Hi Greil, I hope all is well as it can be. Shell-shocked by the election, some folks are taking some peculiar (whatever gets you through the night) approaches to self-care. For some people, there aren't enough Bowery Boys movies, for others, it's music, and someone on Bluesky posted a Staple Singers track I'd never heard before (not a surprise, I love them but I'm not a connoisseur). It's a cover of “A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall,” and I swear I don't know what to make of it. The arrangement sounds almost jolly, like a hoedown. The Grand Ole Opry aspects are certainly on display. Any thoughts? —CHARLIE LARGENT

You know, after Altamont I couldn't listen to rock 'n' roll at all. I found my way into a little hole in the wall Berkeley record store that had a lot of collections of old country blues and spent the next year listening to nothing else. After the 2001 terrorist attacks the only thing I could listen to, and I mean the only thing, was the New Pornographers' "Letter to an Occupant": it was that leap, which I must have heard as a leap of faith. That's where I discovered Neko Case, who I'm listening to now, a show where she follows "Hold On, Hold On" with "Alone and Forsaken," because she came up on the YouTube stack next to the Staple Singers' "Hard Rain."

I didn't know it either. But that is a song to get lost in when the world seems like a desert on fire. Trump is sending a message: You have no idea how far this is going to go, or how fast. You think you're protected, that you're safe? No one is safe. Cruelty is the currency. He and his party want to make people hurt, in Congress, banishing their own members to a nowhere of unpersonhood. Don't ever forget that he left office the first time as a serial killer, with after no Federal executions for 35 years, in his last six months he had thirteen people burned.

The first time I heard "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" was just before the March on Washington in late August 1963. I was 18, about to start college at Cal. I'd just seen Bob Dylan at a Joan Baez show in a field in New Jersey, had never heard of him, didn't even catch his name, was poleaxed. So I'm at a Pete Seeger concert outdoors at Stanford in what seemed like a swamp. He sang the song with enormous sweep, drama, fervor. I'm sure he said who wrote it and what it was called, but I didn't catch that either and wouldn't have cared. It was a thing in itself, it had no reference points as it came through the night. I felt the way Dave Van Ronk described hearing it in a Village club—he didn't know what to think, he spent the night walking around, trying to get hold of what he'd heard, where he'd been, and, though he didn't say so in so many words, what it felt like to realize he and everyone he knew was being left behind, to find their own way as best they could.

What the Staple singers do is bring it down to earth, as an old song, an old story they all know by heart, a drama in which each can and must play a part. I hear them saying, this is the story we've been living all our lives, this is how it feels, up against a mountain, a quest without end, without rest.

But the best? The most dramatic? The freest?

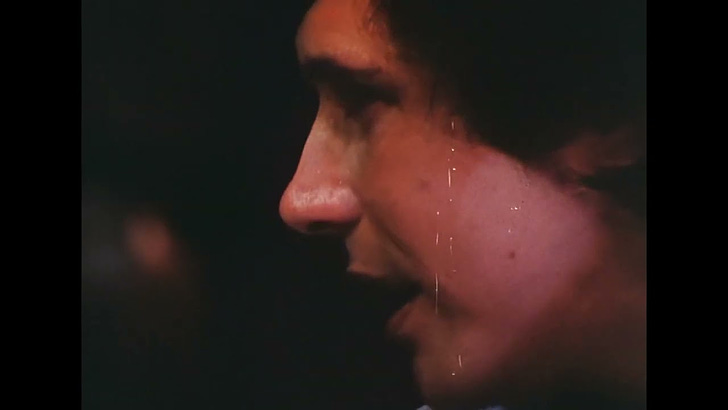

This:

I played it once for Robbie Robertson. Is this a joke? he said. Of course it is. And it's Ferry's way of getting all the way into the cave of this song—and as this, from a lifetime later might be saying, never wanting to leave:

So scanning the headlines it's clear what happened: Harris was a radical who was too moderate; she entered the race too late and her campaign went on too long; voters wanted change and pined for how things were five years ago. At least no one is saying that Biden shouldn't have dropped out, though doubtless some are thinking it.

