A podcast produced by Yale University Press with myself and David Thomson, focusing on my book What Nails It, part of Yale’s Why I Write series, can be heard here.

So, what’s it all going to come down to on November 5? —ANONYMOUS, U.S.A.

What I wrote recently for the website First of the Month:

Two predictions: whoever wins, in the Electoral College it will not be close, and it won’t be Kamala. If she loses it will to an uninterpretable degree be because she was, from her debate with that thug through interviews into her Anderson Cooper audience session, unwilling or unable to answer a question with a straight answer, or often any answer at all. Her preparation has been unfathomable. The campaign may have ended when she was asked on The View, which is to say asked by her friends, if as president she would do anything differently from the Biden administration, and said “Nothing comes to mind” as if she were not a thinking person, but an overpaid flack, instead of saying, as anyone should have for such an inevitable, easy, meaningful question, “Of course. All administrations make mistakes. Real leaders, unlike those who call treasonous solicitations of bribery perfect, admit that. We should have done this earlier. We should have done more of that. There were institutions that needed protections they haven’t received, such as—and I will make sure that gets done”—and so on.

People noticed. They were bothered. I was bothered. It’s something that could have been corrected, and instead—as if it were a strategy—it was compounded. If, on election night, she is asked, “Why did you lose?” The same smokescreen will go up, and not a word will be remembered.

I’m not wrong about what I’m saying about how Kamala responds to questions. I hope I’m wrong about everything else. We have to be freed from this terrible family.

Hi Greil, Thanks again for all the great writing you do here and elsewhere. Two questions on the same subject:

1. You've written introductions to various books, including some that rank with your very best work (your introduction to the Stanley Booth Stones book, for instance), but as far as I know, no one has ever written an introduction to one of your books. At least not a first printing of an American edition. Is there any particular reason for that?

2. You've also blurbed (hate the word) dozens of books over the years, and I've always been a little suspect of that practise. But only because I read some writer ages ago admit that they blurbed a book they'd only read a fraction of. Maybe they wanted to help the person out or just see their own name on another book—it wasn't clear. Is blurbing as dirty a business as I sometimes suspect? How does it work anyway, are you blurbing a finished copy of a book, are you in touch with the author beforehand? —TERRY

I’ve often taken being asked to write an introduction to a book (usually for a paperback edition or a reissue) as a humbling honor and a true challenge, really a dare I’m setting for myself. Can I add something to the context of the book that was, maybe, evident when it first appeared, but now, with a later edition, no longer speaks? Can I capture and in an immediate way translate the spirit and language of a book that will open it for readers who may have only vaguely heard of it? With a reissue of Stanley Booth’s book on the Rolling Stones’ 1969 American tour ending with the Altamont show, which did not appear in its first edition until 15 years later, I wanted to focus on Stanley’s style, so rooted in Raymond Chandler and Flannery O’Connor, and reanimate the spirit of the times in which the book was witnessed, as opposed to when it finally saw the light of day. Most recently I was asked by Tenement Press to write an afterword to Lucy Sante’s Six Sermons for Bob Dylan, a little book collecting the full, original pieces she’d written for the actor Michael Shannon to deliver in a dramatization for the DVD part of Dylan’s Trouble No More bootleg series Gospel years box set. I wouldn’t have thought of saying no: Lucy is an old comrade. In the early 1980s when I was starting research for Lipstick Traces, she sent me an obscure lettrist film publication that turned out to be a crucial archive and signpost.

