One of the reasons I first became attracted to your writing is your obvious love for Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry. You responded to a question recently regarding when you first heard Music From Big Pink and you spoke of how quickly the music grabbed you and how big an event it was in San Francisco and indeed throughout the country.

While Roxy Music in 1972 was a pretty big deal from the get-go in Britain, they were only well known in small pockets in the US at that time (especially in Cleveland and Detroit, interestingly enough) and were largely under the radar, even in the music press. When did you first hear Roxy and which song got your attention right away? As a young, established rock journalist at the time, did you find yourself trying to turn other critics and writers on to Roxy? Were you ever mystified that they weren't a bigger deal here in the US?

Speaking of Ferry and Roxy, I think the haunting and gorgeous “When She Walks In the Room,” from The Bride Stripped Bare, is perhaps Ferry's finest solo effort. But I find the album lacking compared to its predecessor In Your Mind (which sounds more like a Roxy album, in a good way). For me, Bride marks the beginning of Ferry's search for that idealized Avalon overproduced sound that he'd focus on for the following decades. Yet I find myself playing the album frequently since that one song is so majestic and towering and worth the whole album. Which of your favorite songs by an artist or group that you love and are important to you stand alone on albums that are otherwise dull or disappointing or that you flat out don't like? —TIM JOYCE

The first two Roxy Music albums made no impression on me, if I was even aware of them, and they’re still not part of the band’s cosmology for me. It was Stranded that made me a lifelong fan of the group and Bryan Ferry (and for that matter Andy Mackay—I still have his 45 cover of the Rebels’ “Wild Weekend,” a song that is Roxy DNA). Probably it was the album jacket that got me playing it. I was swept away first by the way Phil Manzanera cracks open “Amazona,” then by the wonderfully pandering would-be money grab of their Eurovision entry “A Song for Europe,” finally by “Street Life” and the way they titled the album after a word in the last line of the song—and the idea in that word.

“Love Me Madly Again” may be the Ferry number I play most, for the sliding rhythms in the instrumental passages , and nothing else on In Your Mind still rings a bell for me, so I suppose that’s a one-track album for me, but so what? That one never-seems-to-end number makes it better than a hundred other albums I care about. I like everything on The Bride Stripped Bare. “Can’t Let Go,” which never does let go, and for its mention of the bedroom suburb Canoga Park. The glorious covers, “That’s How Strong My Love Is,” especially. “Carrickfergus.”

Once in the Pompidou in Paris I saw Ferry’s art history professor Richard Hamilton at a dada exhibition. I went over and asked him if he didn’t think Roxy Music should be playing in the galleries. “The Bride Stripped Bare,” he said.

Greil: The descriptions of the power and other worldliness of Anne Briggs and Karen Dalton singing live in the “Jim Jones” chapter of Folk Music reminded me of a piece of old film collected by the Irish Traditional Music Archive.

The archive collects Irish traditional music and song in all forms—written, oral, tapes, etc. and its director put together a series of programmes for Irish television called Come West Along the Road.

The piece I am referring to is filmed in a pub in Kerry in the West of Ireland and is of an older man singing a love song in Irish called “That District Where She Lives.” The note says the recording is from 1967 but it could easily be 1927. There is nothing in the context to suggest a date. There are only men in the pub and their clothes could be from a much earlier time.

However from my point of view the extraordinary thing is that not only does the singer keep his eyes closed but another man holds his hand right through the song. I have never seen anything like that before and I have heard many singers in many pubs.

(The piece starts at 45:46.) —JAMES CASEY

That truly is a performance unlike any I have ever seen. I wonder if Van Morrison ever saw it, and if it left him inspired or shamed, promising himself at least for a moment he never deserved to sing again. You’re right about how it looks as if it could be so many years earlier than it was—though there’s one person in the background, with glasses, who looks distinctly less working class and far more 1967 than the rest.

The strange dance between the hand of the singer and the hand of the man, holding a half full glass in the other, who’s winding it up comes across to me as more ritual than happenstance—something the singer needs and depends on—though the hand holder does look at least twice as drunk as anyone else pictured. For that matter he looks as if he’s been drunk without cease for twenty years. Really, though, watching, I didn’t believe the song was going to end.