Worse is the recent disinterment and elevation of James Carville, often by people who should know better (Ezra Klein, Maureen Dowd). There's a documentary on the horizon—one can only imagine how much heavy lifting the word "colorful" will do. To me, Carville isn't much better than his colorful counterpart Roger Stone: a sleazeball is a sleazeball whether he has a "D" or an "R" after his name. Plus, he stole Doug Kershaw's nickname.

As a Bill Clinton fanboy, what's your take on Carville?—STEVE O’NEILL

I liked James Carville for what he said about the first days of the Clinton administration, when it became clear he would have no role: after he died, he said, “I want to come back as the bond market. It seems to have all the power.” Today he is just an e mail machine. He’s not comparable to Roger Stone, who has done real damage to real people, and who will continue he to do it, and is financially corrupt to his toenails, with an automatic presidential pardon for any crimes for which he might be convicted—if Trump doesn’t ipso facto interdict any prosecutions he doesn’t like. But since he will appoint all US attorneys it’s not likely any such prosecutions would be brought.

How do you think the Beach Boys came up short as a “surf” group as opposed to a “car” group? [See “Surf Songs”] —BEN MERLISS

Their car songs are a lot more fun. The lyrics are all details, just like a kid with a car who has to make sure everything is right. Brian Wilson didn't surf, but unlike Bruce Springsteen at the same age I'm sure he drove. And the music has more punch, probably because they were having more fun themselves.

I have question about a passage in Mystery Train—my apologies if it's addressed in the upcoming edition or covered in the most recent one. In the chapter "Sly versus Superfly" you wrote:

"The Temptations, as usual, copied themselves, with the horrendous 'Ghetto' ('Hmmm, life sure is tough here in the ghetto'), and turned art into shlock in record time."

I don't recall any Temptations recordings with that title, but their follow-up single to "Papa Was a Rolling Stone" was "Masterpiece," a 14-minute slog that boasted profound lyrics such as "in the ghetto, only the strong survive." Is it safe to assume this was the shlock you referred to?

If so, you're right that the Temptations copied themselves. And it wasn't even a good copy. "Papa Was a Rolling Stone" is a work of drama—the children desperately investigate their papa, only to find they're circling a void—but "Masterpiece" is dramatically inert. The singers point out how bad life is in the ghetto ("Break-ins, folks comin' home and findin' all their possessions gone/It's an every day thing in the ghetto")...and that's it. Even the riffs are forgettable. I regard Norman Whitfield as a producer-songwriter on par with Phil Spector and Brian Wilson, but "Masterpiece" was his greatest artistic failure. To give any song that title was an act of outrageous presumption, and naming an album after it was sheer hubris.

"Masterpiece" is not even the best song on the album: the proto-disco "Law of the Land" is catchy and propulsive, though its lyrics exemplify the post-Riot trend in conservative music you diagnosed in Mystery Train. And "Plastic Man" puts the sonic tricks of "Papa" (echoey haunted house horns, darting strings, tell-tale-heart bass, metronomic percussion) to satirical use in the six-minute evisceration of a slime-trailing phony (and references the O’Jays’ “Back Stabbers"). It's practically Trump's theme song, or would be if he had any self-awareness. —IA

Thanks for this correction. I suppose I heard the song once or twice on the radio and was so put off—the way the bass notes say, "Here it is, follow-up!"—that I just assumed it was called what it was about and didn't look any further. I just listened again—the 14-minute version is impossible, but what I heard in 1973 was just the four-minute single, which really is as flat and automatic as I remembered. This comes at the right time. I'm revising the Notes & Discographies right now and the new edition will be less embarrassing for your help.

What did you think of Joe and Jill Biden's photo op with Trump a couple weeks back? I agree with peaceful transfer of power and all that (if Dems opt not to do it, the system might as well not exist), but I thought the smiling photos of the three of them were rather sickening. But maybe it's something to not go with your gut on, I don't know.

