Ask Greil: November 10, 2023

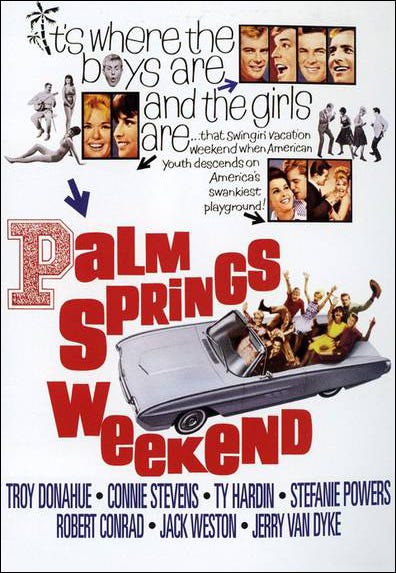

Not a question, just a comment. Some TCM programming from the other night made me think of you immediately. They devoted the evening to films with "Weekend" in the title, much as, soon after the last election, they had a night of films with "Joe" in the title. Just after midnight, back-to-back, they had Godard's Weekend followed by Palm Springs Weekend, with Troy Donahue and Connie Stevens (and with Troy Donahue on the soundtrack). "Real Life Top 10 material, for sure," I thought. —ALAN VINT

Someone at TCM has a great sense of humor. And realizes the TCM vault holds more treasures than Sean Connery found in The Man Who Would Be King.

I may have morbidity on the brain, but my first thought reading the names you mention was, and who's still alive? Connie Stevens!

I'm a native San Franciscan, I'm wondering what was it like for you to grow up here and how did it shape your thinking and style? —ROBIN K. CHANG

Simply put, I think being from San Francisco gave me an unearned but priceless sense of superiority and invulnerability. I came from and was part of the best place on earth. It had a storied history and I was part of it. It never left me and though I live across the Bay in terms of self worth and self belief I’ve never left.

My mother was born in San Francisco. Her mother was born in Portland but lived her adult life in San Francisco and nowhere else. My mother’s father was born in Honolulu but was in San Francisco during the earthquake—as was my adoptive father’s father—and served as a marshal patrolling the streets to stop looters. My mother’s mother’s grandparents came to San Francisco from Germany in 1856. Their sons Abraham Lincoln Louisson and Henry Clay Louisson were born there before the family left for Hawaii where their daughters Lahela and Belle, both of whom I knew well, were born in 1865 and 1870. My grandfather was a San Francisco architect who worked on the Palace of Fine Arts and other landmarks that were pointed out to me as I grew up.

I lived with my mother and her parents in San Francisco until 1948, when my mother remarried. We lived in a flat across the street. In 1950, with my by then two siblings, we moved to Palo Alto and then in 1955 to Menlo Park. San Francisco was always the City, a special, historical-mythical place. We got dressed up to go there—just to go there, not for any special occasion. My father was a San Francisco attorney—going to his office in a tall downtown building made me feel as if I was at the heart of the city. Throughout my childhood I took the train to visit my grandmother, a joyously imperial woman who seemed to know everyone in town, from shopkeepers to famous restaurateurs. She took me to traveling Broadway shows, to see Harry Belafonte in theaters and the Kingston Trio in North Beach nightclubs. And reading Herb Caen’s column in the paper every day was part of this too—the sense that San Francisco was the coolest city in the world, always was and always would be.

So I came of age with a huge case of San Francisco snobbery toward the rest of the country and as big chip on my shoulder when I made the shocking discovery that people from the east thought California was a backward place and that New York was the center of the universe. I knew what Barry Goldwater meant when he said he wished the Eastern seaboard would break off and float out to sea. Throughout college and after I got sick and disgusted and angry over people saying, “But you’re from New York, aren’t you?”—unable to believe that anybody Jewish and reasonably intelligent could be from California.

Today it isn’t real to me, it’s a violation of legacy and history, that so much of downtown San Francisco has become an open sewer of human wreckage, of filth and crime, of self loathing and disrespect. My father used to walk me down Skid Row toward the train station and explain to me what it was and how people got there. He could never have imagined that that one street, genteel compared to the ruined parts of San Francisco today, would become the face of the city.

The city I knew is still with me in every word I write. So what’s your story? How did it shape you?

