1. Till, directed by Chinonye Chukwu (Universal). The picture opens in a car on the streets of Chicago in 1955. Danielle Deadwyler as 33-year-old Mamie Till and Jayln Hall as 14-year-old Emmett Till, who’s about to leave for Mississippi to visit family, his first time traveling by himself, are happily singing along to the Moonglows’ croony doo-wop hit “Sincerely” from the year before. Then a shadow of distraction passes over Deadwyler’s face, and as the music fades just slightly on the soundtrack she loses the thread of the song. It’s a scene of pure foreshadowing: the whole movie to come is present in this moment

The film builds towards Mamie Till’s insistence that Till’s body be shown at his funeral in an open casket, so the whole world can see the ruin his killers in Money, Mississippi, made of her son’s face, which is no longer a face, which no more resembles a human head than it does a stomped and filthy soccer ball. The image, on the cover of Jet magazine, has in all the years that followed never really been unseen. But what is it about the story that has kept it alive—more than alive, but repeatedly present—for 67 years? If he had lived, Emmett Till would be 81, and likely forgotten. His accuser, Carolyn Bryant Donham, is now 88—except in Percival Everett’s 2021 slapstick detective story, The Trees, where Granny Carolyn dies of a heart attack in 2018 in Money, with, in chair facing her bed, a corpse that except for the suit it’s wearing looks exactly like Emmett Till as his body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River—is not forgotten. On December 3, outside Bryant Donham’s apartment in Bowling Green, Kentucky, protestors gathered to demand her punishment for her false testimony at the trial of her husband and brother-in-law for Till’s murder. “As thou has done,” said Dr. E. Faye Williams of the Dick Gregory Society at the gathering, quoting Obadiah 1.15, “so shall it be done to you.”

2. Taylor Swift, Midnights (Republic). Last month there was some controversy over Bob Dylan selling $600 inscribed copies of his The Philosophy of Modern Song that turned out to have been signed by Autopen. With ten of its 12 tracks taking the top ten spots in the Billboard Top Ten in the last week of October—it would have been the even dozen if they could have figured out the math—this is the musical equivalent.

3. “Tom Petty Estate Issues Cease and Desist Order to Kari Lake Over ‘I Won’t Back Down’” (news item, November 22.) For the record: After losing the Arizona governor’s race to Democrat Katie Hobbs, the Republican Kari Lake posted a video scored to the 1989 Tom Petty song—which had been used in the past by, among countless others, Dr. David Gunn, who performed abortions in Florida, as, before he was murdered in 1993, he faced a crowd of anti-abortion protestors, playing the song on a boombox, and by the Klansman David Duke, after he came within two points of winning the governor’s race in Louisiana in 1991, as the theme music to his radio show. “Tom Petty was enraged by any sort of injustice,” his publisher Wixen Music wrote to Lake. “Without question he would have been outraged by your failed campaign for Governor, which was filled with distortions, lies, smears, promoting hate, and attempting to undermine our democracy. Using his music to promote yourself and your despicable cause is revolting and antithetical to everything that Tom and his music stand for and mean to millions of people.

“Tom sang ‘I Won’t Back Down’ at America: A Tribute to Heroes benefit concert for victims of the 9/11 attack. Not backing down to hatred, violence, and an attack on our democracy. The opposite of what you stand for. Using this song to promote your warped values is not only illegal as outlined above but an insult to Tom’s memory, his lyrics and music, and the tens of millions of fans who cherish his legacy.”

4. Pistol, created by Craig Pierce, directed by Danny Boyle (Hulu). A six-part series taking off from guitarist Steve Jones’s good 2017 book, Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol (“Pandora’s box was open for fucking business,” he says of the group’s first show), but taking off into another world—the world of the unrepeatable artistic event as opposed to the repetitions of ordinary life—when Anson Boon’s Johnny Rotten roams the stage as if it’s a cage and opens his eyes as if they’re gates to the underworld. I saw Johnny Rotten on stage, and he was frightening, but Boon is terrifying: more focused, more clear, more convincing that he doesn’t care what comes of his performance as long as something does. It’s a transportation, made by an actor, singing out of his own throat, on a TV screen, that fully captures what Green Gartside of Scritti Politti says of seeing the Sex Pistols in Leeds in 1976. “That night was a kind of call that had to be answered,” he says in Gavin Butt’s recent and horribly titled No Machos or Pop Stars: When the Leeds Art Experiment Went Punk (Duke): “a decision had to be made about an absolute transformation in what was possible, in what one should do, and what one could do, and what one ought to do. Right there and then. I know it sounds completely mad, but that’s what I came away thinking and feeling.”