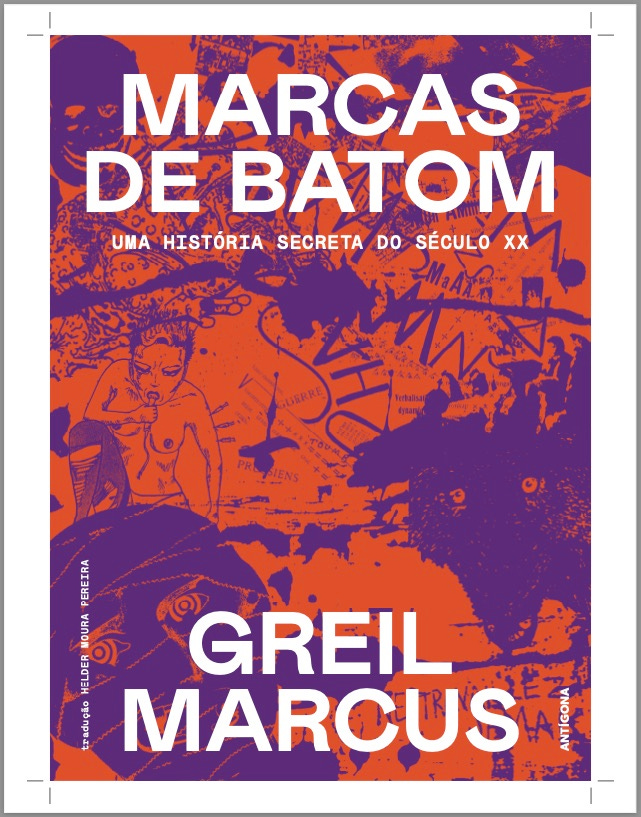

For my own books, as they first appeared there never seemed a need—it was my job to open the book. With Lipstick Traces, so serpentine, with lines written and planted so that an image or an idea or an historical fact that might only barely register on page 23 was meant to go off like a bomb when it’s echoed or in a different setting three hundred pages later, it seemed that any attempt to introduce it, by me or anyone else, would be to make it flat and simple: just dive in. When people would ask me what it was about I developed a number of one-sentence answers, but really, I’d say, and it was true, that I had to write the book to try to answer that question. And then once, at a reading at an English language bookstore in Paris—the now gone The Village Voice—the owner introduced the book so lucidly, with such poetry and flair, that I asked her if she had notes, or if someone had recorded it, so I could reconstruct it and use it as an introduction if I ever had the chance. But it was just her reading it and in a sense presenting her own dramatization which was then lost to the night. There have been many editions since—the next, Marcas de Batom, with a fabulous cover, in Portuguese, from Antigona late this year or early next year—and I’ve never not missed it. (Nicky Wire of the Manic Street Preachers wrote an introduction to the 2011 Faber & Faber edition in the UK that took nothing away from the book.) For later editions I’ve added a page noting the deaths of people who play a part in the story since the book was first published in 1989—a list that of course needs constant updating. But for the 50th anniversary edition of Mystery Train, which will come out next fall, I did want someone to create a context for it, one I couldn’t or wouldn’t—I wanted someone to read the book in a few pages of their own—so that book, finally, will have a preface.

Blurbs are a different story. I know many writers who absolutely refuse to do them, either out of some muddy moral position (Richard Powers won’t even sign books; he refused to sign my copy of A New Literary History of America, which I coedited, and where he was the only writer who both contributed a chapter and was the subject of another, which I wrote, which many other contributors had signed), or because they’re quite famous and if they did one everyone would be asking, and how do you tell one friend they’re not as deserving as another? But that hasn’t stopped Stephen King or Joyce Carol Oates or for that matter Bob Dylan. For me, I can hardly demure—too busy, don’t do them, not my territory—when my publishers have asked so many people, a lot of them people I know, on my behalf. So I do a lot. For people I know and those I don’t. Recently I was sent the manuscript of a novel about Jimmie Rodgers by someone I’d never heard of asking for a quote. That was an easy out: read a couple of chapters and say ‘not for me.’ But it was blazing with imagination, never flagged, and I was thrilled at the chance to do anything to help it. The same for Jon Savage’s new book, already published in the UK, forthcoming here, The Secret Public, about the interplay between pop music and gay liberation—though Jon is a longtime dear friend.

They can get out of hand. I was once asked to give a ride to a woman I didn’t know to an event we were both attending. I did. Not long after I received an email from her asking if I’d write a blurb for her upcoming wedding. What? “If you want a wedding to remember, don’t miss Susie and John’s! And be sure to check out their website!” I didn’t, but I wouldn’t have minded seeing who might have fallen for that con.

I very much enjoyed your interview with David Thomson, after listening to which I have an absurdly trivial, but to me vital, question: what gin do you like? —CHUCK

Beefeater.

Dear Mr Marcus:

On page 8 of What Nails It you mention you were shown the location of Stag Lee Shelton's incident with the hat. You said you "took twigs from a bush in the landscaping."

I'm wondering what your plans for those twigs were—were you thinking of them as cuttings, and trying to transplant them to have a bush nearby that could remind you of that hat?