I'm curious to know any thoughts you have about the early work of Thomas Farber, beyond your "Undercover" review of Who Wrote the Book of Love? Am I right that he wrote as "Beelzebub" for the SF Express-Times? Some of those pieces are recognizable from Farber's first book, Tales For the Son of My Unborn Child: Berkeley 1966-69, which I read some years ago and haven't forgotten. As observation it was so specific yet so abstract, and so richly, cryptically written that it took me a long time to finish because I wanted to experience each sentence. How did that writing look to you in 1968, when the ink was still wet, and then in 1971, when the book came out, after so much had changed? —DEVIN MCKINNEY

I don't think I knew Beelzebub was Tom Farber when we were sharing pages in the San Francisco Express-Times. I met him later in Berkeley, about the time Tales for the Son of My Unborn Child came out. The title always made me think of Jonah Who Will be 25 in the Year 2000—and where is Jonah now? Who is Jonah now?

Tom was around, I was around, we became friendly, corresponded, shared writing, and when Who Wrote the Book of Love? appeared—I'm going to pass up a chance to write about a book called that, whatever it is?—I couldn't wait to review it in my Undercover column in Rolling Stone. It hit me hard. As the book of love it was a book of unsolvable mysteries.

This was after Tom got out of prison. He had become a major dope dealer. He was sent to Leavenworth and then from place to place. He wrote a distanced, damaged book about it: Tales for My Brothers' Keepers, under the name of Thomas Flynn, published by Norton in 1976. One story from it I've often thought about: a fellow inmate, African-American, reads about a book called The Power of Blackness. He loves the title and thinking it's about black power orders it. It arrives: the literary critic Harry Levin's study of Melville, Poe, and Hawthorne. Which could have spoken to him.

Tom appears as Merrit Parkway III in the late Sandy Darlington's 1971 fictional-when-he-wants-it-to-be memoir Buzz River Letters (you could find it on eBay)—Sandy too was sharing pages with Beelzebub. Here is a passage:

Merrit phoned. His trial has happened. Before a judge. According to Merrit, he almost got off. The strain of posing as an innocent kid has been hard on him. At the end, he went to see his lawyer one day all dressed up in hip clothes. Of course the lawyer knew that Merrit had been "guilty" all along. But the judge didn't and was about to let him off. He leaned over his bench and looked down at Merrit and said,

"I only want you to tell me one thing. Promise me you'll never do it again."

Merrit was outraged at having to talk to the judge or promise anything. He told me that he'd paid that lawyer a lot of money so that the lawyer would deal with the judge and he, Merrit, wouldn't have to say anything. But, he says, he the lawyer tricked him.

Anyway, when the judge asked him the question, Merrit wouldn't answer.

"Like Billy Budd," he said, "I couldn't speak."

Tom was a presence. Tall, bald, usually with a watch cap, smiling. The last time I saw him we ran into each other on a subway from the airport into New York. His whole life, then, he said, was salsa dancing. I just looked at his website: he's written many more books, except for the 1980 Hazards of the Human Heart none of which I knew about, the most recent Acting My Age, in 2021. I see that he most recently taught English at Cal two years ago, but we haven't seen each other here or there. But "Acting My Age"—he'll be 80 this year, and I'll be reading him.

Been meaning to ask this for years, and possibly you’ve already written about it:

Do you think Dylan name-checked Leo DiCaprio in Tempest by way of thanking Jack Dawson for saying “when you got nothin’, you got nothin’ to lose” in the poker scene? —DEREK MURPHY

No reason to think you aren’t right, but to me it was less payback than admiration for a poor boy long way from home role well played. Especially when Jack slips away: an indelible death scene with only body language, no face in play.

Hi Greil — So nice to see a mention of Mark Shipper in the most recent "Ask Greil." I LOVED Paperback Writer—when I bought it (in the original Sunridge Press paperback edition, with your blurb on the back cover!) I was young and credulous enough to believe that much of it was true. (I actually wondered why I'd never seen their album, We're Gonna Change the Face of Rock 'n' Roll Forever, though at least I was aware enough to know that David Bowie hadn't died and they hadn't reunited to tour under Peter Frampton.)

Years later, I tried to line up an interview with Shipper, and somehow was able to leave a message with him. He called me back but wasn't interested.

