Donovan: There’s No Hipster Like an Aging Hipster

People called Donovan a genius, but nobody ever said he was smart. Hear him in his heyday in 1967, still warm from the Summer of Love, in the pages of the first issue of Rolling Stone: "We are magic. It is magic that we're walking around…" "You're a rarity and you're aware of it," says the interviewer, with nice internal assonance. "Yes, I'm very aware of this," Donovan says. "Yes, the more aware I get the more I can understand how big it is, how big it'll get... To say to somebody that God is everything that lives and that ever has lived and... "

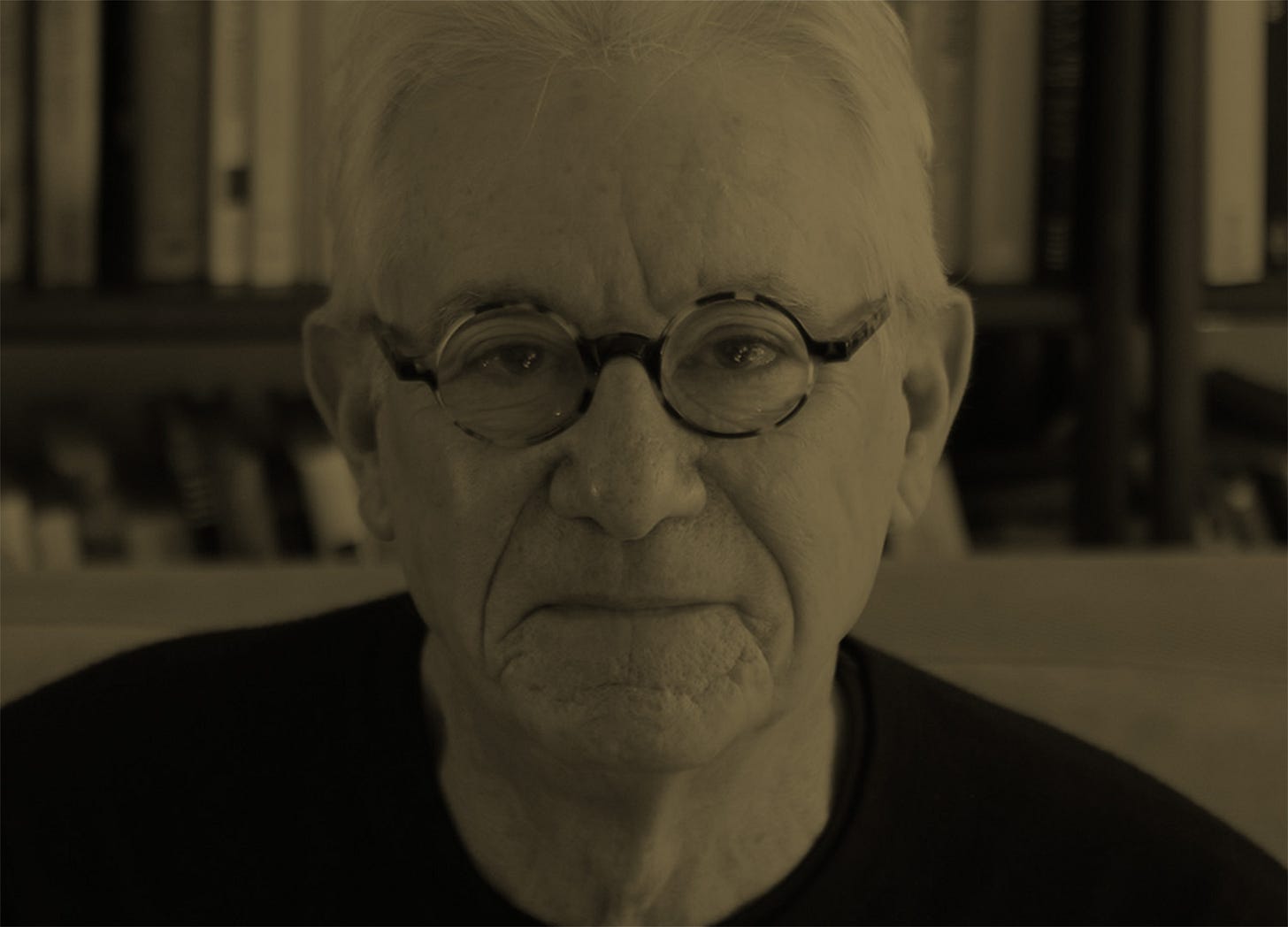

He sounds little different today, a forty-six-year-old grandfather who perhaps most often gets his name in the papers as the father of actors Ione Skye and Donovan Leitch. "The heartfelt longing to discover the truth within," he burbles in the notes to Troubadour: The Definitive Collection 1964-1976 (Epic/Legacy), his new boxed CD set (everybody gets one these days). "This quartet of movements in my life I attribute to four powerful influences," Dad, Mom, Wife, and "In praise, I raise my voice to the great and glorious spirit... "

