Ask Greil: December 5, 2023

Having missed most of the Golden Age of Top 40 (I was born in 1965), I'm fond of listening to Dave Hoeffel's weekly countdowns from the 1960s on SiriusXM to get a sense of what pop radio was like then.

I know it wasn't always golden. The most recent countdown he did was from Dec. 7, 1963. "Dominique" at No. 1. "Sugar Shack" (which you single out in your Beatles essay) at No. 6. Johnny Tillotson, Jack Jones, mediocre Neil Sedaka... alongside, admittedly, Beach Boys and Dion and Motown and even "I'm Leaving It All Up to You," which I think of fondly partly because its bored guitar solo reminds me of the hilarious one in the Bonzo Dog Band's "Canyons of Your Mind."

How did you get through it before that Beatles jolt of energy? What stations did you listen to, and what were the DJs like?

(And yeah, I know there was always something, even after the Beatles. I can't imagine hearing "The Ballad of the Green Berets" several times a day.) —TODD LEOPOLD

Those were terrible years for people who lived on the radio, as I did. There was Motown, and the occasional far left field What IS That? like Jimmy Soul’s (sure, right, whatever) “If You Wanna Be Happy,” but the morass was so killing I found myself spending most of my time away from Top 40 and over at KSFO, to a nightfly DJ obsessed with how all of American culture was turning ‘beige’ and played standards when he wasn’t talking. That’s when I learned something about Frank Sinatra, and treasure to this day his album No One Cares and the perfect expansion of “I Can’t Get Started with You.” KPFA was playing “Please Please Me” and “There’s a Place” (by the Beetles? From England? Like Acker Bilk?) in the spring of 1963 in the Bay Area, and while they were thrills they didn’t connect outside of themselves.

With the appearance of the Beatles on Ed Sullivan there truly was a sea change, an instant explosion. The day after, if not the same night, there was a new spring in people’s step, a new energy, an urge to go out and find yourself and the world. I’m not sure if they excavated a new zeitgeist waiting to breathe or if they were their own zeitgeist the world attached itself to. As new songs and new hits tumbled out of the radio there was a sense of anticipation that ruled the day.

Martha and the Vandellas’ 1963 “Heat Wave” was probably a better record than anything the Beatles or the Rolling Stones released in the US in 1964 (they would have been the first to say so) but it seemed to exist in its own world that you were privileged to see. It didn’t seem to make its own new world that you could live in, and the Beatles did. (Motown didn’t remake the map of the country until just later, with the chart takeover of the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, and the Miracles’ “The Love I Saw in You Was Just a Mirage,” which was better than “I Can’t Get Started with You”). It was completely right that Robert Christgau called his great piece on the Beatles’ end “Living without the Beatles”— for what seemed like a generation, with a few years feeling like a whole, lived lifetime, people did live in a world they and the Beatles had made together. It wasn’t a dream that could be declared over. It was a world that, for a thousand reasons, all captured at the end of 1969 in “Gimmie Shelter,” had shifted on its axis. Keith Richards said he wrote the song on a stormy day, but as the song finished itself, it brought a greater storm into view.

It's apparent that there's a real friendship and admiration between you and Dave Marsh; I remember the piece you co-wrote with him that ran in the Michigan Voice in 1984 about voting for Mondale. But it seems to me there's been a fundamental disagreement between you two about music and art, and that you've been covertly arguing about it through your writings for 30 years or so—Marsh being the Puritan, also the Utilitarian, and you being the Art for Art's Sake proponent. Am I imagining this? Are the disagreements only a small ratio compared to what you agree on? Or are the disagreements more matters of taste rather than philosophy—he doesn't seem to be an admirer of Robbie Robertson, you don't laud Pete Seeger, etc. —ANDY CALLIS

Critics who agree about everything aren't critics. You could go so far as to say that people who agree about everything aren't people. It's true there are fundamental divides in what we value, allegiances we might have, but some of it involves going into matters that one or the other of us might not want discussed—I'm speaking politically, not personally. I can maybe put it this way: Dave was one of two colleagues who were disappointed and angry that I had written Lipstick Traces after Mystery Train. They thought, in the age of Reagan, that it was a betrayal, turning my back on America to run around with a bunch of European art snobs. I've said many times that they weren't wrong—not that I would trade the nine years it took to write that book for anything. Let's just say that where Dave and I went in separate directions it was never about trivialities, and I don't believe it ever damaged our friendship.

