The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Where rock 'n' roll secrets can be found

July 2001

One of the best museum shows I ever saw was at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1988—a show about the 1950s. Instead of hanging paintings and displaying artifacts in vitrines, they shoved everything up against walls: art works, newspapers, magazines, household objects, phonograph records, clothes, photographs, movie posters. It was like rummaging through the attic of a whole country. You had no idea what you'd find. The authority adhering to the art was transferred to the likes of the newspapers, and the newspapers transferred their disposability to the art.

The historical exhibits at the Experience Music Project (EMP) in Seattle have that same attic feel. There's no obligation to pay attention to anything in particular and no way to notice everything. The Martian hills of the huge Frank Gehry building are so overwhelming—not only do the shifting colors of the metal surfaces make the building glow, they all but make it move—the structure itself retains the aura that in a museum setting normally belongs to what's on display. You might walk right by even the most mysterious objects: the big wooden door that looks like a totem pole, for example. What is this, you might say to yourself, and suddenly the down-to-earth explanation on a wall card—salvaged from the Seattle club MOE's Mo'Rock'N Cafe when it closed in 1997—is no help. It's still weird. And as a relic of the peculiar kind of music made in the Pacific Northwest from the 1950s on—and it's no matter that it's a four-year-old relic; it looks as if it came from a Kwakiutl Indian fort in the 1880s—the door turns out to be a signpost: an opening into what the EMP calls the Northwest Passage, the richest site in the place. As it tells the best story, it's best to save it for last.

Throughout the EMP there are video monitors for interviews and performance footage, plus speakers with music, making a microenvironment for every exhibit, and you can vastly increase the information on offer with a portable computer guide, or you can just drift and let all the authority that is normally the purview of the object on display reside in your eye: what catches it.

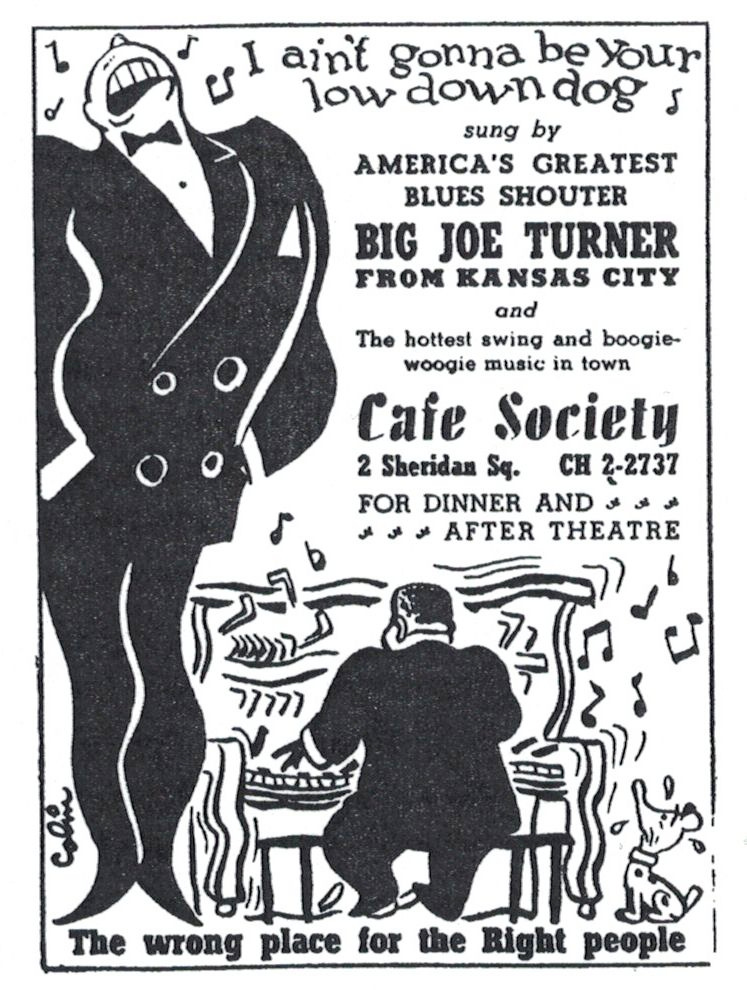

The poster advertising Big Joe Turner at the Cafe Society in New York in 1939 says: "The wrong place for the right people." The picture Muddy Waters had made when, in the early 1940s, producer Alan Lomax finally sent the disc he'd promised would result from the sessions he'd taped in Mississippi: Waters dressed up in his best suit and went to the photography studio in the nearest town to pose with the black 78 rpm pressing in his hand. You look at the picture and you read the letters Waters painstakingly hand-wrote, again and again, politely reminding Lomax of the promise he wasn't keeping.

Everyone's seen exhibits of rock-star costumes; everyone knows how embarrassing they look. But is there anywhere else where you could even imagine coming across the likes of the quintessentially nice-girl beige sweater set worn by Gretchen Christopher of the Fleetwoods ("Come Softly to Me," number one in 1959) of Olympia, Washington? It just stands there, alongside the old 45s, promo photos and press releases it shares space with, nothing to one visitor, shining like the Golden Fleece to another. The Experience Music Project is far more than a history fun house. There are the famous super-high-tech-karaoke sound and video labs, a motion simulator called Funk Blast, a cafe, a bar/cabaret, changing special exhibits. But the fun house is where you can get lost—and find out where you are. Like the MOE's door, Christopher's sweater set is an opening into the Northwest Passage. It's here that the Pacific Northwest, from Portland to Olympia to Tacoma ("Tacoma's like the beginning of all culture in the known universe and nobody seems to realize it," Tacoma native and Seattle punk poster artist Art Chantry says), stakes its claim as the true home of rock 'n' roll: "the wrong place for the right people," or vice versa.

"True home" here means true speech. In the Pacific Northwest—isolated from the rest of the country by geography, its citizens isolated from each other by the weather—the music, so the argument goes, got harder, and it got strange. Clean-cut white high school boys got strange. There were battles of the bands all over the country in the 1960s, but is it even imaginable that anywhere else there was "The Grudge Match of the Year! The Redcoats vs. Mr. Lucky and the Gamblers!" Sure, but "You Are One of the Judges," and "Extra Guards Hired to Keep Bands Apart"? Yes, that's barely imaginable. But "Losing Band to Have Heads Shaved Onstage"? That is not imaginable, not even here. That has to be a Portland urban legend. Except you are reading off the poster: December 3, 1966. Listen to the two CDs of the EMP set Wild and Wooly: The Northwest Rock Collection from Joe Boot and the Fabulous Winds in 1958 to the Murder City Devils in 2000 and it begins to seem inevitable. And you're just starting.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, July 2001

Per a web poster who attended the event, the 1966 "Grudge Match" between the Redcoats and Mr. Lucky & the Gamblers ended in a near riot when it was announced that the audience vote had ended in a tie and no one was going to have their head shaved.