That was more than 20 years ago. Have you been in touch with him at all? The only references I can find online either reference Paperback Writer or something he did called "The Shipper Report," though he does have a page on RocksBackPages.com, which links to material he wrote up to 2013. —Best, TODD

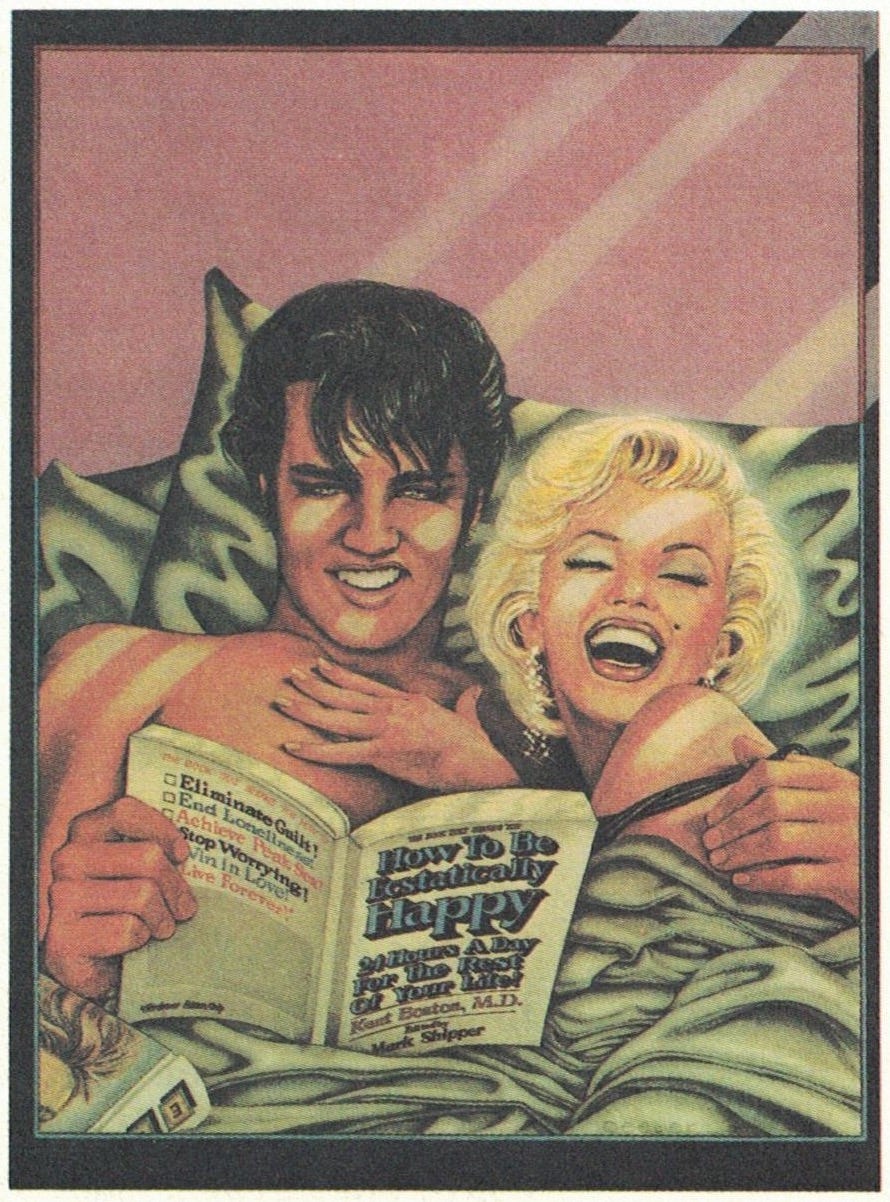

I haven't been in touch with Mark Shipper in forever. I still have his follow up to Paperback Writer, the self-help satire, which actually sustains itself, How to Be Ecstatically Happy 24 Hours a Day for the Rest of Your Life, which has Elvis and Marilyn in bed together reading the book on the cover. I have some copies of his fanzine Flash. But I know nothing. Devin McKinney went down this rabbit hole ten years ago and came up empty—see “Paperback” Trail; or, The Hunt for Mark Shipper”—but beyond that it’s all fantasy.