I don't remember the Mondale piece at all.

—> Just a clarification on the Dave Marsh question—I read his essay on Kurt Cobain's suicide and "Puritanical" isn't the right word for Dave's rock'n'roll outlook; "Moralist" might come closer—I think you used that term to describe how he appears in the Creem doc. —ANDY

Yes. And for Dave moralism is a cultivated stance. A long, introspective, political reflection on the questions of right, wrong, decency, cruelty, racism and its refusal, and what one can reasonably be expected to do about them: enough, too little, nothing, worse than nothing.

I remember you telling another commenter to stay away from Howard Zinn when they asked you for advice about a class on American history they were teaching. What are your views on Howard Zinn? And how do you believe the subject of history should be approached instead of the way Zinn did so in A People’s History Of the United States? —BEN MERLISS

Howard Zinn brings to bear a lot of unknown, ignored, and suppressed material in A People’s History and other books. But the book is grounded in an end to history: that is, everything in it has to serve the one dimensional argument that is the book’s reason for being, which is to expose the perfidy of what Zinn takes as conventional or mainsteam historiography and the fatal genocidal and capitalist rot at the heart of the American story. That’s why he can’t deal with ambiguous, self-contradictory figures like Lincoln: they won’t hold still for his typography.

Dear Greil:

Hello there. I'm so glad to hear that you're feeling better. I wish you and your family the best of health.

I wanted to ask you some questions about your review of Bob Marley & The Wailers' Exodus, which ran in Rolling Stone magazine on July 14th, 1977. I recently saw a picture of a press-clipping with part of the review on it, on Pinterest, but I haven't been able to find a copy of the complete review. Do you think you could please post the full original review on one of your websites soon? I really would love to read it.

Do you still stand by what you wrote in that review? Do you still think that Exodus is a weak or compromised album? And—especially since it seems to me like so many of the songs on that album (especially "One Love" and "Three Little Birds") have become synonymous in so many (white, non-Jamaican) peoples' minds, with all of Bob Marley's music, and indeed with reggae in general—has your opinion of any particular songs from Exodus changed over the years? What do you personally think of "Three Little Birds," that's what I really want to know. But I really would love to read your full original review.

Best regards —Elizabeth Hann.

Here's the original Exodus review, from Rolling Stone, July 14, 1977:

There is a contradiction here between the enormous abilities of the Wailers — particularly the magnificent rhythm section of Aston Barrett, bass, and Carlton Barrett, drums, and the spidery lead guitar of Julian “Junior” Marvin — and the flatness of the material Bob Marley has given them to work with. The more I listen to this album, the more I am seduced by the playing of the band; at the same time, the connection I want to make with the music is subverted by overly familiar lyric themes unredeemed by wit or color, and by the absence of emotion in Marley’s voice. There are some well-crafted lines here, but given Marley’s singing, they don’t come across. The precise intelligence one hears in every note of music cannot make up for its lack of drama, and that lack is Marley’s.

This is very odd. From the time the Wailers’ first American album, Catch a Fire, was released here, it was drama that carried the Wailers’ music across the water and made it matter to people who had never heard of reggae, and who may well have had to look up Jamaica on a map to figure out exactly where it was. “Concrete Jungle” was as dramatic as Muddy Waters’ “Rollin’ Stone”; “I Shot the Sheriff” was a one-act play that crossed the boards in under five minutes. On the Wailers’ disappointing last album, Rastaman Vibration, there was still “War,” where Marley summoned up visions of eternal conflict merely by chanting excerpts from a speech by Haile Selassie. For that matter, Bob Marley onstage defines the kind of drama that grows naturally out of the music of a people who refuse to accept their native land as their true home, whose music, again and again, points them toward the temporally impossible but mystically necessary goal of a return to Africa. As with the overwhelming “Jah Guide” on ex-Wailer Peter Tosh’s exciting new album, Equal Rights, Marley onstage is ominous, determined, full of barely suppressed violence. At the same time he offers a suggestion of warmth, of unshakable confidence, of an invitation to the audience to follow him on a heroic quest.