Thank you —MICHAEL WINTER

The idea of cutting and grafting is wonderful, but it never occurred to me. It was just a—I think the right word isn’t souvenir but keepsake. They were green; soon after I got them home they turned dried blood brown. I still have them and look at them all the time.

Greil:

1. I'm wondering if Siouxsie and the Banshees ever meant anything to you. For me, their Peel Sessions is as prickly and mysterious and compelling as anything by the Slits, the Raincoats, or Kleenex/Liliput

2. Not a question, just a comment. I've been thinking about your comment, a few months back, that "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight" and "Down Along the Cove" belong on Nashville Skyline. One thing that has always struck me about John Wesley Harding is how the album moves, so naturally, from some of the bleakest and most hopeless songs Dylan ever wrote to some of the sunniest and least troubled. "As I Went Out One Morning" may be the strangest and most frightening song in his catalog, as unsettling to me as any horror movie, and every attempt to "explain" what it means has always seemed to reduce it—and I feel similarly about Clinton Heylin’s attempts, in one of his books, to figure out which St. Augustine Dylan was really singing about. "She meant to do me harm" always chills me. And while Hendrix's version of "All Along the Watchtower" has understandably eclipsed the quiet, spare original, I find Dylan's version infinitely more ominous—I believe in the existence of the remote desert castle, the two riders approaching, in his song in a way I don't in Hendrix's. But the sweetness of those final songs is just as real. The contradiction there is part of the deep mystery of John Wesley Harding, and it's why it remains my desert island Dylan album, the one I can't imagine ever leaving behind. — JUSTYN DILLINGHAM

Siouxsie didn’t register with me. Maybe it was the attitude, maybe it was the swastika, maybe it was the psychedelia in the music. But I didn’t like Billy Idol’s sneer, which he must have spent weeks looking at in the mirror until that lip came up as if being pulled by a sky hook, and he made great records that swept me away—I will never forget hearing a long remix of “White Wedding” one day driving from Berkeley to Oakland at the end of a long day and being convinced it was the greatest thing I’d ever heard. I could never get it to come across that way again. But I always think it will.

You are saying more about John Wesley Harding than most people who have ever written about it—about “All Along the Watchtower,” especially “As I Went out One Morning.” What if that had been the last song on the album? After all that had come before it—“I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine,” “Dear Landlord,” “I Pity the Poor Immigrant”—you could get to the end and just cut your throat. Or try to get rid of the thing, put it in the trash, leave it at the door of a synagogue like an abandoned baby, and find out you couldn’t.

The secret of that record? The hidden speech murmuring behind each phrase, each shift in emphasis and emotional meaning? Charlie McCoy’s bass playing. Outside of Keith Richards’s on “Sympathy for the Devil,” the best ever.

Hi Greil: I’m glad to see you’re doing well.

I agree with you that the Dylan 1974 box is a Sisyphean listening endeavor. But I found it enjoyable. And as one who has heard 27 different live versions of “Whipping Post,” “Jack Straw,” and “In A Silent Way,” I don’t mind the repetition if the band is good, and The Band was very good on that 1974 tour—especially Levon Helm.

Anyway what most struck me—and made me wonder what you thought—were the versions of “Nobody ‘Cept You” (especially the Seattle version). I feel like Dylan could have introduced it by saying, “Here’s a new song that will be an outtake from an album I haven’t recorded yet.” It sounds to me like it could fit right onto Blood on the Tracks. It’s like in the midst of a tour in which he is running roughshod over 10,000 people nightly with his older songs—as if to say, “Remember me? Now try and forget about me again”—he’s already planning his next move, going from electric back to folk in a way that will be another Dylan game-changer.

That’s how I hear “Nobody ‘Cept You.” And maybe why he only played it four times. Having figured out what he wants to do after the tour, he can’t wait to get the tour finished by just playing the hits.

Thoughts? Cheers to you. —JEFF

You're right. The song is a gem in these shows. It stands out. It's different. It's unheard. You aren't sure what you heard. By its words it’s an obvious song. As a sentiment, a gesture, an embrace, a wave goodbye, it gives the lie to a lot of what is being played around it.

I like your idea for introducing the song—what he should have said. Riddles inside riddles.

Hi Greil!

