand the continuing fascination; we’re still digesting how sublimely disruptive he was at his best. When he was living in Berkeley in the early ‘70s, essentially reinventing himself professionally, doing gigs at Mandrake’s, and occasionally taking shifts on KPFA, how aware of him were you?

Best as always to you and yours. —DAN HEILMAN

I learned long ago that at one time or another everyone passes through Berkeley, usually well before I got interested in them, so I missed out on everything from Lettrist International member Patrick Straram, who was there just years before the fascination that led to Lipstick Traces took me over—we had many mutual friends but his name never came up and if it had when he was here it would have meant nothing to me—to Pauline Kael, who was programming movies daily in her theaters on Telegraph Avenue that provided my wife’s and my cinematic education , but we only met her and became friends after she’d moved to New York. Harry Smith built the record collection that led to Anthology of American Folk Music in Berkeley in the late ‘40s—admittedly I was at most five or six at the time—a foundation stone for my life’s work I didn’t discover until 1970. My later friend Cecil Brown was part of Richard Pryor’s crowd (or vice versa) in Berkeley where Pryor found and shaped his voice but he didn’t really come alive for me, even with early SNL and TV specials and Lily Tomlin, until I got his 2000 box set And It’s Deep Too and played all 9 CDs 100 times in a year. The immersion in country blues that took me over after Altamont was a true Berkeley scene just a few years before at the Albatross saloon [?Pub?] and the Berkeley Folk Festival but I didn’t realize the Berkeley-issued country blues compilations I was so obsessed with was real life on the other side of town. I could go on. The gist of it is that I always caught the train but only after it had left the station. Love in vain?

Regarding titans of ‘50s rock & roll still with us [“Ask Greil,” 11/10], last I checked (and I don’t care to check again), it turned out that not only was Ronald Isley still with us, but so was (improbably, delightfully) Huey “Piano” Smith!

Both “Dead Man’s Curve” and “Hotel California” use the phrase “last thing I remember,” and both are arguably structured as flashbacks. (Though with “HC” it’s not clear where the narrator is singing from—Hell, maybe?) Can this possibly be a coincidence? Is one meant to be one a version of the other? —MICHAEL DADDINO

Huey Smith has been a devout Jehovah’s Witness for nearly fifty years or more. That doesn’t mean he doesn’t count. I can’t believe Jerry Lee Lewis didn’t play “I Got the Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu” at least once.

Hard not to believe that “the last thing I remember” in “Hotel California” isn’t at least a subconscious echo from “Dead Man’s Curve,” even if Don Henley doesn’t say “Doc.” That would have been a fabulous touch. It’d sound like the whole song was some guy talking to his psychoanalyst.

Isn't Dion the real "last man standing"?

Did you ever encounter Philip K. Dick in your days in the Bay area? I hope you and your family have a great holiday season. All the best. —PETER

Dion is The One.

I don’t think I’d even heard of Philip K. Dick when he was in the Bay Area. To this day the only book of his I’ve read is The Man in the High Castle.

Not a question, but a comment. Just finished Folk Music. Wanted to thank you for the deep dive and wide-ranging reach. Of all the rivulets in the book, I was taken aback by the Dr. Tushmaker story. Hal Holbrook used it in Mark Twain Tonight; I assumed it was Twain's. —KEN VENICK

I didn't know it was part of the Holbrook show. Hey, maybe it was Twain's. I heard about it from a friend, looked it up, followed the story—never saw Twain's name with it, but who knows how many pseudonyms he used?

Hi Greil -- I'm so glad it seems like you're on the mend. I finished Folk Music last night, and loved everything about it, starting with the cover artwork, which is already on my short list of favorite Greil covers, right up there with the old Mystery Train clip art cover. Thanks especially for writing about "Jim Jones"—that's been my favorite performance on that record since I first heard it sometime in the late '90s, when I was in high school.

Following up on Chuck's 10/27 question regarding a hypothetical collection of RS, Creem, and Village Voice pieces from the '70s, count me in as someone who'd buy and read such a book in a heartbeat. I actually thought of compiling a PDF of stray pieces from GreilMarcus.net as I was preparing to go on a cruise about eight months ago, but after a whole lot of copy-and-paste it became clear that there were so many possible books here, with overlapping themes and subjects, and I bailed. (I reread Stranded and Geoff Dyer's But Beautiful on the boat instead.) Still, I'd love to have pieces like "Rock-a-Hula Clarified" and the Bicentennial piece in a tangible form.