Exodus doesn’t reach these heights, nor does it seem to aim for them, save on the seven-minute title performance, which sounds like War on a slow day and wears out long before it is half over. If I didn’t have more faith in Marley I’d think he was trying to go disco — the tune is that mechanical. The four songs on the first side that lead up to “Exodus” — songs of religious politics — are all well made, but within the most narrow limits; the best of them is “Natural Mystic,” Marley’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” (though where Dylan seemed to say the answers were blowing away, Marley is certain they are blowing straight to anyone whose soul is pure enough to receive them). On the second side the album falls apart; the mix of sex songs (on “Jamming,” Marley sometimes sounds like an obsequious nightclub singer) and tunes about keeping faith simply do not sustain one’s interest. Marley’s performance never reaches out; it seems to collapse inward. There’s no sense of the dangerous, secret messages one half heard on earlier albums; on Exodus there are no secrets to tell.

Now, I have to say that reading this is somewhat embarrassing, as re-reading so many old record reviews, mine and others', can be embarrassing. It's that the form itself is boring. Even if what's being said is somehow invigoratingly right, or rightly dissenting, it can die in its box. Obviously, I didn't know that "One Love" would go on to become a sort of anthem, or to stand in for everything the group ever did—but I should have caught on to that ambition in the song, what today we would call its attempt at self-branding, and then gone on to try to explore what was cheap and pandering in the song, in its embracing music even more than its I'll-tell-you-what-you-want-to-hear words. But I do have to mention that the review brought forth a phone call from Nik Cohn, the first music writer I admired unreservedly, who taught me so much, the only time we ever talked, with he telling me how uncomfortable the piece made him, with a white American writer telling a black Jamaican musician what to say and how. He didn't condemn me. He just wanted to say, think before you do that again.

Have you ever been to the Smithsonian Holocaust Memorial in Washington DC? Whenever I’m there I find that no matter which room I ponder things in, I am always drawn to the book shop more than any other part of the museum, because I keep thinking to myself “Which stories are the right ones to absorb and which ones are not?” And on that note: What has been your experience with Holocaust literature? —BEN MERLISS

At the museum, the wall of photos from a single exterminated village was overwhelming, but so many presentations, from films to lone documents, have the same effect.

I read Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. I saw the horrible photo “Execution of Two Ukrainian Children,” which I write about in Lipstick Traces. I read Lucy C. Dawidowicz’s The War Against the Jews. I read David Irving’s 1977 Hitler’s War—the title meant as a con, the argument being that it wasn’t Hitler’s war at all, that Hitler was forced into war by the UK and US and may not even have been aware of the the mass exterminations until it was too late to stop them. I was a book critic for Rolling Stone at the time and aware of the huge PR campaign Viking was putting behind what they were betting would be a major bestseller. The American Booksellers Association convention was in San Francisco that year. At a party I buttonholed the publisher and asked why he was publishing a Nazi—which later events have proven Irving definitively is. He got flustered and acted as if he hadn’t maybe sort of read the book as carefully as he might have. Yeah. The book received more than respectful reviews—until people began to catch on.

Yet more determinative were two events. One was visiting Dachau in 1961, before it was made over with A/V displays and guided tours. It was just an anbandoned place. The ovens looked as if they’d been turned off the week before. And years later at the Telluride Film Festival I saw the 1948 film The Last Stop, a movie about Auschwitz made by Wanda Jakubowska, who had been held there as a Communist, with a cast of Polish movie stars and villagers from the surrounding towns. Though it was not about the eradication of the Jews of Europe it made what happened real to me in a way nothing else had. It was in the art of the film and the deep warmth of Jakubowska—a month later I was able to sit down to dinner with her and though she didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak any of the six languages she did, a translator sat between us and after a few minutes he was doing such a good job we both all but forgot he was there and felt as if we were speaking directly to each other. That brought the weight of it all home in a way that other Auchswitz memoirs didn’t. There are many ways into this defining story of the 20th century—which for so many today remains an unkept promise they mean to keep: Judenfrei.

Hi Greil.