Completely mad: you see it happening. When the Sex Pistols play a prison, a mental hospital, and as Boon delves deeper into himself, or some spectral self, a demon that will last only as long as you can stand to watch, it’s utterly believable when someone in the audience, which doesn’t look or feel like an audience, which seems like some random assemblage of passersby, stands up and begins to move as the person on stage is doing, as if he or she has no idea where this self came from but isn’t going to let it let them loose. It’s a double dance of self-affirmation: if this person up there can say who he is without being afraid of the noise in his own face or his own words, who says I can’t?

5. Gang of 4 at the Independent (San Francisco, March 21). The band formed in Leeds in 1976—guitarist Andy Gill and singer Jon King were at the same show that left Green Gartside so shaken—and put out their first record (a 45 of “Damaged Goods,” “Armalite Rifle,” and “(Love Like) Anthrax”) in 1978. This night they were King, who was 66; original drummer and one-song-singer (“It’s Her Factory”) Hugo Burnham, five days short of 66; Sara Lee (“Somewhere between me and Jon,” Burnham guessed), who replaced original bassist Dave Allen in 1981 and glowed with happiness to be back, going up to her mic to sing backup as if she was always there; and David Pajo, 53, standing in for Gill, who died in 2020. The band, as different from everyone else who turned up when the first wave of punk hit the beach and pulled back as any could be, left a legacy of unsolvable music that people have been exploring ever since. “The No Alcohol and Narcissism Tour!” Burnham announced; the small club was full, and eager to find out what the band had to say and how they were going to say it.

There was nothing recycled or even necessarily familiar in the cut-up, purposely uncompleted music of the songs themselves, all of them over 40 years—I was going to say old, but that doesn’t fit: I’ll say since they were first heard. Pajo, in a suit that seemed to fade into a stocky body and a thick head of hair, made his own presence as he spoke or sang the comparatively slight Gill’s lines in “Damaged Goods” or the back-against-the-wall redundancy saga “Paralyzed.” The most extreme bets of Modernist painting remain fresh, new, unlikely: Mondrian’s lines and colors, Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pollock’s Alchemy. In the same way, the discontinuous, squared-edge figures in Gill’s guitar theory and practice—and was theory before it was practice—in Pajo’s hands still feel surprising, a different language, as fierce an argument against traditional guitar music as anyone other than maybe Link Wray has ever understood it. And he, like King, dancing across the stage as if looking for markers that never appear, is playing a role. As the set moved through the most complex and furious songs, the band’s dramas of false consciousness in which the subject apprehends the slavery of their conditioning and in a panic has to decide whether to resist or embrace it, as in “At Home He’s a Tourist,” “We Live as We Dream, Alone,” “I Found that Essence Rare,” an inflamed “Damaged Goods” as a close—you might realize that as songs these pieces are more like plays, with multiple parts, stage directions, positioning, the musicians pushing their characters as much as any line of rhythm. The night air felt sharper leaving than it did going in.

6. Dark, Dark Hours on General Electric Theater with Your Host Ronald Reagan (CBS, December 12, 1954). Ah, the wonders of YouTube. Here’s James Dean, a year before he changed the world in Rebel Without a Cause, playing a hipster already older than his Jim Stark would be, and yet, in the slipknot of cultural time, acting out that movie in advance. Here he’s Bud, a cool-cat thief dragging his pal Peewee to Dr. Ronald Reagan’s house to get a bullet pulled out from a robbery gone bad. Reagan puts the U in upstanding; he wouldn’t think of turning a wounded man from his door. Peewee is bleeding to death: he needs bop, Bud commands weirdly. Then it isn’t weird: Bud grabs a radio, finds a station, and the music is fast enough to make you believe the comatose Peewee is singing I don’t NEED no doctor! in his dying brain. It’s a scramble: seeing the bursting heart of the 1950s holding a gun to the face of the cold, cold heart of the 1980s scrambles time even more.

Something in Reagan’s steely demeanor says he knows who’s going to live and who’s going to die, and not just in this half-hour plot. But who has really outlived who? Who still looks like a future that hasn’t come to pass?