Hi Greil — In 2010 David Byrne and Fatboy Slim collaborated on Here Lies Love, a disco concept album about Imelda Marcos*, the Filipino beauty queen turned First Lady to the despotic Ferdinand Marcos. The album focuses on her rise from poverty to opulence under ever-present American imperialism, until the people rose up and peacefully ousted them in the EDSA Revolution. It avoids the most obvious cliches (no mention of the infamous shoe collection) and largely tells the story through the perspective of Imelda and the various women in her life, embodied in a rotating cast of mostly female singers (Florence Welch, Sia, Cyndi Lauper, etc.). The rare exception (other than Byrne himself, who sings one or two songs) is none other than Steve Earle.

While I know (and agree) full well with your frequent exasperation whenever Earle pops up for another dull and pious guest appearance, I think this is the one case where he was utilized perfectly. His turn comes on “A Perfect Hand,” described in the notes as a “song sung by Ferdinand Marcos, the handsome and ambitious young senator from the wild northern province of Ilocos. As a senator in Manila, he spots Imelda on a magazine cover where she is featured as Miss Manila, and the gears begin to turn.” Knowing she belongs to an influential family that can give him connections where at present he has none, he woos her during a whirlwind 11-day courtship, promising to lift the country up into a new Golden Age with her by his side.

While the song has the anthemic quality of an idealistic political reformer's promises, Earle cuts across this, delivering his tearjerking promises and smarmy praises of “the ladies” in the wily voice of his old snake oil salesmen character from “Copperhead Road,” supported on backing vocals by his then-wife Alison Moorer (as if Imelda is echoing these promises to herself, simultaneously seeing through this consummate politician’s bullshit and allowing herself to be seduced by it).

Imelda Marcos (who is still alive) has been photographed listening to this album. One wonders what goes through her head while doing so. Regret? Entitlement? Or just a smug satisfaction at outliving her old enabler Henry Kissinger?

*I know, this sounds like one of most random Mad-Libs ever. —JAMES L.

I wish I could agree with you. I don’t harbor Steve Earle ill will as I do other people in the music penumbra. I think he’s usually completely believable and scary playing backwoods villains in the movies. But I always detested the Byrne-Fatboy album—it struck me at the time and still does as colonialist in a reverse double switch, as David Thomas might put it—defining any attempt to erase Spanish-US rule as fundamentally noble—and that’s all I can hear in Earle’s voice here. Plus—why would bringing up the shoe business be a cheap shot? It went to the heart of it all. And they didn’t have a track of Imelda singing her favorite song. Not hard to guess: “Feelings.”

Hi, Greil. It strikes me that the Kinks single, "Where Have All the Good Times Gone" is a direct riposte to "Yesterday" by the Beatles, issued three months earlier. Things happened fast, even back then.

Compare "Yesterday/love was such an easy game to play" with "Yesterday was such an easy game for you to play." To my ear that line is Ray issuing a well-warranted dig at the McCartney tune, and more broadly taunting the Beatles about the miseries of their suffocating fame. And there might be some jealousy in the mix...

Anyway, I'm curious what you think. Thanks! —CHRISTOPHER JAMES HESLER

That never occurred to me because I never really heard that record. With Ray Davies there was a thin line between a jaded eye and plain sourness and sourness was all I got out of this.

He was world class complainer. That led to some of his best work, “I’m Not Like Everybody Else,” “The Way Love Used to Be,” “Sunny Afternoon,” and reams of his worst, from The Village Green album and all of the Lola album after the title song and on and on. It had nothing to do with his finest moment, “Waterloo Sunset,” where a lonely man who can live only vicariously let anyone feel love. He could have complained that no one cared about him, that no one even saw him. But that’s what he wanted, and that was his paradise.

January 2024 marks the 50th anniversary of Bob Dylan's return to touring as he and The Band played 40 or so dates in North America in early 1974. They opened at the Chicago Stadium and I remember the newspapers featuring a lot of Dylan content in their weekend arts sections the prior weekend. As a 13-year old not knowing a lot about Dylan, I wondered why he rated as highly as The Beatles, whom I worshipped or even the Rolling Stones. When I listened to Dylan's mid-60's albums, I became converted. But back to Tour '74: were you there that first night? Because the weird thing about that opening night was that Bob remained onstage during The Band's songs which probably resulted in a distraction for the audience and for the five members of the Band because I have to assume, Dylan didn't know Robbie Robertson's songs as well as he did his own. By the second night, the show changed to what it remained until the end of the tour: Dylan plays only his songs either w/The Band or solo and the Band plays their songs w/o Bob chiming in on rhythm guitar/harmonica. It also gave the audience three separate ovations for Dylan (start of the show; start of his solo set; return w/Band for the final set) because as you well know, Bob Dylan was worshipped by his fans at that time. Hope Sony will eventually do a box set of the tour like they did w/'66 Live. —JAMES R STACHO

I never heard about that, and it sounds so—off. Unless he was playing rhythm and singing on the choruses, he’s off to the side playing the doting and judgmental father, even if Garth Hudson and Levon Helm were older than he was and they and Robbie Robertson had recorded professionally before he did?