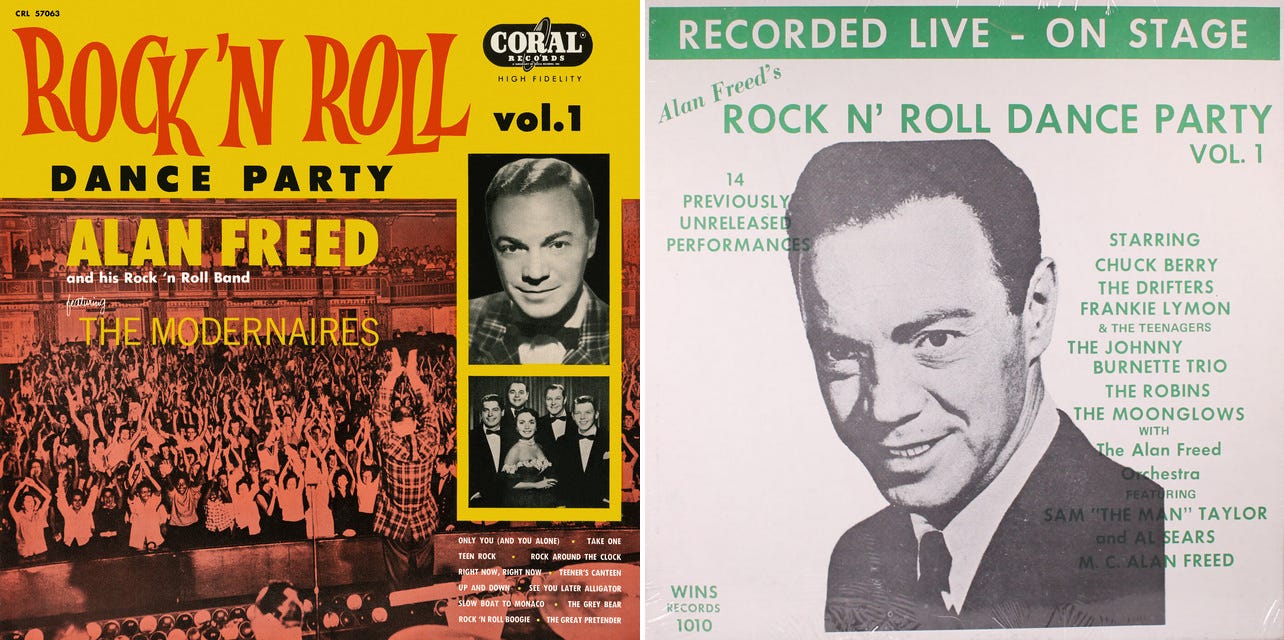

Just proposing: let's delete the 1956 Alan Freed's Rock N' Roll Dance Party Vol. 1 (Coral 1956) from your Treasure Island list, and replace this terribly stiff album (save for the big fat blues instrumental "Slow Boat to Monaco") with Alan Freed's Rock N' Roll Dance Party Vol. 1 on WINS (a label, and the name of a New York radio station where Freed hosted his Dance Parties).

The WINS album was released much later, in 1970, and features Freed himself announcing on stage a fabulous list of rock 'n' roll pioneers (on this first of four volumes notably Chuck Berry—"Maybelline" & "Roll Over Beethoven; Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers—"Why Do Fools Fall In Love"; The Drifters—"Your Promise To Be Mine" & "Ruby Baby" and The Johnny Burnette Trio—"Tear It Up"), performing before a truly fantastic audience.

Musically, many live recordings are a such a thrill. Conceptually, Alan Freed's Rock N' Roll Dance Party Vol. 1 on WINS is wild and perfect. So let's swap the two albums with the same name. Deal?

Greetings from Brussels —ARNAUD

Thanks for this. New to me. I'll look for it.

Hi Greil,

I came across this blurb on the Wikipedia entry for Abbey Road:

“Robert Christgau reported from a meeting with Greil Marcus in Berkeley that ‘opinion has shifted against the Beatles. Everyone is putting down Abbey Road.’”

Having only read glowing accolades about Abbey Road, I’m curious what the beef was with the album when it was first released.

Also, if time and space permit, I’d welcome reading your thoughts about Jonathan Richman’s oeuvre. There’s a unique, refreshing charm to his songs that’s unlike anyone else’s.