(I'm getting to my question.) You've spoken before about writing Lipstick Traces during the Reagan years, referring to it in that interview with Simon Reynolds as a version of "leaving the country." I thought of that exchange and that relationship between books and presidents as I was rereading Under the Red White and Blue earlier this year, and Double Trouble shortly after that (actually right when the Dobbs ruling came out, talk about timing), and now Folk Music. I'm sure anyone reading Mystery Train at the time sensed Nixon's presence, although he was barely there in any explicit way, much like although Trump is rarely mentioned by name in Under... and Folk Music, his specter is inescapable.

So what, for you, was different about Trump? Your response, at least in book form, was/has been anything but "leaving the country"—these recent books are deeply and wonderfully American. Or maybe the better question is, what was different about Reagan? Or, what's different about you, now?

Thank you again for everything. Your work changed my life when I found Mystery Train at the library as a 13-year-old and wanted so badly to understand it that I kept checking it out for years, just opening it to random pages and looking at the words and trying to decode them. I'm thankful for the journey and for the fact that it's still in progress. —TOM

This is a good and deep question. It’s made me think hard and I’m not sure what the answers might be.

I lived through two terms of Reagan as Governor of California when it was still essentially a Republican state. As Governor, the fundamental cruelty of his character was never hidden, as it was when he was president. We saw him plain. I always understood him as a serious person who meant to transform the country and the world forever. So it wasn’t that for the whole of his presidency I fled the US for Europe, intellectually spiritually and more in terms of how I spent my time, mostly doing research in the libraries at Cal but also in several research trips to Paris, Amsterdam, and Zurich, but that I fled to Europe, as the little bubble people then had constructed and that I was reconstructing, in 1952.

Reaganism was for me a shock I couldn’t get over. A lot of that is in Lipstick Traces, and fairly explicitly. It had to do with the disappearance and demonization of the explosion of creativity in all fields of life in the 1960s and early ‘70s—and the way so many people caught up in that felt exiled in their own country when that ended. By the time Trump emerged—and I’d always seen him as a threat, foolishly thinking at the time of his first bankruptcy, We’ll, we don’t have to worry about what he might do to the country anymore—I was more cynical, and more prepared to stay here, in terms of thinking and writing, than I was before. I learned a lot about the country from Trump. I learned that what so horrified me and others about his policies and his demeanor—his evident contempt for all humanity, his clear belief, as someone put it, that he was the best person ever born—was what so thrilled so many people who did and still do embrace him as as a savior, and less the savior of the country (as in Make America White Again) than as a personal savior: if you can’t get away with anything—lie cheat and steal, defy rationality, elevate yourself above ordinary humanity by naming those who disagree with you your enemies who don’t deserve to speak or live, betray your spouse, take the money and run—you can vote for someone who can and feel a little of that glory, that freedom, rub off on you. Thinking over the history of the country, carefully, era by era, president by president, I came to the conclusion that in no tine in our history had support for democracy exceeded 65 percent, and that often it was barely 50 percent or even lower—because democracy is a burden, you have to make deep and hard choices that are more moral than narrowly political or self-interested, and many people would choose to have someone else, a ruler, an autocrat, even, as at the beginning of the republic, a Caesar who could designate his successor, make those choices for them. So I saw Trump as a part of America that had always been present, and that could only be stopped by the articulation of other versions of America. And in my own small way I found myself impelled to that kind of work, to engage with the promises and betrayal of the American project as well as I could. And have fun doing it, too, because for me writing, if it’s any good at all, is fun before and after it’s anything else. I’ve rarely had more fun writing than I did in the few pages on Skip James in a book ostensibly, and really, about The Great Gatsby. And I think those pages, in that context, say as much about my country as anything I’ve been lucky to come up with.

Get sick get well get out of the hospi-tel.

In your discussion [in Folk Music] of “Ain't Talkin',” the imagery of the garden and gardener are presented but we are not hammered over the head with it. I've always been taken with the coda chord as leading us to wonder if there might be one more chance for something other than darkness at the world's end. I might have missed it and in terms of the book I did miss it. Did I foolishly think I found one ray of light as a counter balance to the darkness? —TERRY GANS

It’s an open song. The cynicism and despair are clearly cultivated. There are moments of ordinary life amid the atmosphere of classical ruins and waste: “Someday you’ll be glad to have me around” just seems to sneak out from under the eye of the storyteller. The humor of the song, I really do believe, goes right back to Jack Scott’s world-stud tromping in “The Way I Walk.” That last chord so clearly says, “Play the song again. You haven’t heard it all.” And the rhythm is constantly shifting even as the patterns repeat, like waves coming in and out over a beach: you never know what they’re going to bring in. When I was 15 my family went to Hawaii. The very first day in the ocean, I had my glasses on, not swimming, just throwing a ball around. A wave knocked me down, my glasses were swept out to sea, and I spent the rest of the trip squinting and trying to see what I couldn’t. On our very last day, two weeks later, we were standing in the shallow surf when my glasses washed up. They weren’t damaged at all.