I was a former student of yours at the New School (the Old Weird America seminar in spring 2013), and I wanted to ask if you had any thoughts about labels suing the Internet Archive for $621,300,000 over their Great 78 Project, which digitized thousands of old 78 records to create a free online library of specific recordings with all the crackles and quirks of their physical containers. I know you believe in the preservation of old music and I think that having the archive of what specific records is useful because it gives us not just a sense of the song, but the sense of the song as people actually have listened to it over the years. Do you think the lawsuit has any merit and these sorts of sites shouldn't just be free to the public, even if the streams labels claim to be losing are only worth less than a penny each if streamed on Spotify? Curious what your thoughts are, since I feel like you have a good perspective on the preservation of old music to share.

Thanks —AUDREY ZEE WHITESIDES

Dear Audrey—Good to hear from you again. I'm not a lawyer, but I do know something about the doctrine of Fair Use and its recent alterations. If the material in question has been licensed to Spotify or some similar platforms, then the proprietors of the music rights in question are protecting their copyrights, and unless Internet Archive can prevail in a claim that they are functioning as a public library, they would presumably have to secure licenses and/or pay fees. Copyrights have to be protected, which means not only that rights have to be properly registered, and renewed, but that they must be exercised. If, for example, as happened throughout the 1950s and 1960s, when reissues of commercially released old folk music, country, and blues recordings were common, the people reissuing the music did not obtain permission from the original labels to do so—the most famous example being the Harry Smith’s 1952 American Folk Music compilations on Folkways. But this music was not otherwise available. The labels that owned the recordings had typically made no attempt to exploit, which is to say protect, their copyrights, by reissuing or making other use of the material, since its original issue, and in many cases did not even know that they possessed or owned the material.

So if the material Internet Archive has collected is not commercially available, they have a claim that the work they are using is unprotected, and the copyrights are inactive. Otherwise they would have to claim that they are a non-profit providing educational services not available in any other form.

I don't put any stock in making available material with pops and sticks and scratches, so that people can experience what it was like to hear recordings in their original or authentic form. Except in the case of labels like Paramount of Grafton, WI—whose 78s sounded so bad collectors joked that they sounded as if they had been made out of dirt, until it was discovered that the records were made partly of clay from the banks of the Milwaukee River that ran through town—and even in some cases from Paramount, 78s often had a pristine, deep, complex, and warm full sound. There are certain Son House recordings of which only single, damaged copies have survived, and their reissue on labels like Document are unhearable. That's not what the people who bought them heard. The late Ed Ward once wrote a wonderful short story about white record collectors in the 1960s encountering an old woman in the south who, they were able to determine through practiced questioning, had a vast collection of Delta blues 78s. They almost had heart attacks salivating over the find they were about to get their hands on. The woman, who explained that she no longer listened to sinful blues records since accepting Jesus, led them to her backyard garden, where all of her 1920s and '30s 78s were being used as planters for her vegetables, and were thus irredeemably warped by the sun and ruined by moisture in the soil.

All that said, if labels are truly suing for more than half a billion dollars in damages—i.e., money they would be claiming they have lost because of copyright infringement—they're insane. Unless they find the right Trump-appointed judge taking a kickback.

Decades ago, you didn’t appear to share many people’s views of George V. Higgins’s crime novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle. You described his writing as literarily pretentious. I could see your point about his succeeding novels like Cogan’s Trade, but if you still feel this way about TFOEC what makes it seem pretentious to you? —BEN MERLISS

It seemed he wanted to make it clear he wasn’t just another run of the mill crime writer, and he succeeded in that. But for me the book was cold.

One thing I love about Mystery Train is your ability to place rock and roll artists in earlier traditions, to find commonalities with "ancestors" (between Melville and Robert Johnson, Sly Stone and Staggo-lee, Elvis and... everyone?). An American artist I've spent a lot of time listening to in the last few years is Captain Beefheart, but as someone not raised in the US (I'm in Alberta) and not well steeped in its myths and histories (not to mention that I only first heard Trout Mask Replica about five years ago) I'm wondering if you can place him in any specific tradition or archetype. Let's say you were paid a million dollars to write a sequel to Mystery Train on the condition that you covered the Captain. Can you fantasize about where you might go? —TERRY