Thanks always for this very fine column. —BILLY I.

I remember that well. The album seemed jerry-built, put together out of scraps that seemed to have little to do with each other. Some of the songs were embarrassingly dumb, such as "Maxwell's Silver Hammer"—confirmed in spades some years later when I had the misfortune of seeing Jessica Mitford sing it. "Oh Darling." "Mean Mr. Mustard." "Polythene Pam." And then the huge worldwide hits "Something" and "Here Comes the Sun," which were unbearable. The only thing there that seemed to have any reason for being was "I Want You," the true colors of which Elvis Costello brought out years later in his song of the same name, which was better. And if I recall correctly the first bootlegs of Get Back were out by then, making Abbey Road look like a clean-up job in advance—of something that only suffered by being cleaned up, or having a load of dirt dumped on it, by Phil Spector when it came out as Let It Be.

I've been a fan of Jonathan Richman since first seeing him play at the Longbranch in Berkeley (there's a great album of one of his shows there). I wrote about that and the Berserkley version of "Roadrunner" in Lipstick Traces, with the excuse that the Sex Pistols had tried it in rehearsals but really because I wanted to see if I could write about it, like climbing a mountain or swimming across the San Francisco Bay. For a time he got better and better because he let his imagination run wild and seemed afraid of nothing, like sounding four years old or 60 and clueless. "Dodge Veg-e-matic" might be his best song—"I like to watch it rot"—because it's something no one else ever born would have thought to do. I listen to him on Bandcamp when an alert comes through. It's hard to think of him as 72—I'll bet he still looks 25.

Greil - Any thoughts on the ongoing "discovery" and releases/repackaging of Neil Young's 1970s material?

They've come in a variety of titles: Hitchhiker, Chrome Dreams, Homegrown, Archives II... not to mention an endless stream of live shows.

Tons of overlap... I'm not complaining, mind you. I'm a huge fan of Neil's 1970s work, and he was remarkably prolific around the time of the dissolution of his relationship with Carrie Snodgrass.

My personal favorites from this treasure trove are the live show from The Bottom Line in New York and the London motel room version of "White Line" with Robbie Robertson. —Joe O.

I haven't kept up. There's too much. I pass the sets in Ameoba Records thinking, "Maybe this one?" and then keep going. The "White Line" you sent starts off with the kind of harmonica dive—into centuries of wondering what the instrument is for, wondering how something so primitive, really pan-pipes as a different machine, can say so much, really hint at so much—that brings a flood of emotions, isolation most of all, into play, and then it... gets regular. That happens too often—he's ready to go over the cliff and then he gets in his car and drives away. Give me "Over and Over" and "Like a Hurricane" and the guitar passages in "Cowgirl in the Sand." I know there are many officially released versions that I haven't heard but probably never will, in the same way that in 1975 I found a 12-volume set of the explorer Richard Burton's illustrated and unexpurgated and probably half-made-up translation of The Arabian Nights, published by the Burton Society in the 1890s, at Moe's Books in Berkeley, and took it home with the intent of reading it all in my 90s. When we moved out of the big house where it had sat on a shelf for 38 years to a small house, I realized I was never going to read it, and took it back to Moe's, long after Moe had died, but the store was still the same. I got exactly what I'd paid for it so long before. I'm afraid if I took all the Young Archive releases home the same thing would happen, except that someone would have to take the stuff back to Amoeba after I died.

Following up on your recent comments about San Francisco, as well as an older response about “the real DiMaggio brothers”—Joe, Dom, and Vince—I wonder if you ever got a chance to see any of those real DiMaggio brothers play. I grew up in Wichita, Kansas, at a time when the western-most outpost of major league baseball was Kansas City, where the Athletics stopped briefly on their slow roll west to Oakland. Or maybe Las Vegas. At any rate, in 1959, when I was 12, my Aunt Cleo put me and my younger sister on a train to KC, and thence to Municipal Stadium, where on June 23, I saw my hero Mickey Mantle hit two home runs and a triple. To be young was very heaven, etc.

Vince DiMaggio’s career was pretty much over by the time you turned two, not that there were any major league teams near San Francisco in the 1940s. But if I remember correctly, you spent some time as a kid with your father’s family in Philadelphia. And Philadelphia had an American League team—those peripatetic A’s—up through the 1954 season. Did you ever get to Shibe Park, and happen to see Dom’s Red Sox or Joe’s Yankees?

