The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Emmett Miller

September 2001

With a title as evocative as Where Dead Voices Gather, all Nick Tosches has to do is bring it to life. He does this in his new book about Emmett Miller (Little, Brown and Company), one of the last of the blackface minstrels, a mysterious, marginal figure who has obsessed Tosches for three decades.

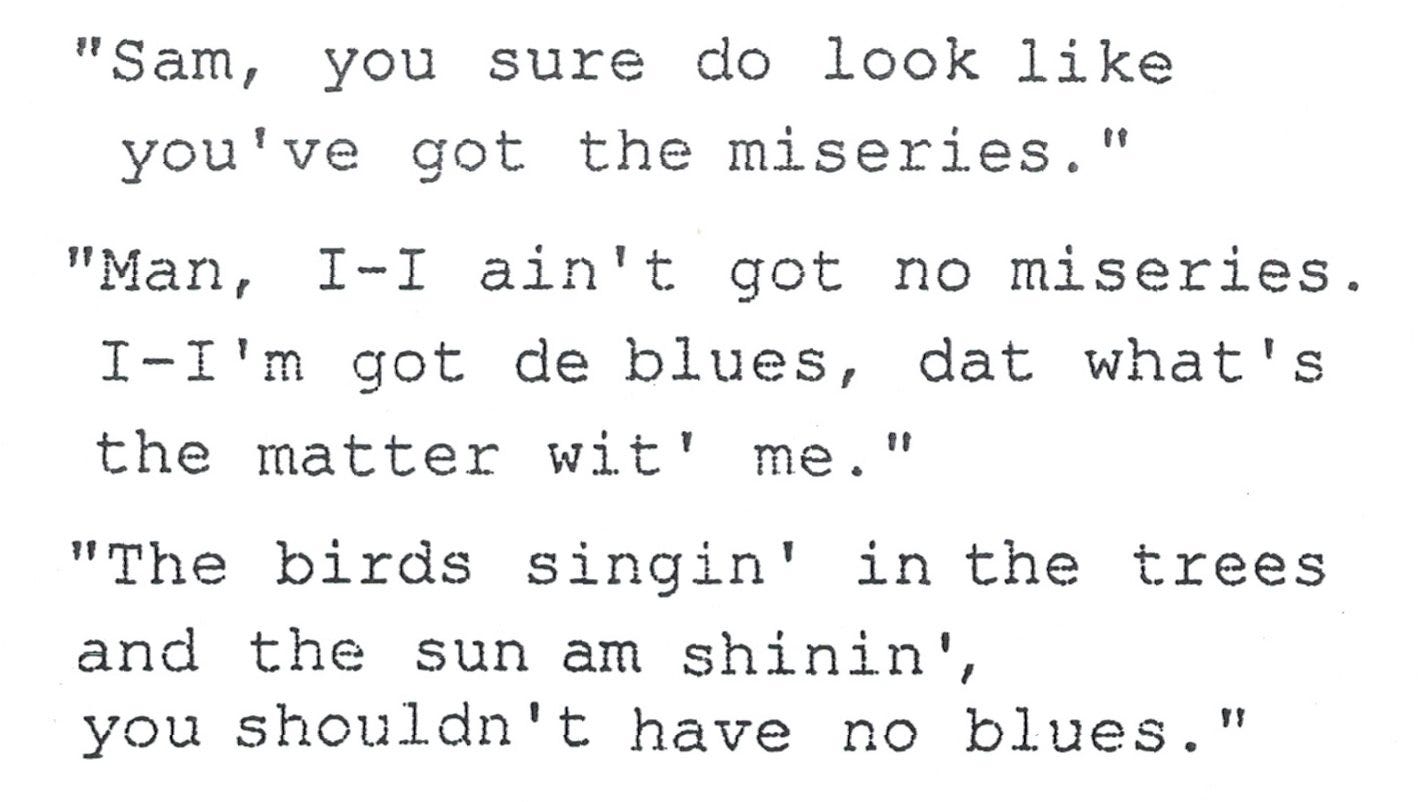

Hank Williams must have learned his signature "Lovesick Blues" from Miller's 1925 recording; Miller's contemporary, Jimmie Rodgers, commonly known as the Blue Yodeler, the Father of Country Music, almost surely must have heard precursor Miller's strange yodel, his "trick" or "clarinet voice," his "break-voice falsetto bleat," as Tosches names it. Soon you can begin to see Miller everywhere, in Amos 'n' Andy routines, in Abbott and Costello's "Who's on First?"—a white-faced version of a blackface version of the traditional African-American insult game, the dozens. You hear Miller in the brags and taunts of gangsta rap, where the artists do not even know that the negritude they purvey is a matter of "'blacks imitating whites who were imitating blacks who were imitating whites.’"

