This year’s country music heroes pale beside long-gone Dock Boggs

We were driving in the coal country around Norton, an Appalachian mountain town in the southwestern tip of Virginia. The radio was all country music, and it was a bland-out. Travis Tritt, Tanya Tucker, Randy Travis, a crew of smaller names, all of them milking the current formulas of rural references, I’m-your-pal vocals, bright old-timey fiddles, and happy endings—to the point where a snatch of Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Words by Heart” stood out, on a convenience-store cassette player, as an explosion of passion and pain, of reality.

Maybe it was a bad-luck day: There was no Garth Brooks beyond “American Honky-Tonk Bar Association,” a pastiche of everyone else’s songs. No George Jones, just Alan Jackson’s smarmy “Don’t Rock the Jukebox.” “I wanna hear some Jones,” Jackson sang, his phrasing bleeding phoniness, just like everything else he does. The fiddles were the worst. After a bit they were semiotics, not music; nothing was communicated but the sign of traditionalism. It wasn’t simply that one fiddle part sounded like another, doing the same job in every tune. It was as if there were no people actually playing, as if each part came from the vault in Nashville where they keep the all-purpose fiddle sample.

Iris DeMent, with the songs from her new My Life (fiddle on the leaping “The Shores of Jordan” by Stuart Duncan), would have made a difference. Her prim, neat, and fearful warbles, catching the fear of one’s own desires along with the fear of the world at large, would have told a different story. But DeMent’s music, in which traditionalism is only the doorway to a house you have to build yourself, wasn’t just not on the radio, it was nowhere near it. I gave up and stuck a Dock Boggs tape into the car’s cassette player.

