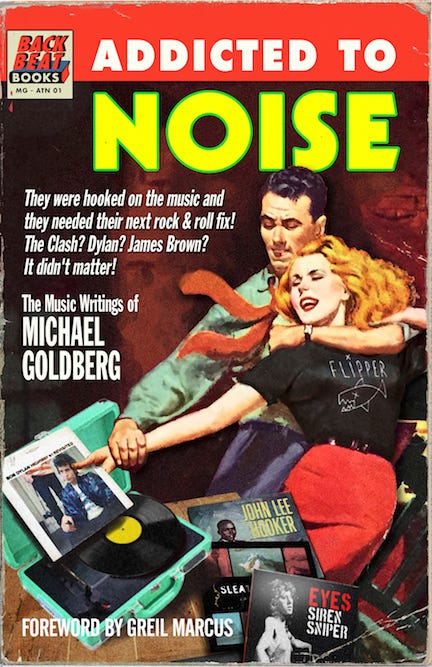

Foreword to Michael Goldberg's Addicted to Noise

I took notice when I first read Michael Goldberg in the San Francisco Chronicle. He appeared to be a stringer, a byline appearing occasionally and unpredictably, and then more often, then something to look forward to. It was the late seventies or early eighties. It wasn't that he was covering bands and records others weren't. He brought certain values to his work that were unmistakable and seemingly contradictory.

These were empathy and ambition. This was someone who clearly meant to get his name out there, to make you pay attention, to make you do what I was doing—looking for his name. He was careful with his facts—Goldberg is, I think, a reporter before he's anything else. There was a sense of hurry in his writing—you could get the idea he wrote a lot more than was getting into print. But there was no narcissism in that ambition, no preening, no persona, none of the Wouldn't-You-Like-to-Buy-Me-a-Drink smirk of the likes of Jeff Goldblum's rock critic in the 1977 Between the Lines, which was the likes of all too many real-life music writers then, before, and after.

It was clear that this was someone who was interested in what others had to say. Who came first, the listener or the writer? Maybe the writer, because that got him in the door, but after that, he wasn't like the other people the people he was talking to had talked to before. That evidence was there from the first and it's never lessened. In these pages, that might be Brian Wilson or Flipper, Gil Scott-Heron or Van Morrison, Rick James or the Minutemen. Right off, whether these are profiles, interviews, or, as you'll find here, raw Q&As more formal pieces were drawn from, you are hearing questions other people don't ask, an honest curiosity that has nothing to do with a catchy headline or even a pull quote. You can feel the atmosphere: someone has walked into a room with a pencil in his hand—as the words go in perhaps the first song about a music critic, not counting Chuck Berry's aside about the writers at the rhythm reviews—and suddenly people are relaxed. They get the feeling that this person is not Janet Malcolm's reporter: the person no one able to conquer his or her own vanity should ever trust. He isn't after your secrets. He doesn't want to ruin your career to make his. He doesn't care what you think you need to hide. He actually is interested in why and how you make your music and what you think of it. So people open up, very quickly, and, very quickly, as a reader, you're not reading something you've read before.

For me, this stands out most dramatically, in ways that aren't dramatic at all, in the work here on Sleater-Kinney and Robbie Robertson. You can feel inner lights go on: whether eager, as Janet Weiss, Corin Tucker, and Carrie Brownstein are, or ruminative, digging down, as Robertson is, you feel that Goldberg's uncostumed directness ("What do you think gave you, particularly early on, the confidence to believe in yourselves? Where'd it come from?"), which is also an invitation to depth, produces responses that are unfiltered, unguarded, unprotected. You can feel that the people in Goldberg's pages never talked to anyone the way they're talking to him before—not close friends, who wouldn't ask big-deal questions, not other writers, who wouldn't know to.

Questions of success, of career, of what's next, of the-new-album, are a different language here, if they're here at all. "I think that's really crucial that just as soon as I started playing music when I was 18, there were all these people that completely encouraged me and wanted to put out a record even though I had played four shows," Tucker says. "And they were doing that for all these other people in the community too. You were part of something that was encouraging this underground, that you wouldn't have to rehearse for two years before you cut your first LP." In these pages, against that, Robertson speaking in 1987 on why, 11 years before, he, in Goldberg's words, "shut down The Band and walked away," leap out, he and Tucker talking about the same thing from different poles of gravity: "I just had nothing left to say. I would look around, and I would see all these other people who had nothing to say either, but they insisted on making records and I thought, ‘I don't want to do that.’ I felt like I'd made a hundred records." He talks about why he doesn't want to talk about Richard Manuel of The Band, who had killed himself the year before: "I can't tell other people's stories. It's not right."

The pain of loss in what both people are saying is undeniable, but there's no self-pity, no begging for alms, which is to say admiration: Look what I survived! The absence of cliché, on the part of the interviewer but more so on the part of the person being interviewed, is even more striking—and you can reach the conclusion that Tucker, Robertson, and so many others here don't speak in clichés because they've heard that Goldberg doesn't, and, responding to his empathy, reply in a way that communicates the emotional fact that they want to speak on the same level, as if the usual suspects from any musician-interview aren't good enough for him, and by extension his readers, and by extension your fans, and by extension yourself.

All through these pages, you can hear the people Michael Goldberg is talking to and talking about reach the same conclusion. I can trust this guy, they say. What the hell.

—Oakland, California, Dec. 2018