Given the territory the book was trying to map, Captain Beefheart was a natural, even, looking back from now, after 1975, when the book was published, so much remained to surface or be made, from his mind boggling Robert Johnson remake/remodel of “Terraplane Blues” into “Tarotplane,” the similarly revolutionized “You’re Gonna Need Somebody on Yer Bond,” the albums Ice Cream for Crow and Doc at the Radar Station. As I lined out in an obituary in Artforum, I could have tried to make a chapter out of nothing more than the distance between his 1965 Bo Diddley cover “Diddy Wah Diddy” and “Orange Claw Hammer” from Trout Mask Replica four years later—or the absence of distance. But the criterion for who might belong in the book was someone or something that hadn’t been written about extensively or well—and Langdon Winner, in Rolling Stone, had already covered both bases with Captain Beefheart. It was his subject, his territory, and I’d have been poaching, or trespassing.

Stumbled across this recently. My normal reaction to such absolutes: Whirlwind apoplexy. I've been passing this around, though, to folks more learned, more seasoned—and less prone to apoplexy—to see whether anything more nuanced might be gleaned.

Longtime [Blind Boys] leader Clarence Fountain, who died in 2018, once said that Lou Reed could not sing his way out of a paper bag. Clarence meant no harm. Lou and the Blind Boys collaborated on a number of projects over the year. Clarence personally liked Lou and complemented Lou's guitar playing. Lou Reed sang with style. His fans are not wrong to admire him. When you appreciate where Clarence came from, however, his paper bag statement seems fair.

Clarence had shared the bill with Mahalia Jackson when Lou was in kindergarten. He'd toured with Sam Cooke while Lou was sneaking his first smoke. The average big gospel quartet program during the genre's heyday featured maybe forty vocalists more gifted than Reed. A half dozen of Fountain's co-leads in the Blind Boys—men unknown to history—sang with more spiritual ferocity, more sublime talent, greater technique, and greater emotional subtlety than any member of the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of fame or the Current Top 40...

--Preston Lauterbach, from his introduction to Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story, written with the Blind Boys of Alabama. —ANDREW HAMLIN

Lou Reed couldn’t sing his way out of Clarence Fountain’s paper bag. But maybe Robert Plant could have, by blowing it up. I don’t doubt that there have been countless singers to pass through the black church who, to put Preston Lauterbach’s integers of value into different words, could sing as if they were closer to God than Van Morrison. Or Otis Redding. Or Aretha Franklin. Or Sam Cooke. (Wait—they are in the Rock Hall.) Or Mahalia Jackson. (Hold on—she is too!)

Rock ‘n’ roll singing is is not about how close you can get to God. It’s about getting that sound you hear in your head into the world. Lou Reed wanted to sing like Nolan Strong. He wanted to join the Chantels (once, he got to perform with them). He wanted to sound like Dion. But he couldn’t. So he had to find his own voice. That is rock ‘n’ roll: land of a thousand paper bags.

Hi Greil - Hope this finds you well. I'm wondering if you've had the time or inclination to investigate the steady stream of unearthed archival recordings by the late Arthur Russell. He's been elevated to cult figure status over the last twenty years or so. As someone who followed the New York scene fairly closely during the Eighties, I was only dimly aware of him. I treasured the Loose Joints single "Is It All Over My Face" and knew that a guy named Arthur Russell was its mastermind. A few years later I heard he was involved with the short-lived but vital rap label Sleeping Bag Records. And that's about it. Today I much prefer his jazzy dance tracks to his ethereal (not to say wispy) singer/songwriter material. "Tiger Stripes" by Felix is a good one. And the 2004 CD collection The World of Arthur Russell is the best place to start, and possibly end, with him.

If I had to hazard a guess, I'd imagine none of this is up your alley but I wouldn't have suspected you'd be so into, and insightful about, Lana Del Rey. So it seems worth asking. Thanks and take care —MARK COLEMAN

This is unknown territory for me.

Hi Greil. First thank you for your work. I have followed your writing since the ‘70s and have always found it inspiring. I find the elegance and conciseness of your style in the Gatsby Book breathtaking.

I have for many years been searching for a piece I read in a collection of essays. I think it must have been an early piece describing rock ‘n’ roll as a form—a ‘what is it’ article. I think it might be in Rock and Roll Will Stand or a later edition of that but I’ve had no luck. It might have even been called “Rock ‘n’ Roll.” It has stayed with me all these years but I would love to read it again. —JOHN GIBSON

Dear John,

Thank you for your kind words about my work.