In the late ‘60s, a very cultish music magazine called Fusion continually promoted the idea that Dylan had written all the songs on Music from Big Pink, especially “The Weight.” Let’s hope Dylan didn’t read that.

A recent conversation with a friend about Bogart's trajectory from cheap hood to romantic hero led me to re-watch a Bette Davis movie—1937's Marked Woman in which Bogey has only a supporting role as a soft-hearted DA. This is dime novel melodrama as high art and the movie is not the kind of thing to watch just before bedtime—the fate of Davis and her gin joint comrades is too harrowing. So with my brain still buzzing the memory of another marked woman suddenly came to mind, a well-known journalist who had a breakdown on national tv a few years ago when she was asked to comment on one of Trump's various sexual assaults. The subject brought up painful memories of her own and she didn't hide it, bless her. That memory was, god knows why, followed by my own memory of John Lennon singing "She's not a girl who misses much..." “Happiness is a Warm Gun” is one of those Beatle songs that seems to be made up of spare parts, and it jumps through so many hoops it's easy to forget he starts the song as an ode to one particular woman. Then it goes off the rails pretty quickly with "hob nail boots" and eating soap before getting to his real point; he needs a fix because he's going down. And because it's personal for John too, bless him, and he can't hide it either, the "bang bang, shoot shoot" is just as harrowing as Davis's acting and that journalist's real-life trauma. You remarked (in The Rolling Stone History of Rock and Roll) that, with some of the songs on the White Album, John "seemed to be getting closer to the essentials of his soul." I wonder, does the White Album still take up space in your head? The songs, certainly John's, seem to pop up at the oddest times in mine. —CHARLIE LARGENT

There’s a lot from that album that has stuck, hard. This was a bad time for John Lennon, which he’s defiantly embracing, living in heroin with Yoko, whose affirmation that they were taking it as a celebration of themselves as artists should not be forgotten. There’s so much that’s desperate, sick, lashing out, so many times when they’re giving you more than you thought you were buying: “Helter Skelter,” which was scary long before Charles Manson grafted himself on to it, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” which really does sound as if the singer wants to shoot somebody, and rub the gun against his body if not someone else’s, which goes down to the depths, for me, with the soap verse, which combines Nazi concentration camp imagery with coprophilia, and especially on what has always been the most surprising and ineradicable performance on the record, “Yer Blues.” Yes, for “Feel so suicidal, just like Dylan’s Mr. Jones,” yes, as Jann Wenner said at the time, because it put almost all the British blues bands to shame, because the Beatles could do what they did so much better, but most of all for that out of nowhere rhythmic whiplash that ends it, a second that makes it feel as if for a last word the singer is erasing himself.

I’d bet “She’s not a girl who misses much” is a line John was carrying around, waiting for the right song to use it.

What are your views on Eddie Cantor? —BEN MERLISS

He was on TV a lot when I was a kid, but I remember nothing about him. Like Milton Berle he went back to the Jewish blackface minstrel tradition. Look at Michael Rogin’s Blackface, White Noise for the whole story.

In your Ralph Gleason obituary you wrote: "Last year when I finished a book [Mystery Train] and gave Ralph the manuscript to read, he responded with a long letter correcting my errors, worrying about possible limits on the book’s audience, comparing it to an obscure novel he and I treasured and then proceeded to go out of his way to do everything he could think of to make the book a success." This came up on a greilmarcus.net comment section some time ago, with a few people (myself included) wondering what the "obscure novel" might be. My stab-in-the-dark guess was Mumbo Jumbo, but someone questioned just how "obscure" that really was (also nothing that they, anyway, saw little resemblance between the two books). This is something you wrote almost 50 years ago, but do you recall now what the book was and how, in Gleason's mind, it compared to Mystery Train? —SCOTT WOODS

My memory is anything but perfect, but this was instant: Italo Svevo’s 1923 Confessions of Zeno, about a man, his psychoanalyst, and quitting smoking. Apparently now called Zeno’s Conscience. It’s a version of Zeno’s paradox about Achilles and the tortoise, the epitome of postwar European modernism, and both utterly pleasurable and torturously frustrating to read.

