The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Soundtracks for fantasies

December 1996

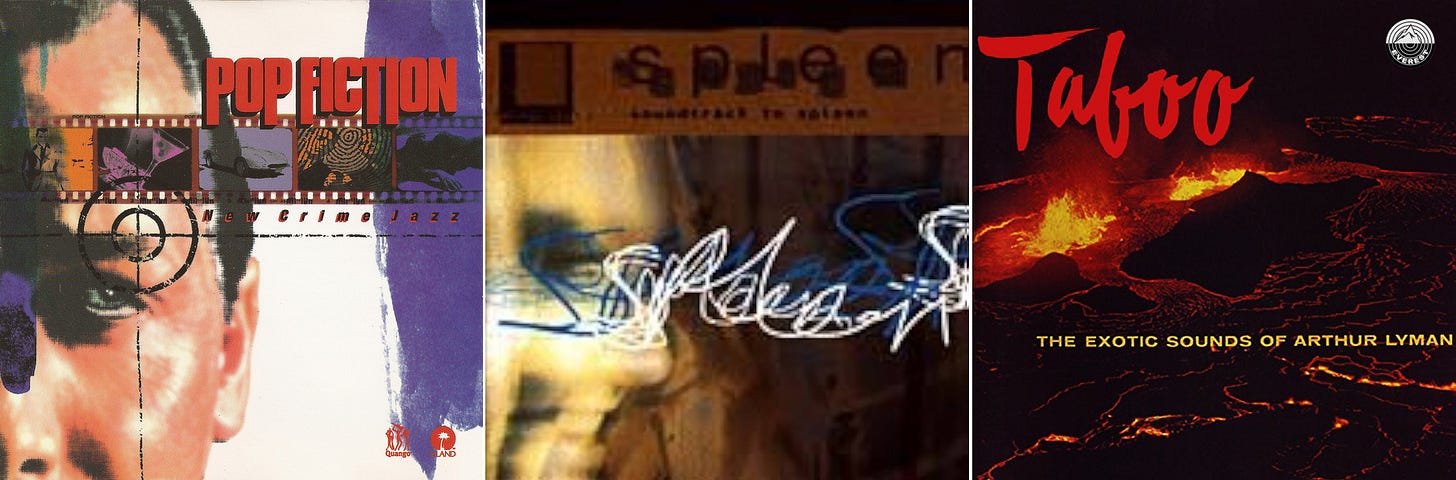

The best section in the record store I frequent—Amoeba Records in Berkeley, Calif., if you're passing through—is the exotica section. This can mean anything from reissues of forgotten (or, better, never-known) '60s surf and psychedelic bands to very white '50s jazz to John Zorn to stripper blues. This stuff at least retains the aura of normality. But surrounding it is material so unlikely, it dissolves all categories, which is to say any possibility of exercising one's taste. Maybe you like surf music. But when it's surrounded by Russ Meyer skin-flick soundtracks, Taboo: The Exotic Sounds of Arthur Lyman ("the album that launched a few million backyard luaus"), turbaned tour guide Karla Pandit's Journey to the Ancient City, Betty Page Burlesque Music, or "groovy suburban wife-swapping party music" (The Sound Gallery, if you really want to know), surf music becomes a kind of social disease. I don't mean an STD, I mean a cultural fetish.

Most of the stuff in the exotica rack you'd never touch, except for whatever it is that's waiting there just for you—the thing your hand reaches for as if of its own accord. The exotica rack is a great swirl of imaginary movies, with the Norman Rockwell–meets–Edgar Allan Poe Gothicism of David Lynch soundtracks hanging over it—a cultural hangover of repulsion with a single, beckoning finger emerging from the ooze. Except for whatever it is you want, you think, "What is all this garbage doing here? How did these old Russ Meyer soundtracks get from yard sales to CDs? Why did they? Is this history—lives once actually lived, luaus once actually thrown, wives once actually swapped—or is it pure abstraction, pure art?" Yes, it's a fact that people went to Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and other Russ Meyer landmarks, but that doesn't mean that anyone bought the soundtracks—or that, in their time, they were even issued. Just because somebody once put out an album of wife-swapping music—assuming this thing isn't some sort of postmodern con—that doesn't mean any wives really got swapped.