The piece you're thinking about might be "Who Put the Bomp," which was in Rock & Roll Will Stand, my first book—I edited it—from 1969, from Beacon Press; there was no later edition. Or you might be looking for "Rock-a-Hula, Clarified," a long investigation/manifesto about what rock 'n' roll was in 1971, in a first piece for Creem, when I'd submitted written work for a Ph.D. oral exam and had to wait a month while the committee members read it so I wrote that to fill the time (I essentially failed the orals, but was passed, with a host of conditions, because two of the three people judging knew I was better than I'd done; in any case I never pursued the degree any further). That's never been included in a book. I'm not sure why. I stand by every word of it.

There are links below. Please write back and let me/us know if this is what you were looking for and if so what you think.

“Rock-a-Hula Clarified”: Part one, two, three.

Hi Greil. In November of 2022, just coming off having seen Tropical Fuck Storm play in Brooklyn on their last US tour, I asked you the somewhat ridiculous question of whether I was on defensible ground claiming they were the greatest working rock & roll band (this with me having seen probably 0.00001 of the currently working bands in the world). You answered graciously, but also said you hadn’t “been lucky enough” to see TFS. I just came from seeing them in Brooklyn again. I am rocked. They play San Francisco on October 10, and I hope you will be lucky enough to see them then.

Incidentally, since you were the one who alerted me to TFS via The Drones, you might be interested, if you weren’t aware, that on their Bandcamp page there are five albums’ worth of live Drones recordings. I have all of their studio albums and so will have to pick through these to find out what’s redundant and what’s not. I have determined, though, that the “Jezebel” from Sweden on Volume 4 is a massacre, in the very best sense. —EDWARD HUTCHINSON

Thanks for the Swedish “Jezebel” which I will look for. I’ve been snakebit about seeing them. I’m always somewhere else. As with this time, as I won’t be in town for that night. More on what you saw and heard?

Hi Greil, a quick note to say thank you for mentioning the Punk and the Pit documentary. YouTube comes through again, and tho the uploader apologized for some audio drop-outs, I heard none during my quick scroll-through. What a brilliant idea and thanks again for the discovery. Here's the YouTube link. —CHARLIE LARGENT

Thanks for this. I’d been thinking about transferring my old VHS copy to DVD and this makes that happily redundant. I’m so glad it’s out there.

I remember watching The Creeping Unknown, the first film in the series—like Quatermass and the Pit aka Five Million Years to Earth based on the earlier BBC tv series—on late night tv when I was about 12 and being scared like I’d never been before. The whole project is one of the great dramatizations of postwar dislocation and uncertainty. Everything is there: the Rosenberg case, McCarthyism, the UK Soviet spy ring, the certainty of nuclear war. And so much more.

Reading the terrific Creem article about Dylan and The Band's 1974 tour, what strikes me most is the part right at the end in which, for all intents and purposes, you foresee Blood on the Tracks: "...it is impossible to believe that the vitality he must have received from the audience will not find its way into new songs as strong as those he shot off the stage. ... This time, Dylan went to us, and it should make a difference." It most certainly did, and I'm wondering whether, when you first heard that next album, you remembered what you'd written and were proud that you were right. —HAROLD WEXLER

I’m glad you like the piece. But the connection you’re suggesting never occurred to me. I wasn’t predicting anything that came to pass. What was striking then and what’s striking now is how different “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Idiot Wind” and “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” were, in every way, structure, rhyme scheme, the ebullience and sense of discovery in the music—and how, now (and thank the gods for the Minnesota recordings, none of this applies to the dull and tired New York originals of those songs), you can hear each carrying and driven by a reach as great as that brought to “Like a Rolling Stone” years before, and the grasp too. That last affirming three-part count at the end of “Tangled” still gets me every time.

Really, the first thing that struck me about that album were the terrible Pete Hamill liner notes. Somebody made a mistake; they were gone before you could turn around.

Greil - so great to read your experience with the Dylan/Band concerts—wish I hadn't just been a child at the time with no awareness of Dylan yet. (My first contemporaneous Dylan LP purchase was Desire.) Anyway... please define the phrase "store porching" which you used in this essay. Google comes up utterly blank! —MARK DROP

The term comes from musicians in a small town setting up on the porch of the local general store and playing to attract customers or for tips, but it also carries the connotation of making a raucous noise and coming on strong.