A big so what? here is a perfectly legitimate response. Who cares about Emmett Miller, born in Macon, Georgia, in 1900, died there in 1962, a man who once had a career, made records and was soon forgotten? Why read page after page on 1920s minstrel show tours of the South lovingly, even numbingly, reconstructed from reviews from the likes of the Asheville Times, which in 1927 named Al G. Field's Minstrels, with which Miller was then starring, an institution that "filled a place in the average American's credo similar to that held by the Democratic party, castor oil and the Methodist church"? Why even listen to the corny and weird 1996 Sony release The Minstrel Man From Georgia, which today is the only way you can hear Emmett Miller?

The answer is, you don't have to do any of that to be sucked in by the vortex of historical indeterminism, cultural uncertainty, racial instability and the plain magic of a writer's quest that is Where Dead Voices Gather. But that vortex is not found in Tosches' summation of Miller's appeal, fine as that summation is, as it takes off from Miller's 1924 "The Pickaninny's Paradise." That number, Tosches says, "tugs at the heartstrings; but the paradise itself of which he sings seems in the end not far from Nightmare Alley, and his singing as much a tug on the sleeve as on those strings.

"That phrase: trick voice. Let it fall from the light into the darkness and it, too, becomes sinister. The barker, after hours, confiding to the geek: 'Guy here, old timer, does the trick voice. Things he can't talk about. You know the story. A bottle every morning, place to sleep it off.'"

No, the vortex that is Tosches' true subject is not even there, though you'd have to be crazy not to want to hear that.

It is, instead, in the way that in song, and especially popular or vernacular song, and especially in the now-you-see-him-now-you-don't mysteries of American vernacular song, voices carry. It's in the way phrases that are at once funny and menacing ("I got a gal in the white folks' yard") travel—and how certain intonations can carry a threat that goes unheard for generations. It's about the way a voice steals a song or, better, the way a song steals a voice. "Some people," Tosches says of Bob Dylan, of Lightnin' Hopkins' 1949 "Automobile" and Dylan's 1966 "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat," "are so cool, so lie-down hip, that they can steal the right breezes simply by breathing... inhale one vision, exhale another. To steal consciously is the way of art and of craft. To steal through breath is the way of wisdom and of art that transcends."

This is where the Emmett Miller story comes to life. Tosches makes this forgotten man a site where dead voices gather: those of the past, those of the present and those of the future, for all, someday, will be dead voices. The field cleared by Miller's odd voice becomes a place where carriers of traditions—so utterly lost that neither the carriers nor the traditions have names—speak out loud. It's a place where, for a moment, one's own place and time seem not fated but a trick played by your own ignorance of where you came from and who you are. Finishing Tosches' book, you may feel slightly ridiculous, as ridiculous as a white man buried in his own skin and now resurrected in his blackface mask.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, September 2001

I liked HELLFIRE, DINO, and (especially) COUNTRY, but I couldn't stand this book. Not because of the subject but because of Tosches's oracular and pious voice. It was like being stuck in a room with a sanctimonious recovering alcoholic. And I found out all I needed to know about Miller from the chapter in COUNTRY.

Greil—I've listened (not recently) to Emmett Miller for 30-plus years, have written about him, and have read a number of works by Nick Tosches. Tosches, his abundant talent notwithstanding, was a writer with, ultimately, a small, very limited tool kit, an individual of emotional imbalance, his "insights," finally, untrustworthy. I would call him a sort of poor man's Hunter Thompson. Re this last: read Dave Hickey's astute essay "Fear and Loathing Goes to Hell" in Hickey's "Pirates and Farmers" collection. As Hickey points out, in Thompson's Las Vegas book, for instance, one learns nothing about Las Vegas, the book's putative subject. "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" could have taken place in Portland, Me. or sunny Tennessee. As with all of Thompson's books, the subject is the author's skillfully, minutely described inner life, which consisted primarily of fear and loathing. Thompson, writes Hickey, was a one-trick pony who "did lyric bile, fear, loathing, and rabid denunciation without much else in his quiver." All this by means of a critique of Nick Tosches. In his book "Country: Living Legends and Dying Metaphors in America's Biggest Music," Tosches takes a look at Jim Dickinson's one solo album, "Dixie Fried." I knew, and truly liked, Jim Dickinson, a good, kind man, for 20 years. I visited him and his family at their home in Mississippi. Dickinson was a fine musician, but what attracted Tosches to "Dixie Fried" was a smallish aspect of Dickinson's talent: a capacity for turning reality lurid, for seeing life's nasty underbelly. Jim was talented, but not a major talent, and when Tosches calls "Dixie Fried" "one of the most bizarrely powerful musics of this century," he is writing not criticism, but pure bullshit. One wants to trust, or energetically engage with, a critic, not recoil from his work in scorn, shaking one's head at how a talented writer could be so damned off the mark.

Emmett Miller was fascinating but ultimately lurid and grotesque, hence what you call Tosches's obsession with Miller. For me, as someone to whom achieving emotional balance is an important task, "obsession" does not describe a particularly desirable state of mind. Obsession is a (mild) form of mental disease; "obsessed" does not describe someone I'd like to spend an afternoon with.