It's in this vortex of sub-cinematic mood music—music that seems to relate to films that were never made, but which are implicit in those that were—that you can place some of the most interesting music of the last year: Pop Fiction (Quango) and Spleen's Soundtrack to Spleen (Swarf Anger). Certainly these productions would fit better in "exotica" than in "pop," "contemporary," or "rock." They're all about time shifts; they're all about displacement. They're all about movies you haven't seen but remember anyway.

Soundtrack to Spleen is auteur Rob Ellis's edgy post-bebop chamber music running alongside what I can only call hipster-on-the-run-from-the-bughouse monologues. They start panicky and proceed to complete hysteria, the voice getting scratchier, the notes higher, the horror show more ridiculous. Diva Polly Jean Harvey, on leave from her PJ Harvey band, appears to prove that Lotte Lenya lives, as she slows this imaginary film down and weights it with the heavy breath of age and wisdom. Then madman Ellis is back, trying to convince you that it's all a plot against him—and you might be next! A real stench of the American '50s comes out of this melodrama. Pillaging old poetry-and-jazz records and Commies-in-our-midst movies, Ellis has come away with the smell of fear. As Soundtrack to Spleen ends, he's retching, and out comes the whole panoply of '50s modernism: lobotomies, McCarthyism, Allen Ginsberg's "Howl"—not as the cliché it has become but as the scream of terror it was meant to be. In this movie, it's always dark, the streets are always wet, the hero is always running, and in the end, he pitches out of a sky scraper window for lack of anywhere else to go.

Pop Fiction is my favorite record of 1996; I've played it four or five times a week for months and haven't begun to get to the bottom of it. That may be because it's so hard to get a fix on: Nine current combos, from Portishead to Lou Barlow's Folk Implosion, fool with the textures of '40s film noir, '60s Italian decadence flicks, and '50s–'60s French new wave. They go in arty or they go in cheesy, but they come out cold, still, threatening, lovely, and vaguely unpleasant. The first number, Portishead's "Theme From To Kill a Dead Man" is all foreshadowing—so much that you may feel there's no need to continue: What could live up to this threat? But nothing holds here. Viennese remixers Kruder & Dorfmeister fiddle with Londoner Alex Reece's "Jazzmaster": It comes out sounding like a break in the action in La Dolce Vita, then like all of the action in Last Year at Marienbad, then like wife-swapping music.

As the music suggests dozens of specific films—I can't hear the Portishead piece without falling right back into Louis Malle's Lift to the Scaffold—it pulls away from all of them. The music drifts into a half-familiar theme, stops, drifts toward violence, shies away, gives you the hint of an image: a couple in bed and someone, maybe you, watching. What you can identify, what you can name and categorize, what you can take out of this weird exotica section and put in a nice, organized, decent category—the presence of Twin Peaks in Beanfield's "Charles," say—is comforting, but only for a moment. The abstraction in the music—the feeling that it is being made by a certain floating sensibility, not by individuals with names and bodies—is overwhelming, and a pure pop thrill. Betrayed lovers, hired killers, torturers and victims, grinning psychopathic psychiatrists, and trusting wives raise their heads out of the sound, but only to invite others in. This is music in service of memories the musicians know are out there, somewhere: exotic because it is not real, yet so compelling because, to the degree that culture makes history, it is real. Pop Fiction's unmade movie traps you in movies you've already seen, in the life you've already led.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, December 1996

I remember this section so well at the Towers where I would shop in D.C. and Waterloo Records in Austin. Great great stuff! Just looking at the covers and reading the song titles was enough. It was easy to spend an hour just looking through them all, and then wondering, Who is gonna by all this shit?