Putting aside contemporary record reviews and liner notes, what were the earliest long-form essays to focus on a single album? It’s difficult to find examples from before the publication of your 1979 collection, Stranded. Perhaps Lester Bang’s “The Greatest Album Ever Made” about Metal Machine Music from Creem in 1976? Do you know about or did you write any earlier examples? Thanks. —AARON CURRAN

I’m not sure what you mean by long-form. 1,000 words, 2,500, 10,000? God knows such things are all over the internet. See all the worthless explications of what this or that song really means…

I don’t have the knowledge to answer. I’m sure the answer goes back to the first albums of 78s in the ‘30s. But looking at context might help. At Rolling Stone in 1968-70 most reviews were 250-500 words—sometimes much less. But we often devoted an entire page to an album—and often with reviews of strong and unpredictable intellectual probing and playfulness. One of the first was Jann Wenner’s pan of Cream’s Wheels of Fire. There was my piece on The Rolling Stones’ Let Ut Bleed and David Bailey’s Goodbye Baby and Amen, which was probably the first piece of real writing I did. There was J. R. Young’s short story on Crosby Stills Nash and Young’s Deja Vu. They leapt out because their length and clear engagement with their subjects—and the design as much as their size signaled that the reader should be ready to take a deep breath and dive in.

Did you ever read Walter Mosley’s novel John Woman (2018)? While I never found a mention of it in the writings of yours I’ve seen, many of its themes seem relevant to your own takes on history and its fallacies of interpretation. —BEN MERLISS

That's one I started, and it didn't draw me in at all. But it could have been the wrong time and place. It seems like it's something I have to read and I will. Thanks for bringing it up, even if I have nothing to add.

Have you heard the new Bruce Springsteen album? I kind of understood why he wanted to be Pete Seeger, but I have no idea why he wants to be Southside Johnny. —CHUCK

I think Springsteen’s Seeger Session band was meant to honor Pete Seeger, to me a dubious proposition, even if he is right now on a new stamp. But that’s beside the point you’re not making.

When confronted with a wonderful song, something unexpected and unexplainable when first heard, and especially when retaining those qualities years or half a lifetime later, a writer’s impulse is to want to write about it, need to write about it, to get closer to the source, and maybe to pass that feeling, that desire, on to others—to make that attraction real, to affirm it as a value. In the same situation a singer’s impulse is to want to sing the song. And then he or she might go through a thousand doubts and cavils over a minute or five decades: Can I? What if I fail, and dishonor the song? Am I ready? Maybe I should wait, wait til I understand it better, have more to give it, than I do now?

I think if Bruce had sung, I’d he’d recorded the Commodores’ ‘Nightshift’ or the Four Tops’ ‘7 Rooms of Gloom’ in 1983 or even 2003 they might have seemed like novelties, cute tributes: Hey, wouldn’t it to be cool to do this? I think what you might hear on the ‘Only the Strong Survive’ album is very different: just as the Beatles and The Rolling Stones wanted to introduce Americans to their own culture, to Motown and Chuck Berry and the blues, to present those forms as bedrock, and maybe even add to them, to make a mark on them, to join them like Paleolithic people in Australia or France adding their handprints to a cave wall where other hands had left their marks a hundred generations before, so that by the time the cave closed up or was abandoned and purposely sealed ten thousand years after it was first occupied it would carry its whole history on that wall, just as, in Springsteen’s hands now, the songs, reaching some people now for the first time, are not nostalgia, not curios, but living history, as in truth the so-called oldies of 1959 or 1969, on the ‘Oldies But Goodies’ albums collecting songs that were five or three years old, as if that was a lifetime, as pop careers of one-but wonders in those days it was, always were.

So no, I don’t think by singing these old soul songs now the singer in question wants to be anyone. I think he wants to sing the songs.

The Killer did "Rockin' Pneumonia" on Young Blood--a very underrated album where even more of the material is interesting.

Thanks for the concise comment about Dion. Bingo.

Glad you're doing better and FOLK MUSIC is a better Dylan book than Dylan's Dylan book!

Bruce's soul album is comparable to the Stones’ Blue and Lonesome, I think, something between a self-indulgent goof and an educational homage. I like Bruce well enough (as a musician, not sure about his Obama stuff) but prefer the Stones (as musicians, not sure about Mick and his ballerina). Both were, in a sense, fakes all along and I don’t care. The Stones invented themselves and essentially a culture and ain’t stopped yet; personally I enjoyed their cover album, reminded me of their first (I’m old enough to remember that release). Bruce sang about driving as if he really could and would and did drive across country like Cassady, which he confessed on Broadway was not precisely the case. Well, not at all the case. But loving the soul music, that was clearly real all along and it comes through on the recording.