Completely unrelated: were you ever seduced, even briefly, by any seventies prog rock? In your Stranded discog you refer to Manfred Mann's 1972 LP as "progressive" (scare quotes intact), but that seems like a stretch to me, not what most people would categorize as prog (though perhaps that's your point?). But did you ever catch a few seconds of one of Steve Howe's riff in "Roundabout" and catch yourself tapping your hands on the steering wheel? Why do sixties and seventies rock critics hate prog so damn much? —TERRY

About the meeting: I couldn’t sit down with someone who had insulted my very existence and dismissed the fact that I’d ever been born, so that makes Joe Biden a bigger person than I am, something I never doubted. But I think the most telling detail was that the insult continued: invited to meet by Jill Biden, the clothes horse blew her off.

Why do people hate prog rock? Because it epitomized the worst of its time, that post-60s desert of stale ideas, idiotic new trends and catchphrases, where bad tv commercials were the great art form of the epoch. It was pretentious, claiming the world while gazing at its own navel. It was pleased with itself. It had no conviction and no doubt. It was able to vanish as if it had never been, because it hadn’t.

Of course there was Can.

I’ve heard it told that a favorite pastime of George Harrison’s was to take any given situation, ranging from personal to global, and find an applicable Bob Dylan lyric to summarize said situation. Upon learning this about Beatle George my initial reaction was, “Glad to know I’m not the only one who does this.”

When playing this parlor game of George’s, Dylan’s “Gates of Eden” is a song from which I’ve mined aplenty in recent weeks. With its wealth of Daliesque imagery and Bosch-like nightmare fodder, “Gates of Eden” is a perfect song for these imperfect times.

On the heels of the November 5 election, “There are no kings inside the gates of Eden” serves as a grim reminder of how far we’ve strayed from Paradise. I can think of few lines to better describe the opportunistic likes of Vance, Musk, RFK Jr., Ramaswamy and Gabbard who’ve ridden their way to remorseless power “side saddle on the Golden Calf” as they sell what tiny souls they may have ever had. As all of this transpires amidst a barrage of pundits and conspiracy theorists sane-washing the absurd, the line “and the princess and the prince discuss what’s real and what is not” forms a relentless echo inside my head.

If these simultaneously timeless and timely lines from “Gates of Eden” were not enough, the song rides the crest of a wave whose melody is as ominous and foreboding as “Blind Willie McTell” or “All Along the Watchtower,” reminiscent of a deadly palace court where jesters are fast falling from favor. I’ve long considered this song the not-so-distant sibling of “Desolation Row.” Along with canned goods, bottled water and sacks of grains, “Gates of Eden” is a song I’d want amongst my provisions when the time comes to move underground.

In a 1974 review of Dylan’s 1974 Oakland concert with The Band, you write “‘Gates of Eden,’ which was ridiculous in 1965 and still is.”

Hoping to find the root of your dismissal of this song as “ridiculous,” I embarked on an internet search of your name and “Gates of Eden,” hoping it might shed some light on all of this. The best I could come up with was an anecdote of an overly earnest mother imploring her 10 year old child to “listen to the words” prior to Dylan launching into the song at a 1965 Berkeley concert. Really? This was a profound and pivotal enough experience to ruin this song for life for you? And, a half century later, is “ridiculous” still the word you use when speaking of “Gates of Eden”?

Thanks always for this luminous column. —BILLY INNES, San Francisco

I don't ever want to stop anyone from taking pleasure, or wisdom, or anything else from a song they like. I just say what I think and try to figure out why. That woman telling her kid to listen to the words didn't ruin the song for me, it simply (or perfectly) confirmed what I'd already heard. As I think I've said before in this forum, to me the song is horribly overblown and unrelievedly, self-consciously profound—one thing you won't find inside the Gates of Eden is humor.

Can you name a few non-musician poets who remind you of Leonard Cohen? And a few non-musician poets who remind you of Randy Newman? —BEN MERLISS

I'm sure there are a lot of people out there imitating (they'd sat paying homage to) Leonard Cohen. But since I can't bear Leonard Cohen I wouldn't know who they are.

Randy Newman? Frank O'Hara.

Hi Greil: I know you’ve been getting a lot of questions about the election. Here’s a question about the election, Bob Dylan, and your Folk Music book.

More than any other music I’ve been listening to after the election, I can’t stop listening to Dylan’s “Ain’t Talkin’.” It’s like taking a long walk to think and clear my head. The calm opening chords reminiscent of “Summer Breeze” a feint before feeling like “Someone hit me from behind.” Imagining practicing democracy as “a faith that’s been long abandoned.” Thinking about the Statue of Liberty as “that gal” that so many voters “left behind.” Worrying that for our country “the gardener is gone.”