Juxtaposition, noted:

"The Mekons can say anything, and do nothing; Chuck Norris and Sylvester Stallone can say nothing, and do anything."

—from your piece on the Mekons (and USA Combat Heroes) at Artforum, reprinted in Ranters & Crowd Pleasers aka In the Fascist Bathroom.

"I couldn't manage to make myself nasty or, for that matter, friendly, crooked, or honest, a hero or an insect. Now I'm living out my life in a corner, trying to console myself with the stupid, useless excuse that an intelligent man cannot turn himself into anything, that only a fool can make anything he wants out of himself."

—from Dostoyevsky's Notes From Underground, 1961 edition translated by Andrew R. MacAndrew

Not saying the latter inspired the former, but I'm curious what you make of the match. I tried searching your name plus "Dostoyevsky" but could only conclude that you'd read The Grand Inquisitor (I haven't). Has he inspired you in any significant way?— Best, A.

I read a lot of Constance Garnett translations of Dostoyevsky in high school and college and later versions in the years after. If that passage from Notes from the Underground were in the back of my mind when I was writing about the Mekons and USA Combat Heroes, it was way, way back. What stayed with me from Dostoyevsky most strongly is Zosima's rotting corpse in The Brothers Karamozov and the line in The Grand Inquisitor about people cast so deeply into hell—"those God forgets." I found the contradiction of the idea of an all-knowing god who is capable of forgetting completely terrifying.

I remember so well writing that piece. It was picking up that magazine at a drug store and just being torn apart by the idea that anyone could write and publish such bile, presenting a third-rate actor as a real life real world actor—it was as terrifying as the idea that God could forget. The thing was like a magnet of evil in my hand. And it presented a country that was real, with Chuck Norris and Sylvester Stallone pictured in exactly the same superman imagery that people now apply to Donald Trump, and with absolute seriousness.

It spoke so clearly to the isolation of the Mekons, of myself, of anyone I cared about at that time. It was someone being invited to a potluck, bringing a big pot of boiling dog shit, putting it down with all the other dishes, and everybody says it's the best dogshit they've ever had, can I get the recipe?

Hi Greil - More proof that Dada is, indeed, everywhere.

Climate change headline from the ski-slopes in today’s London Independent: “Temperatures Too High Even for Fake Snow”

—MARTIN MAW

You lost me there.

Do you think The Beatles 1964 song “Baby's In Black” (Beatles For Sale LP) was directly influenced by the 1958 country hit “Long Black Veil”? Both songs have a similar lyric content (“Oh Dear/What can I do/Baby's In Black/And I'm feelin' blue”) juxtaposed with (“She walks these hills/In a Long Black Veil/She visits my grave/Where the night winds wail”) and both have an easy chord structure when played in G major, the Beatles adding a soaring bridge to their C&W pastiche. It would have taken a little more digging to know “Long Black Veil” during Beatlemania, but Joan Baez did travel with them during a tour, so maybe they learned it from her. A few years later, “Long Black Veil” seemed to be everywhere with famous covers of it by Johnny Cash and The Band both appearing in 1968. John Fogerty has said CCR did their own version, but didn't release it because The Band beat them to it. I'd like to think John and Paul knew country music well enough as fans of Carl Perkins and Buck Owens that the connection between the two songs makes sense. —JAMES R STACHO

I'd like to think the Beatles were more influenced by Truffaut's The Bride Wore Black, but that didn't come out until four years later. Or maybe vice versa. I don't hear any relationship between "Long Black Veil," which is so classically structured it felt much older than it was when it first appeared, and "Baby's in Black," which for me never goes anywhere and is one of their more forgettable songs.

Hi Greil - You've indicated in past posts that you are a fan of Ray Donovan. I am as well and have often felt it was a somewhat unappreciated show. No one really wrote about it and even dismissed as a show that only "old people watched" (a joke in Netflix's Grace and Frankie—itself a show about "older people.") That's a shame. While it had stellar acting and writing, as to be expected in this era of so-called prestige TV, it probably featured some of the best directing on any TV show since The Sopranos. The show had its weak points of course. Sometimes it was plot heavy with threads that didn't really lead to much but that didn't bother me too much because I often don't care about plot in film, TV or books.