Hi, Greil, hope you’re well and doing better. I have your new Dylan book but have not yet read it; years ago I bought Mystery Train and years ago I lost it, unread. I’ve read In the Fascist Bathroom, The History of Rock n Roll in Ten Songs, and The Doors. I was born in 1977; I got into the Doors right around the time of the movie. Had a few studio albums and loved their greatest hits, the red one, and played it over and over until, I guess, Nirvana, not too much after that, fall of 1991. For years I could no longer hear them, nor did I want to. I started gradually to come around, read your book when it was published, and have thought for a while that they were one of the most deeply weird bands of all time, especially given their popularity. They seemed totally outside of everything, at least from my b. 1977 vantage point. I often think of a documentary clip I saw a couple of years ago, can’t remember the title, where Jim is surrounded by either fans or concertgoers or just a crowd. He knows he’s on camera. People start playing with his hair, maybe pulling stuff out of it or trying to pull out an actual hair. He gives the camera a look, not really playing to it, but not really amused by the crowd. Just a strange kind of half-smile. What he really thinks is unclear to me but contradicts the stereotype. But it was early on, I guess. I apologize if you wrote about this clip and I’ve forgotten.

I love one of Robert Christgau’s reviews, although I don’t agree with the beginning Jimbo stuff. The last two sentences are: “His three sidemen rocked almost as good as the Stones. Without him they were nothing.” So, after all this… beyond the obviousness of singing and writing lyrics, what does a frontman do? I also use Jim as I know that you don’t listen as much to, say, James Brown or George Clinton. Thank you and take care. —RICHARD SCHULTE

My sense, especially from John Densmore’s Riders on the Storm, is that whatever his, Robbie’s, and Manzarek’s flair and inventiveness as musicians, they knew Morrison was different—not just handsome, not a poet, but different from anyone they’d ever met or ever would. With him, impossible as it might have been at any time, they were in a place they could never reach on their own. And the same was true for Morrison.

They all stood out as individuals and as members of the group. In the Doors, they weren’t the other guys. We found them thrilling. No matter how many times I heard “Light My Fire” in 1967—a hundred times at home, hundreds and hundreds on the radio, ten times or more live—and maybe a thousand times in the years since—I never got tired of it. I still hear new things in it. The first album is one of the strongest and most joyous—the joy of people discovering their own lives and the joy of realizing that you might have discovered, at least for the moment, the voice of your own time—of a year or two of shockingly great albums. It’s as good as Aftermath and better than the first Velvet Underground. I just listened to the original Brecht-Weil “Alabama Song,” in German and English, as used in the soundtrack for Harry Smith’s New York film Mahagonny—the Doors version could have dropped right in: I’ll bet Brecht and Weil would have loved it and I’d bet money Lotte Lenya and Fassbinder had their own copies of The Doors and maybe Strange Days too. “The Crystal Ship” is ineffable—even if I can never quite get by the clumsiness of “being filled,” through I don’t know what the better verb or construction would be. “The End” lives up to its absurd ambitions. And after a year it was a race with time to see if they could keep up with their time and if you could keep up with them. Then they became an embarrassing Top 40 band and made embarrassing albums. And then with their last two LPs there was a different story, some encounter with their own entropy and the discovery that a tougher voice, a tougher look at life, was within their grasp. Their music contained Manson, COUNTELPRO, the Ron Karenga-Huey Newton war, and the murder of Fred Hampton before the fact and after it.

I liked the Doors. Their failure meant a lot to me and so does the staying power of their music. Could anyone have replaced Jim Morrison? Sure. The other one. But nobody else.

Can you expand on the circumstances that found you at one of Swift’s Eras concerts? Besides “The Man” and “All Too Well” were there any other highlights or impressions? How did it compare to other stadium shows you have seen? Is this tour of any cultural significance? —ANDREW MACDONALD

I wasn’t there to see TS in Chicago. Our younger daughter took her 15- and 12 year-olds, who both pronounced it the best day of their lives. I watched their videos. It was thrilling.

I can’t recall a memorable outdoor stadium show other than the Beatles (and the Ronettes) at Candlestick Park in 1966. I can imagine shows working at the Giants’ current jewel box in San Francisco. 3,000 is about the limit for shows that stayed with me. So many club shows I remember as if I were still there.