Now, interpreting Dylan lyrics is a game as old as Dylan’s career. But reading Folk Music and thinking about the rise of the folk boom in the shadows of horrors like segregation and the the Cuban Missile Crisis, I wondered, would it be even possible to have such a connection between music and politics and an audience again in our current political reality.

I know Punk was a great “No!” to the bleakness of 1970s USA and U.K. But in retrospect, while reading your book, the Folk Boom and all the artists, old and young that it brought forward, seems a so much more unified “No!” to what was seen as the Establishment.

My questions: Could something like that ever happen again? Even given the breakup of the old system of Artist-Record Company-Radio-Listener/Buyer—and an even more-fractured audience (not bad things by the way)—could some sort of mass movement related to politics and music exist to argue truth to power exist again?

Would it even be helpful, and not just another cog in the entertainment machine?

Just some thoughts as I try to get out of my miserable brain, walking through the cities of the plague with a toothache in my heel.

Cheers to you. And thanks always for all your writing. —JEFF

Of all the questions about music I've been asked in my life, from the time I first started publishing pieces about music, in 1968, this is the question I've been asked the most. In essence, Where have all the protest singers gone—which really meant, where has the audience gone, the people who were moved by songs to see the world differently, to refuse it, to try to change it, to resist its satisfactions and comforts for something more, something better? As far back as 1971, David Bowie, not known for waving the banners of social change, was asking in his "Song for Bob Dylan" for him to come back and change the world again, to make it right, to, please, sing a protest song again.

Dylan was eloquent in his Chronicles, Vol. 1 (I hate writing that full title, since there clearly is never going to be a Volume 2, but I kind of think that was the point, or the joke—there never was going to be) about what it took for him to write the songs that put him on the map, that redrew the map. "You have to have power and dominion over the spirits," he said, to write anything as dimensional as "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" or even "With God on Our Side"—the planets, yours and history's, have to align. You have to align them. And then, after that moment, they will no longer align, and the language they produced will come out clichéd and stale, and even if it doesn't people will no longer be able to hear it. As a statement against bigotry, if that's how you hear it, there's too long a distance between "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" and "Short People."

You're right: "Ain't Talkin'" is the one. I knew from the moment I first heard it that it would be a cloud following me for the rest of my life, a conundrum that would never come to rest. I wrote a whole long chapter about it in Folk Music in 2021, after many tries before, and while it felt as if I was able to live in the world of the song, there still are lines that I've never quite caught, turns of phrase that still carry new meanings. In a way I think that Graeme Buckley, in his YouTube collage "'Ain't Talkin'—A Tribute to the Western"—where he takes clips of closeups from dozens of westerns to orchestrate the song, or vice versa—it could have been called "A Tribute to the Western--"Ain't Talkin,'" as if the song itself were a tribute to the western, which, though reaching back thousands of years to the Black Sea, it clearly is—captured the song more fully than anyone else has. It's a journey. It's dangerous. You will meet people whose faces you can't read. Almost no one will tell you the truth. You're not interpreting the song with your references to democracy and a faith long abandoned, you're hearing it, and hearing how open Dylan left all of its metaphors and elisions, so that it could speak in many ways for a long time.

Could this happen again? No, and it shouldn't. I don't want good-hearted small-minded people telling me what to think or, just as bad, that I'm right to think as I do. The uprising, the mass movement, the great refusal that you want is, as you already know, present in single songs as you or anyone might hear them. And some of them will travel, be forgotten, be rediscovered, long after we're gone.

Hello, Greil! this is wonderful. so good just to hear your voice (sic). love/ Joyce

I knew you weren’t a Leonard Cohen fan. Neither am I, but I actually was wondering if there was at least one well regarded poet who turned you off in a similar way.

On a different note I have my own take of a Bob Dylan song that seems to reflect this current time surprisingly well but it isn’t Gates Of Eden which I feel similarly about with you. My choice is It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) which is also on my shortlist of favorite Dylan songs.