I enjoyed rooting for the Catfish Hunter-Reggie Jackson Oakland A’s of the early ‘70s, but never got to see them in person. I did get to see Vida Blue pitch for the Giants on opening day, 1979—and nearly froze to death in Candlestick Park.

I’ll close with links to my three favorite versions of “Take Me Out To The Ballgame.” There’s the Haydn Quartet’s original 1908 version, Bruce Springstone’s 1982 version, and the hands-down winner—Jerry Lee Lewis’s epochal appearance on Shindig in 1965:

I watched in awe as a teenager, and I haven’t changed my mind since. —ROBERT MITCHELL

I went to games in Philadelphia—but only the Phillies, so I never saw the Yankees. Thanks for "Take Me Out to the Ball Game"—that 1908 version really never changed, did it? Until Jerry Lee got his hands on it. I could see him playing ball as a kid but can't imagine him ever attending a game—it wouldn't be about him! You can catch the way he changes "If they don't win it's a shame" to "if I don't win." And really, while Shindig gave you a chance to see all kinds of people that never would have made it on TV without it, as a show it was unbearable. I almost never watched it. I couldn't stand all the go-go dancers—and here there seem to be about a hundred—they might as well have dumped a ton of confetti on the performers while they were trying to play. And Little Neil with his little piano on top of Jerry Lee's piano—it takes a sick mind to dream that up. Why not zoom it in so he's singing out of Jerry Lee's pocket, like a twin cojoined at the hip?

I did see the Alou brothers. When Filipe Alou arrived people would rhapsodize about the magical assonance of his name, the way it skipped off the tongue was a ski jump. After Reggie Jackson retired and opened a vintage car emporium with a great soul jukebox in Berkeley, I had the luck of spotting him in a 7-11 at about 5 AM. I welcomed him back and drove off to the airport feeling blessed. The only comparable experience was taking two friends new to the Bay Area to a favorite trattoria in San Francisco, telling them what a great place it was even if few people knew about it, and having Clint Eastwood stroll past our table.

Greetings!

Some time in the 1990s, I was speaking with a young Irish gentlemen who'd come to the USA to find work. He made this comment about a co-worker of his who was difficult to get along with: "He's been a regular antichrist this morning!"

Which I thought was an unusual comment. I asked him about it, and he said that language was used back in Dublin to comment on, for example, a small child who'd spent the morning crying, shouting, and generally making his or her parents miserable: "Yes, Seamus was a regular antichrist this morning."

Yes, my friend said, Irish people might sometimes call a tantrum-prone child an antichrist. And I thought that since they say "an antichrist," there must be more than one in their philosophy.

Which, of course, made me think of your book Lipstick Traces, in which you pointed out Johnny Rotten/John Lydon's referring to himself as "AN antichrist" in the popular hit "Anarchy in the UK." Again, the phrase implies that there is more than one.

Now, since the singer's parents were from Ireland, do you suppose that he might have been echoing that phrase, rather than claiming to be what some (?) Christians say will the enemy of Christians during the last days, as described in the book of John the Revelator?

If he were, it might have been kind of funny, in my opinion.

Thank you for your time. (Hey, and for all those great books and articles too.) —JOHN F. CALLAGHAN

That usage is new to me. It clarifies what, as is your focus, is a true question: it’s traditional in the annals of heresy for people to proclaim themselves ‘the Antichrist’ (and far more often for people in positions of authority to proclaim others as ‘the’ Antichrist), but whoever before said he was an ‘an’? It’s like an insane person, or a cult leader, proclaiming himself or herself ‘a Jesus Christ’ instead of, necessarily, if they’re going to get any money out of it, ‘Jesus Christ.’

Maybe what matters, though, is that the sulfuric opening of ‘Anarchy in the UK’ is big enough, sufficiently frightening, to sport a ‘the’ rather than the ‘an.’ Maybe so much so that for anyone who really takes the song in, the ‘an’ dissolves and ‘the’ appears in its place. But on the other hand, maybe it’s a considered or instinctual grant of freedom, pure DIY: If I can be an Antichrist, so can you!