7. Scott Ostler “World Cup taken to the cleaners in Qatar’s epic feat of sportswashing,” San Francisco Chronicle (November 8). On the Qatar World Cup: “Almost all the country’s construction, the stadiums and hotels, is the work of foreign laborers. Many of the laborers have faced brutal and sometimes-deadly working conditions, squalid living quarters, and low and sometimes-unpaid wages. Why don’t they just leave? Because they are not allowed to do so. Many had their passports confiscated as a condition of being allowed to work in Qatar. They can check out any time they want, but they can never leave.”

8. Jann S. Wenner, Like a Rolling Stone: A Memoir (Little, Brown). “I had no time to be a dutiful son, being so full of myself and the important things I was doing, the important people I was meeting, and the important drugs I was taking.”

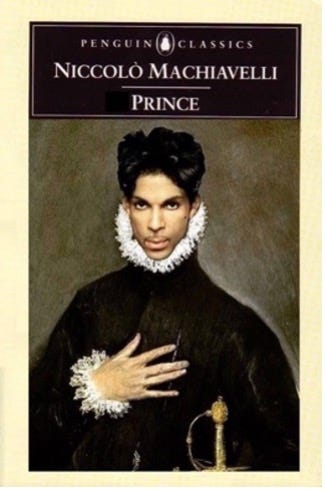

9/10. Hilton Als, My Pinup—A Paean to Prince (New Directions) and Nick Hornby, Dickens and Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius (Riverhead). “This book is about work,” Hornby says on the last of his 156 pages of text. As a working author himself for 30 years, with novels and books of criticism and memoir and screenplays and television series, Hornby is in awe of the production of Dickens (1812-70, first book 1837) and Prince (1958-2016, first album 1978)—despite fights over money, rights, ownership, marriages, love affairs, all but shocked by the staggering, who-could-possibly-keep-up-with pace of the novels, speaking tours, albums, bands, performances, letters, archives assayed in their almost identically foreshortened lives. In his characteristic way, Hornby puts the reader at ease, invites the reader into his thoughts, musings, and passions, never pressing, but always full of wonder, so that soon you are thinking with him, and as Hornby speaks of his subjects, and also himself, and also anyone with artistic aspirations of their own, everything is interesting: “One might at this point ask the question, of both Prince and Dickens, ‘Why not just be happy? Things are going great. You’re world famous. There’s plenty of money. There will be more. Chill.’ They were both complicated people, and therefore though one can provide some simple answers to the question, maybe the root cause is buried deep in their childhoods. Here is one of the simple answers: artists have a freelance mentality. There is always a fear of failure, a sense that next book or record will not only fail, but somehow render all the others unreadable or unlistenable. Tastes change. People have their moment in the sun and then the sun moves on to somebody else. Our careers seem built on nothing—words, ideas, sand—and we can all too easily imagine the plummet back down to earth in a way that doesn’t seem possible if you’re a lawyer, or if you have a skill you know people are going to need tomorrow, next year, the rest of your working life, like plumbing or dentistry.”

Als’s book is 39 pages of text, but so intense that when you come to the end—with a graceful elegiac paragraph (“As she lay dying, her white skin took on a number of shades or different colors, as if she had absorbed those aspects of Prince’s race or my race that belonged to her beloved’s race too”)—you feel like you have been on a long voyage and not sure you’re home yet. This is a love letter—the epigraph from Prince is “If I was your girlfriend”—to Prince, but not only to Prince: to another man in Als’s life, to other pinups he will never meet, as he did meet Prince, in encounters so wispy, so like shaking Prince’s tiny hand, that they seem like daydreams. There are strange moments that sing with sudden insight. If the suits of Prince’s bodyguards remind Als of “the neat haberdashery worn by the late Elijah Muhammad Nation of Islam sentries in the 1960s,” Prince “was a different kind of messianic presence: ecclesiastical-minded, to be sure, but still a perfect candidate to be left behind should the Rapture come”—I’ve been puzzling that out for days. But this sense of suspension is the key to the swaying power of Als’s gaze as he looks at Prince, at any moment in either man’s career: the book is set loose from ordinary time by the unacknowledgement that Prince is dead. “Prince’s best songs . . . have always been,” Als says; “what Prince has rewritten in his thirty-five year career,” Als says. His “hometown of Minneapolis, where he lived until recently,” Als says, as if Prince is now living somewhere else—not heaven or hell, but Nashville or Palm Springs. That last paragraph about someone else’s death blows back on the book, from its first page and on from there.

Thanks to Andrew Hamlin and Steve Perry.

Love Hornsby's "...if you're a lawyer or if you have a skill...."

Love Hornsby's "...if you're a lawyer or if you have a skill...."