Characters like Mickey Donovan (the best geriatric gangster since Junior Soprano) or Ray's brothers, the has-been ex-boxer Terry and eternally troubled Bunchy had a level of gravitas that elevated them from their pulpy clichés. And as for Ray, he was a golem. Seemingly lifeless and molded to seize or repay whatever debt his latest master instructed him to do. A man whose soul has been calloused a long time ago.

Much of this has to do with Liev Schreiber's brilliant performance, on par with James Gandolfini as Tony. True, Tony was equal parts charm and repulsion and you saw all facets of Gandolfini's range when he played him. Ray, on the other hand, is far more stoic and quite often has little dialogue throughout many episodes. This is no less compelling, however, as Schreiber often wore his emotions on his face and how he carried his hulking body (like Gandolfini) and he returned a sort of visual physicality now seemingly forgotten in acting. It's cinematic if anything and Ray Donovan at its best reached those heights.

I'd love to hear your own thoughts on this show since it's already seemingly entering a memory hole admidst our glut prestige TV and streaming options. I care less about where Ray Donovan ranks with the great TV shows and more of how it holds its own with the very best of noir and hard-boiled fiction and even surrealist literature/film. Did you find the film finale satisfying? I personally did but some seemed to feel it felt short (I actually thought the previous season finale also worked as a series finale). Thanks! —ANTHONY VOLPE

For me the high point of the series was Embeth Davidtz’s role as an art dealer front for Russian mobsters and, as a breast cancer survivor with one reconstructed breast, seducing Donovan in a plot so dense it was hard to escape, for the viewer no less than the character. There was daring in the idea and the staging that no good show has since had the nerve to even try to match.

Given that I spent the entire show waiting for Mickey to be crushed by a falling tree hit by a car accidentally tripped by one of his idiot sons—since Jon Voight came out as a right-wing troll I’ve found it impossible to watch him in anything—my problem, not his—the ending came too late.

How does he fit into LA noir? From Chandler’s “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean” to “Down these mean streets a man must go who is meaner still, who doesn’t care where they began or where they end.” Show cancelled and wrapped up? I was never really there at all. Except when Embeth came on the set.

Greil and I have certain artists in common e.g. Dylan, The Band, but have different tastes on specific songs. He hates Gates of Eden whereas I like it. He dismisses Endless Highway while I enjoy it. I play and have played music live for people and so experience the sensation of making a song come alive via guitar or keyboards, but Greil comes at it from, I assume, a purely academic listening perspective. And to play Long Black Veil and Baby's In Black back to back is fun for a musician and it makes perfect sense to me that they share some tangential relationship. As for The Kinks Where Have All The Good Times Gone, I have read that is more about their loss of innocence v. any commentary on The Beatles' Yesterday. For commentary on The Beatles by Ray Davies, look up his published review of Revolver in 1966. Ray is very critical of certain songs, likes others, admires few. But I love his work and again Greil, dismisses some great Kinks albums: VGPS and Lola v. Powerman and The Moneygoround. Those are top Kinks records in their high prime. Great band, great songwriter. Lastly, I'm surprised he didn't know about the stage snafu on Dylan/The Band's Tour '74 during the opening night. It's an interesting curiosity that Bob was playing Band songs onstage for a set. It was also probably a disaster as Dylan did not know those songs well enough, I presume, to play them along with The Band. They quickly changed tactics the next night as I described and the rest is recorded history.

Another excellent set of conversations, thanks. Thanks also to James Stacho for finding a link between ‘Long Black Veil’ and ‘Baby’s in Black’, which is there lyrically if not intentionally. I’ve never heard it as a Beatles country song, but a strange Beatles blues. Last year, jazz pianist Brad Mehldau included the song on his stunning LP of solo interpretations of Beatles songs, ‘Your Mother Should Know’. On first listen, ‘Baby’s in Black’ is the hardest to recognise: he has slowed it down, and uses broad chords with heavy cadences. He’s turned it into a *gospel* song. https://youtu.be/0lmfpP5Oh2c?si=C6DrQ6FtYKCJZH6a