In the upcoming Leonard Bernstein biopic Maestro, Bradley Cooper wears a prosthetic nose in order to portray the legendary composer/orchestra conductor. Already this has elicited much anger and charges of anti-semitism. I don't know how to feel myself, knowing full well that actors down through the ages have worn false noses (obviously, anyone portraying Cyrano wore one and Orson Welles always tinkered with his looks onstage/before the camera). However, I've seen the trailer for Maestro and I can't avoid staring at Cooper's nose. I think the movie has been ruined for me. Now, I dread what Timothée Chalamet might do in his impending film portrayal of Bob Dylan! —JAMES R STACHO

From stills I've seen from the forthcoming movie, it seems to me the problem is that Bradley Cooper's nose is bigger than Leonard Bernstein's ever was. That's what can throw anyone off. Whether or not Cooper can act his way past that is another story. I'd bet he can, but we'll see. Still, it goes back to my feeling, after seeing The President's Analyst way back when, that Geoffrey Cambridge should be cast in all movie roles, starting with Freud. Of course, he's not available at the moment. Today? Maybe Lady Gaga or Cate Blanchett. As for Timothée Chalamet, seeing him on SNL last Saturday, he's got that angular facial bone structure of Dylan in 1966 down completely. If the people running the show have any sense they’ll go with that and leave the rest alone.

You once said you stopped watching HBO’s The Wire halfway through season two, because you didn’t care what happened to any of the characters by then. Why was this? What was it about the characters (or their arcs) that turned you off The Wire? —BEN MERLISS

The people on The Wire, cops and criminals and everyone in between, seemed like tired, unthinking shells for ideas they were supposed to represent. In Homicide and Boyz n the Hood and Menace II Society you didn’t know what anyone would do next, but you could sense the people at issue trying to figure it out. I didn’t see anyone thinking on The Wire so after a season and half I turned it off. I‘ve since developed a serous distaste for Dominic West by way of The Affair and The Crown which I stuck with because of the female characters and actresses.

If you can believe I’m not looking for a list, which books on Abraham Lincoln have left the deepest impression on you? —BEN MERLISS

Oh, no? How else to respond?

Lord Charnwood, Abraham Lincoln (1916)

John Ford, Young Mr. Lincoln (1939)

Edmund Wilson, “Abraham Lincoln: The Union as Religious Mysticism” in Patriotic Gore (1962—a year later, President Kennedy honored Wilson at the White House and awarded him the Medal of Freedom, and during pleasantries asked Wilson what the book was about, which is to say he did not actually honor Wilson at all).

Michael T. Gilmore, “1858: The Lincoln-Douglas Debates,” in A New Literary History of America, ed. GM and Werner Sollors (2009—originally, in 2006, we asked the the recently elected U.S. Senator Barack Obama to write this entry . His representative quickly got back to us and said the senator was too busy preparing to run for president to take it on. He had been in office less than two years. “President of what?” we asked.

Get Back could have been even worse:

Also, what did you think of “Now and Then”? I watched the video and thought "Beatles porn..." Maybe that sums up Get Back as well? Thanks

I wrote about the song in my recent Real Life Rock column [here]. But I won't get as close as "Beatles porn."

And the cartoon says all too much about Peter Jackson.

Sept. 1963, beginning of 9th grade, my parents uprooted the family to a place not far from where we grew up but where the social stratification was oppressive, unlike anything I had experienced. I spent a lot of time after school listening to the radio, and fall 1963 (after Little Stevie Wonder's "Fingerprints Pt. 2" sustained me for the summer), I particularly remember the amiable "Sugar Shack" as the best thing on the radio/Intercom my mom had installed in the new house. But "Sugar Shack" was burning out, and so I kept the radio/Intercom low. The first time I heard "I Wanna Hold Your Hand," it was low background, but I felt a consciousness shift. The next time I heard it, I ran to that damn radio and turned the volume full blast. As close as a depressed 14 year old could come to a born-again experience. It was like "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" the next day in school: Everybody looked the same, but were different.

"And then the huge worldwide hits "Something" and "Here Comes the Sun," which were unbearable." - Thank you, I thought there was something wrong with me for hating both of these. For that matter, hating most of "Abbey Road."