The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Surf's Up, an album to dive into

March 2001

How do you tell a story? Onstage at the Knitting Factory in New York last October, David Thomas, singer for Pere Ubu, this night celebrating the Cleveland band's 25th anniversary with a packed house, threw himself into a performance of big, wide gestures. There was drama, there was melody, there was laughter, there was noise, there was absurdity above all, but the mood was perhaps too good, too bright, for any tale to get told. Yet stories emerge like ghosts on Thomas' new album with his spin-off group, Two Pale Boys (Keith Moline, guitar and electronics, and Andy Diagram, trumpet and electronics): Surf's Up (Thirsty Ear).

"The bellhop in 'Heartbreak Hotel,’” Thomas said recently—the bellhop is the one whose "tears keep flowing," that's all you ever hear about him—"He is the key to everything I've ever wanted to achieve in the narrative voice. The observer who is part of the story and all the while the only real question is whether he knows it or not." That may be the voice on Surf's Up, which so often is spectral, distant, whispering, beckoning you with a finger, staring into a mirror—but another comment Thomas made about "engaging the audience's imagination" may say more about what's happening, or how it happens. What Thomas is after, he says, is something like the moment in an old radio play "in which you hear a creak or sigh and see immediately without verbal description Philip Marlowe's office with dust motes frozen in venetian blind light."

That effect was presumably what Thomas was aiming for on Bay City, the album he put out last year under the name of David Thomas and Foreigners. Thomas used Raymond Chandler's name for the cozy mob town—Santa Monica, really—where he'd send his L.A. private eye to get beat up, but I never felt any sense of place in the music; I didn't hear the creaks or sighs.

They are right there in the first moments of Surf's Up. "Runaway" is just a few lines from a scene from Chandler's 1949 murder mystery The Little Sister—a scene that isn't in the novel, but catches every page of it. A strangled voice tells the little sister her brother Ray's calling—and you know, before you know anything else, that Ray is already dead. The music roars past the story with a tremendous sense of excitement, of engines gunning and then cars roaring out into the desert to get the money Ray left behind.

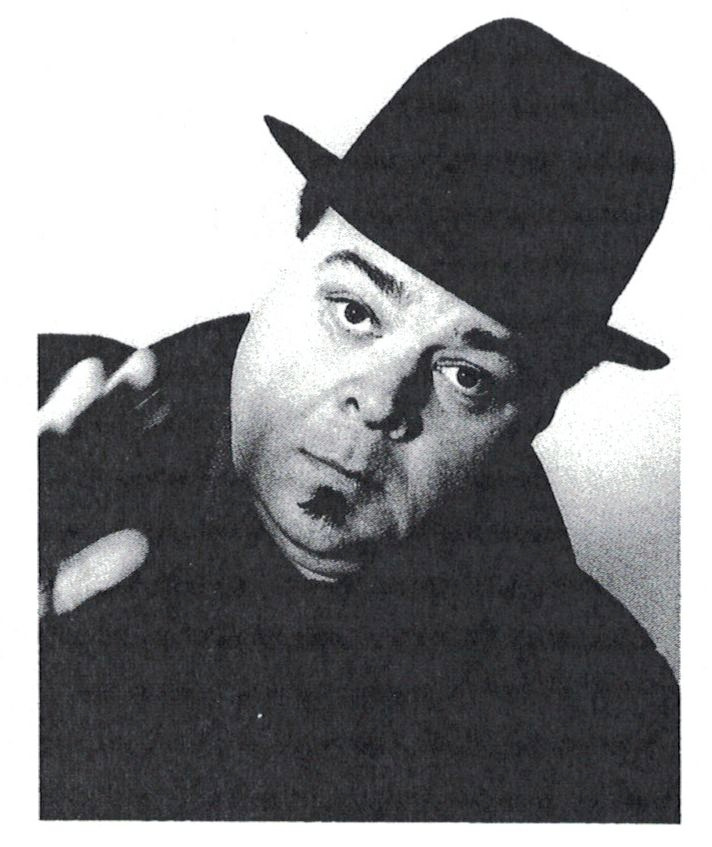

As film noir thrilling as the black-and-white "Runaway" is, the last track on Surf's Up, "Come Home/Green River," all faded colors like the '50s movie stills on the Surf's Up sleeve (a rough, mean-looking middle-aged woman, then the same woman watching with approval as her two strapping young sons fire pistols), is much stronger. Like "Night Driving" ("See ya around, sucker!" Thomas exhales—that's the sigh he's talking about), or "Spider in My Stew" (where the creak Thomas talks about is in the creepily repetitive beat, like an unignorable scratching at a doorjamb, a sound you have to stop, and also a sound that tells you you're better off not knowing who's making it), "Come Home/Green River" calls up an ambience, begins to let a story tell itself. It begins to let you tell yourself the story. Somehow, as you listen, the music, Thomas' voice, the words he's singing, become more and more abstract—but what you're hearing is utterly specific.

Despite what Thomas once said about David Lynch wanting "small-town America to be about weirdness and decay" because it "justifies [his] own life choices," much of Surf's Up could be a soundtrack for Lynch's Lost Highway (1997): a soundtrack so evocative that if the music had come first there would have been no reason for the movie to have been made. But after all the nihilist rushing and speeding of the music that's come before, with "Come Home/Green River," the story has pulled over to the side of the road. The singer—or the listener—has gotten out of the car, to take a look around, to decide whether to go on or turn back. "I know this guy," Thomas is saying in a weird, decaying voice, a voice filtered through a vocoder or something like it, this guy who'd "get in his Coupe DeVille, roll the windows up and drive—air conditioner full blast." It was a question of voices, Thomas is explaining: "he'd drive so as not to hear them."

It sounds like a reasonable thing to do, if you're paranoid, if you never really sleep anymore, if in the middle of an everyday conversation you find yourself thinking of the last election as just that, the last election—and though the album is over, the story you're telling yourself is just beginning.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, March 2001

Dear Michele, send to me and I’ll get it posted. Greil

The 'Runaway' referred to is, of course, Del Shannon's 1961 hit, a song that set Shannon up for life, but also was something from which he could never escape as it followed him wherever he played. I wrote Greil in the Ask Greil column a year or two ago about this sort of Twilight Zone scenario: working musician aspires to stardom and gets it through one song that he must play every day of his life ever after. It was a blessing and a curse. Shannon, long dead and a suicide, no less, and the song itself has lived on and never will die. I guess that's immortality?