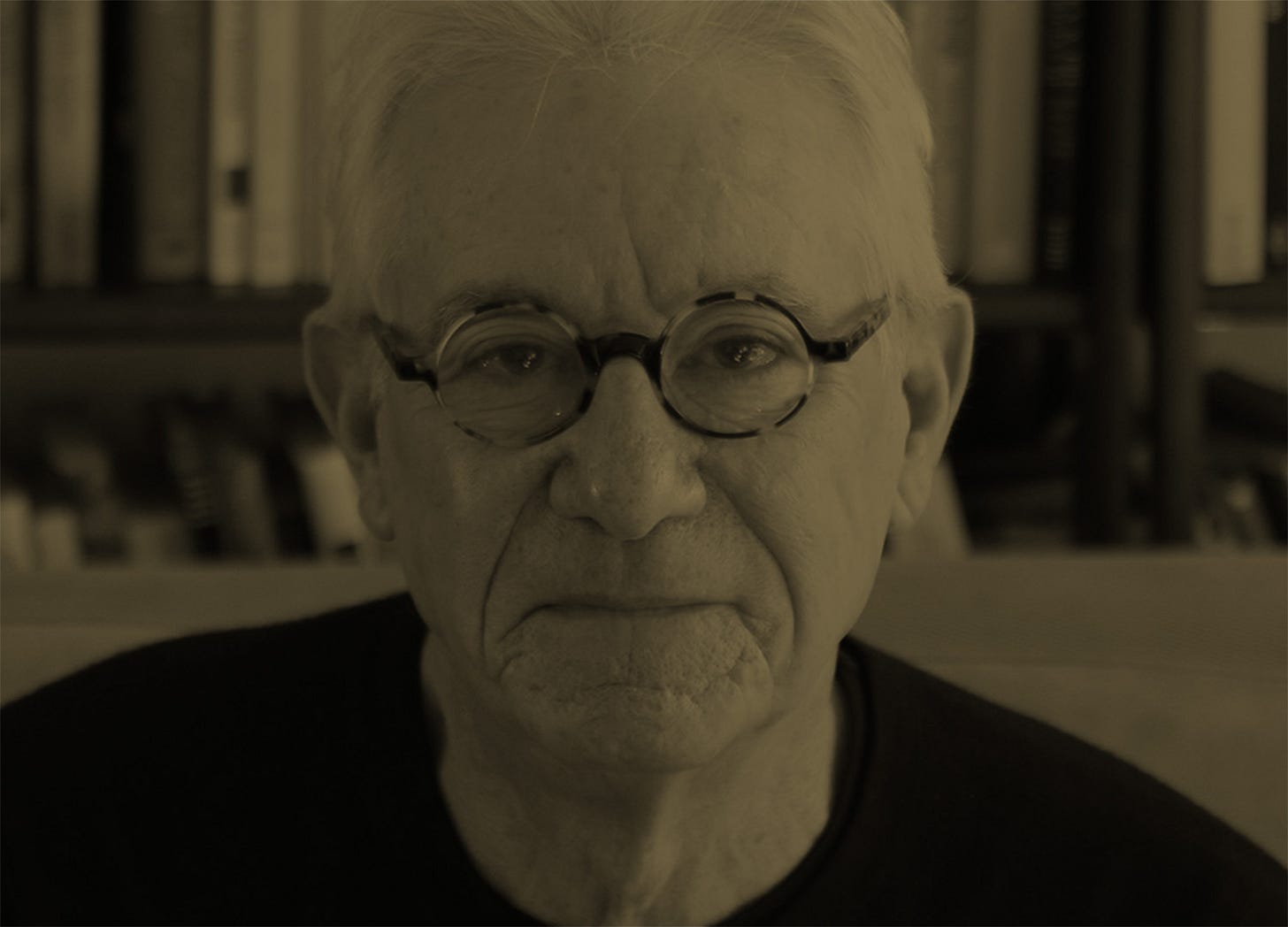

Dock Boggs was born in Norton in 1898. For most of his life he worked the coal mines in the area, save for time as a moonshiner in the ’20s and as a professional musician between 1927 and 1929, when he recorded twelve sides for the Brunswick and Lonesome Ace labels. In 1963, at the height of the folk-music revival, he was rediscovered, right where he’d always been, and went on to record three albums and play festivals and concerts around the country. He died in Norton in 1971. He was—as Thomas Hart Benton had recognized from the first, pressing Boggs’s version of the old ballad “Pretty Polly” on anyone who would listen to it—possessed of one of the most distinctive and uncanny voices the American language has ever produced.

On Boggs’s 1927 “Country Blues” a wastrel faces ordinary, everyday doom. The banjo, which as a white man Boggs plays like a blues guitar, presses a queer sort of fatalism: fate in a hurry. At the close (“When I am dead and buried/My pale face turned to the sun”—Boggs worms you into the old, common lines until you sense the strange racial transformation they hint at), the singing rises and falls, jumps and plummets in a rush, as if to say, Get it over with. In 1963 Boggs recorded “Oh Death”—“Won’t you spare me over for another year?”—and you can imagine Death’s reply, which would have been as fitting thirty-six years before. Sure thing, man, what the hell. It’s no skin off my back. You sound like you’re already dead.

In Norton, I bought a copy of The Coalfield Progress (“A progressive newspaper serving our mountain area since 1911,” the year after Boggs went to work at the mines). It announced a talk at the nearby Clinch Valley College by Sharyn McCrumb, who started out writing comic mysteries set in England and now writes serious, complex, spooky mysteries set in the Appalachian highlands, each taking its title from one of the murder ballads that cling to the mountains like the haze that turns them blue. In the first of these books, If Ever I Return, Pretty Peggy-O, a folk singer is talking to a sheriff about one of the mountain songs, which turns out to be a clue to a present-day murder: “‘It dates from around 1700, but people have always changed the words to fit whatever local crime is current… There’s always a new dead girl to sing about… Isn’t it funny how in the American versions they never say why he kills her,’ she mused. ‘She’s pregnant, of course… So many songs about that. “Omie Wise.” “Poor Ellen Smith.”… So many murdered girls. All pregnant, all trusting.'”

“Pretty Polly” might be McCrumb’s basic text; in its English versions Polly’s pregnancy is part of the story. In Boggs’s version there is, true to McCrumb’s thesis, no mention of it—but there is something more, or anyway something else. The evil in his singing, a psychotic momentum that goes beyond any plain need to do-this-to-achieve-that, overwhelms the song’s musicological history. As Boggs sings, the event is happening for the first time and the last.

Driving around Norton, you can see remnants of a cultural war, between the likes of Boggs’s “Country Blues” or “Pretty Polly” and the churches and signs that dot the landscape: JESUS IS THE ANSWER, JESUS IS WAITING, or, in a hollow, a modest, somehow implacable white frame house, with three stark crosses underneath the words, HOUSE OF PRAYER. Against the lust for escape, for a private exile, that you can hear in Boggs’s songs, the church stood as the nihilist singer’s final temptation, beckoning him to surrender his anger, his refusal, his freedom.

And the war goes on today. Around Norton there wasn’t a song on the radio that would have dreamed of writing a check God couldn’t cash. Except one: High up in the mountains, pressing the radio scanner, Genesis’s “Jesus He Knows Me” turned up. On a pop station and in its video, it’s a cheap British traveler’s satire of televangelists. Surrounded by the piety, reassurance, and easy answers of this year’s country music heroes, though, it was a shock, and as mean as anything in “Country Blues.” “My God,” said the person in the car with me. “What’s that doing here?”

Originally published in Interview Magazine, August 1994

Accurate analysis of the cookie cutter country music scene, and it's only gotten a lot worse since 1994. All interchangeable performers who are frustrated bodybuilders, professional wrestlers, rodeo wranglers, , and Kiss tribute band members. Could easily be reproduced/replaced by AI. At a street festival here in Winnipeg a few years ago I saw a Canadian country artist using a Southern accent not only when he was singing, but also during his between- songs banter. It was kind of funny, and a little pathetic.