When someone calls Steely Dan "lounge music" or "dad rock" or whatever—besides rolling my eyes at the cliché; you can bet they sneer at "Hotel California" too—I always think, "Have you listened to the lyrics?" No one slides from the particular to the general, or vice versa, like the Dan: "We can go out driving on Slow Hand Row / We could stay inside and play games, I don't know"; "They got a name for the winners in the world / I want a name when I lose / They call Alabama the Crimson Tide / Call me Deacon Blues." And what particulars: "that fearsome excavation on Magnolia Boulevard"; "When the dawn patrol got to tell you twice / They're gonna do it with a shotgun"; "the Wolverine up to Annandale." And no one else, besides maybe Warren Zevon, would think to summon the wonder evoked by prehistoric cave drawings by marveling that they were produced "when there wasn't even any Hollywood." I don't know a single poet who doesn't love Steely Dan. —MICHAEL ROBBINS

When Jim Miller was finishing The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, there was a discussion over including short entries on new performers who might be enacting the future of the music. Steely Dan was one. And right, even if the real future they were acting out was one no other performers could enter.

Hi, Greil: boygenius. Yea or nay? —RICHARD RAFFEL

As the Go-Gos would likely have been too kind to say, they don’t have the beat. Any beat. And less than nothing to take its place.

Not a question, but Ty Cobb’s mother shot and killed his father

From Wikipedia:

On August 8, 1905, Cobb's mother, Amanda, fatally shot his father, William, with a pistol that William had purchased for her. Court records indicate that William Cobb had suspected Amanda of infidelity and was sneaking past his own bedroom window to catch her in the act. She saw the silhouette of what she presumed to be an intruder and, acting in self-defense, shot and killed her husband. Amanda Cobb was charged with murder and released on a $7,000 recognizance bond. She was acquitted on March 31, 1906. Ty Cobb later attributed his ferocious play to his late father, saying, "I did it for my father. He never got to see me play ... but I knew he was watching me, and I never let him down."

—ANDY CALLIS

I forgot that. Probably wouldn’t help anybody

Jann Wenner, asked and answered, certainly. Still, I clicked on this sitdown with Phil Spector (not included in Wenner's new book; we can guess why) and found myself transfixed. Dylan as opera, Elvis as limitless; some concept of 13-year-old whores as "hipper" than previous. I felt like I was reading a man from Planet X—although the Dylan criticism was and is a common one. (Ditto his remarks about Motown.)

And I have no proof, but I'm presuming he saw the "pit session" from Elvis' comeback special, so he's comparing it unfavorably to those more formal performances from same.

Any memories of this one from when it came out? Any thoughts on it now? —ANDREW

Jann’s interview with Phil Spector was one of his best, and one of the best Rolling Stone published. After his producing career dried up, Spector had been lecturing at college campuses on the nature and absurdity of the music business, telling outrageous and true stories about his life from the Teddy Bears to his present-day electrified fence. He was ready to talk and Jann offered up what to Spector were naive questions which brought out hilarious candor in response.

If anyone was a philosopher of rock & roll, he was it. No one thought more seriously about what it was, what it was for, and what it could do—on the premise that it was something authentically new, a thing in itself. See also Nik Cohn’s chapter on Spector in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, edited by Jim Miller.

I’ve listened to Hackney Diamonds all the way through two times now and I’m afraid I have to admit that both times I found myself helpless against its onslaught. Admittedly Mick Jagger has only one subject these days—the emotional toll of a life spent pursuing supermodels. However, I have often thought that rock stars should write more about the reality of their daily existence. For example, instead of yet another song about a working-class guy being chewed up and spit out by the system, wouldn’t it be nice to hear Bruce Springsteen sing about something he really knows, like how difficult it is to find a parking space in downtown Rumson, New Jersey on a Saturday morning—how you often have to circle the block four or five times, and when you do finally see a vacant space, it frequently turns out to be too small for your SUV. My question though is what do you make of critics who are not content simply to state that a new album is unworthy of regard, but go on to attack the sort of person the critic thinks might like the album, in this case someone who is old, sad, pathetic, clueless, intellectually enfeebled, morally bankrupt, sexually inadequate, desperate for the reflected glow of someone else’s wealth and celebrity, and incapable of appreciating anything that isn’t familiar, shopworn, and tired? Have you noticed this too? —TIMOTHY BYRNE

Well, I hope you’re not referring to me, attacking all the morally compromised people who might like something I don’t or vice versa. Having just come from Priscilla feeling as if my IQ dropped 50 points in the course of the movie, I have nothing to say against anyone who loved it—other than critics who swooned over it, or pretended they did, or used the picture as an excuse for a self-flatteringly joining in Sofia Coppola’s so-called project of interrogating the lives and enforced roles of young women through the ages. But I’ve probably done it in the past. I think I’ve learned as a teacher to ask people what they think—so that if someone says, why did you hate that, I loved it, I’m much more interested I talking about their response than mine.