Dear Greil,

Sometime ago a huge Del Shannon box was released that you said you had to have. Did you obtain it and what’s the verdict?

This was prompted by my playing Del’s Live In England the other day. The version of “Runaway” at the end is tremendous. —CRAIG ZELLER

It’s Stranger in Town, 12 CDs. But for me the 1973 Live in ‘England disc is ruined by the hamfisted drumming that’s right up front on every song. Del is right on top of it, but for me the one time he took the song to new worlds was elsewhere, redoing it for Crime Story in 1986. The same disc also collects singles from 1972 to 75, with the first a cover of Timi Yuro’s “What’s a Matter Baby.” Hers revels in vengence, his is forgiving, but it’s so right—it could have been written for him.

Dear Greil,

Have musical differences ever gotten in the way of a friendship with a fellow critic? —CRAIG ZELLER

I can only think of two instances, one serious, that led to a distinct lack of communication over time, that was never really hashed out or resolved, just allowed to go away, over Public Enemy’s toleration for if not somewhat occluded endorsement of antisemitism, and the other kind of stupid, on both sides, that led to a “we just can’t talk about this,” as in never mention the subject except in print, having to do with the wondrousness or irredeemable shtick of Lucinda Williams, who, as long as there are tribute albums or concerts to partake of, will never stop inflicting herself on those too dead to defend themselves.

Your excitement about the new Dylan/Band live recordings would be infectious if I wasn't already champing at the bit to hear them. Your latest newsletter, with the 1974 Creem article describing your reaction to a bootleg that confirmed (and perhaps enhanced) your reaction to the live performance, somewhat mirrored my own experience: I was at the opening night of the tour in Chicago on January 3rd of '74, and saw them again precisely a month later in Bloomington, IN. The live performances were cataclysmic but the double vinyl release was explosive in a different way... heresy, I know, but I'd never warmed to “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I'll Go Mine)” till I heard the the live performance on record. It's now in my top ten Dylan recordings, live or otherwise. It felt like I carried that album with me wherever I went, even paying the price for leaving it in a VW bus (what else) on a hot summer's day (it survived the experience, and then some.) I hope we'll hear more from you about the set after you've lived with it for a while. —CHARLIE LARGENT

I’ll be replaying certainly shows. One big regret: they—or Dylan himself—only played “As I Went Out One Morning” once, at the Toronto show not included in the box set. You can find it, but it should be part of the record, in both senses of the word.

"Rock-a-Hula Clarified" was in the first issue of Creem I ever saw, on a newsstand in Boulder. It starts with a variation on the classic joke: John Simon, Erich Segal, and Little Richard walk into a bar...or the Dick Cavett Show. It changed everything for me. Thanks for that, Greil.

Even Greil cops to the double-standard on Harris v. Trump, i.e., while Trump can go out and behave and say things that would get any other public person, let alone politician, drummed out of the public sphere, Harris has to be perfect for whatever reason. I mean, the choice is between a rational, intelligent, capable, experienced public servant and a goddamn lunatic and people want to nit-pick on a question she may have answered less than perfectly. Sheesh!

Re: Bob Dylan introducing his songs onstage, maybe he did that in Greenwich Village days or god help us, on the '78 Vegas Tour, but he certainly was not going to be telling an audience about a particular song, i.e., where it came from, what it means, hey buy my new album, it's great! in 1974 or since. He is not that kind of person or performer.

Glad the Del Shannon box set came up as I was the guy who brought it to Greil's attention almost two years ago when it was released. No, I haven't gotten it yet, but I've come to realize that Del was a pretty good songwriter, although he never eclipsed Runaway. But he knew the craft pretty well, although largely a hack of sorts, like most or all writers. His 1967 LP The Further Adventures of Charles Westover (his real name) is great and I think the fact that it failed commercially at the time, sort of killed his spirit and he became resigned to Dick Clark oldies tours until Tom Petty re-discovered him and tried to help him later. Did his suicide come about because of a bad reaction to Prozac? Was he disappointed by not being asked to replace Roy Orbison in the Traveling Wilburys as rumored? I don't know, but here was a guy out of nowhere who made a name for himself as a good rock 'n roll artist, however unlikely that was for a homely looking guy from Michigan and left behind songs and a style which were pretty unique in their own right. As one of his early LPs read: Hats Off To Del!