Yeah, right. Can't argue with that. But you can argue with Troubadour. The whole sounds so depressingly time-bound, inert—while his two signature albums, Sunshine Superman (1966) and Mellow Yellow (1967), remain full of generosity, curiosity, play, and surprise, leaping into a future that vanished almost as quickly as it came into view. For all the story-goes-on lilt of the essays in Troubadour's requisite illustrated booklet, the discs mainly remind a listener of how neatly Donovan can be summed up—which is to say, even though he is performing today, dismissed. Donovan had his first hit single in 1965 and his career as a pop icon was wrapped up by 1969. He was a Scottish Woody Guthrie transformed by the smoke and mirrors of Swinging London into a visionary in caftans, a flower bearing gifts for your garden—and then the pop world turned its back on him as one. Go away! Please! Don't embarrass us! Don't you know it's 1970? Pop fans were embarrassed by Donovan's fey silliness, but also by the shame they felt when the promise of their time, a promise he and they had shared, failed to be realized in real life. It may have been Donovan's essential dumbness that allowed him to fulfill that promise in a few of his songs, a spinning handful: "Season of the Witch," "Guinevere," and "The Trip" (all included on Troubadour), "Legend of a Girl Child Linda," "Celeste," "Young Girl Blues," "Hampstead Incident," and "Bert's Blues" (not included, but available on various single-CD reissues). Invited to a '60s party that was never going to end, that guaranteed more glamour and wonder every time you turned your head, Donovan didn't think, he just opened his eyes. Unlike Bob Dylan, skulking in a corner, doubting everything, Donovan doubted nothing. He was going to go all night.

You can hear this best in "Bert's Blues," from 1966, as good a proof as any there is of the right of pop music to do whatever it pleases. It's an all-night party, but now it's about 4 A.M. Some of the revelers have fallen asleep, the rest are happily halfway to oblivion. Someone starts singing. It's an odd, off-the-mark hipster shuffle, jazzed up, hilariously fake, the singer's diction clipped and stilted. He doesn't say "It ain't for me to say"—he says "lh t'aint for me." It's pure narcissism. He's in love with the sound of his own voice, with the way he can play with it, and just as you're laughing at the pose, you're charmed. But what's that harpsichord doing—playing blues? With utter grace—a natural shift, somehow—the song is swept away. A cello comes up, and now it's as if the singer has nodded off on his feet and you're dreaming his dream. Something about fairy castles, kings, queens—flutes and more strings finish the scene with chilly elegance. A sense of privilege, chivalry, nobility—a sense that you are privileged to be present in this moment, even though it is your right of birth—settles on the room. The cello rises, pursuing a minor chord, signifying doom, or danger, anyway. "Sadly goes the wind on its way to Hades," the singer's dreaming voice says; you don't believe him. But then there is only that harpsichord, moving with stately slowness through a harsh, severe solo. The cello and the flutes return, the singer says, "Lucifer calls his legions," and now you do believe him. The music seems to draw a breath, and in that tiny suspension the music is swept back to its opening theme: blues again, but harder. You're in a jazz joint in Soho, the hipster is back, there's a lot of noise, the harpsichord is wailing (the harpsichord?). You finally stumble home, fall asleep, dream—and what you dream is what you heard. You wake up: where, you say, have I been? Can I get back?

The answers "Bert's Blues" gives are these: where you were, was in the middle of a Pre-Raphaelite painting, in Edward Burne-Jones's The Tree of Forgiveness or The Beguiling of Merlin, in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Beata Beatrix or a thousand cheap knockoffs of the like. You were in a state of grace where there was no noise, only a dance of seductive gestures, an instant before desire overcame all fear. And can you get back? Of course you can, because the past is in the present, the present opens up into the infinite past. Time is a trick you need no longer play on yourself. You can be whomever you imagine yourself to be: Soho hipster, Arthurian maiden, '60s pop star.

You can still hear the bare leavings of this—not an idea, but a sensation—in "Season of the Witch," Donovan's most piercing, most indelible recording. He looks in the mirror: "So many different people to be," he says. But the rest of the tune—cut up with unfriendly guitar chords, rumbling organ, and terribly hesitant, uncertain movement—somehow turns the face of Beata Beatrix from the instant before ecstasy to the instant before murder. The song sounded funny in 1966: "Beatniks out to make it rich," what a laugh. Now, though, you hear the reveler awake in his hangover, shaking: "You got to pick up every stitch," he says again and again, but he can't even pick up the coins from the floor. He can't close his fist around the nineteenth-century Arthurian cultural detritus that in 1966-67 flared up like new clothes.

Donovan didn't think, but he drifted through the signs and symbols that were common coin in his time. Because he had the sense that those signs and symbols were very old, the best songs he made of them are now no more tied to the time of their making than Pre-Raphaelite paintings are to theirs. So, oddly, the weird shifts in "Bert's Blues" now sound less contrived than those in the Beatles' "A Day in the Life" (which "Bert's Blues" predated by a year), and "Season of the Witch" sounds as mean as Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone." All are at least a quarter-century old, but none has ever been off the radio since it was made, save for "Bert's Blues," which has never been on it.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, November 1992.

I have a fantasy that Donovan is in a cutting contest with Them-era Van Morrison and is getting his ass handed to him until he pulls out "Season of the Witch." He wins by acclimation and is given a crown of roses by a unicorn.

I’ve always liked Donovan and always felt a bit embarrassed about liking Donovan.