One thing I do stay away from is imputing any autobiographical content or context to anyone’s work. I don’t care about Mick Jagger’s life; I want him to make a convincing argument about life or some vagary of it. Still, speaking of Bruce Springsteen looking for a parking place—in 2000, after he took part in my American Studies seminar at Princeton, we climbed into his SUV and he started driving to New York for a party for the Kristen Ann Carr cancer foundation. We got stuck in terrible traffic. I was discombobulated. How could this be happening to BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN? Doesn’t a police escort or a special lane automatically appear when he’s experiencing some kind of difficulty, just like in the movies when the hero pulls up somewhere and there’s always and empty spot waiting? By him or me it would have made a lousy song.

Hi Greil… I’ve read several of your books and greatly appreciate your writing. I have a question about a response you gave concerning the Rolling Stones: “They made a deal with the devil: for giving up their music Mick and Keith get to live forever.” I didn’t understand the “giving up“ part. As in surrender, or as in offering up, or neither? (And totally agree with you there’s no way Ron Wood is an equal shareholder.) —WIN

Surrender. If old blues singers made a deal with the devil to play like angels, Mick and Keith made a deal to give up their music for whatever they wanted more.

Martin Scorsese has cited several of his favorite classic Hollywood films as influencing his own epic Killers of the Flower Moon. William Wyler's The Heiress stands out in the scene where Molly (Lily Gladstone) finally rejects her duplicitous husband Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio) after he has been giving her shots of insulin tainted with poison. Nothing so harsh happens in The Heiress where Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) is trying to marry wealthy spinster Katherine Sloper (Olivia DeHavilland despite her domineering father's (Ralph Richardson) vehement objections that Morris is just a fortune hunter out for her money. While not quite film noir, The Heiress is certainly noir-stained as everyone ends up psychologically and emotionally maimed in the end and loses the love of someone whose love they may have taken for granted. The verbal rapiers are deadly with Richardson wielding them early on and Olivia having the last say. Clift's character is thoroughly handsome (of course, he's Monty Clift in 1948!) and charming, but his intentions are in doubt as the eye of his affection is mousy and witless Katherine before she undergoes her amazing transformation into a woman scorned. While I appreciated the new movie, none of Scorsese's trio of characters portrayed by DeNiro (uncle), Leo (suitor) or malleable victim (Gladstone) have any of the same character arc (they remain essentially the same at the end as when we meet them) as those in The Heiress, where without any physical violence whatsoever, leaves everyone in a smoldering pile of psychic ruin at the end. Scorsese's version of the Old West has nothing on author Henry James drawing room Hell! —JAMES R STACHO

I think you’ve hit on something I plan to explore in my next column—the lack of deep feeling in so many Scorsese movies—his apparent inability to draw it out of his characters, if not himself.

Please help settle an argument between me and my spouse. I say the most heavy metal song in Dylan's catalog is "Tell Me Momma" from the 1966 "Royal Albert Hall" show. She says it's the version of "Groom's Still Waiting at the Altar" on the 1985 Biograph collection. Who's right??—JH BLOOMBERG

Let’s look at them as amusement park rides. “The Groom” is a whirligig. “Tell Me Mama” is a loop-de-loop roller coaster that while you’re on it you can’t believe will ever stop, and when it does you stumble off wobbly and confused.

Heavy metal? Black Sabbath would have given a lot for that first, huge guitar chord that opens the “Ballad of a Thin Man” those few songs after “Tell Me Mama.”

Tell Me Momma is amazing and solely exists as the opener in live '66 Dylan shows. And all honor and glory to the late, great Robbie Robertson (god, I miss him) for that shivering guitar intro on Ballad Of A Thin Man. Dylan, The Band...we will not see the likes of their talents ever again!

I visited Paris with my family during the summer, and - coincidentally - we found ourselves at Père Lachaise Cemetery on July 3, the anniversary of Jim Morrison's death. While our daughter explored the grounds on her own, my wife and I visited the resting places of the usual notables - Moliere, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Oscar Wilde, et. al. One of the last sites we visited was Morrison's grave. It was the only one guarded by police, who were likely expecting a raucous crowd given the date. But I saw more visitors paying respects to Edith Piaf. Those besides us who did visit looked closer to my age (59) if not older. Meaning kindly seniors wearing Doors t-shirts, with some looking like they just had their hair done. Time is moving much too fast.