The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Pop going places it never went before

July 1996

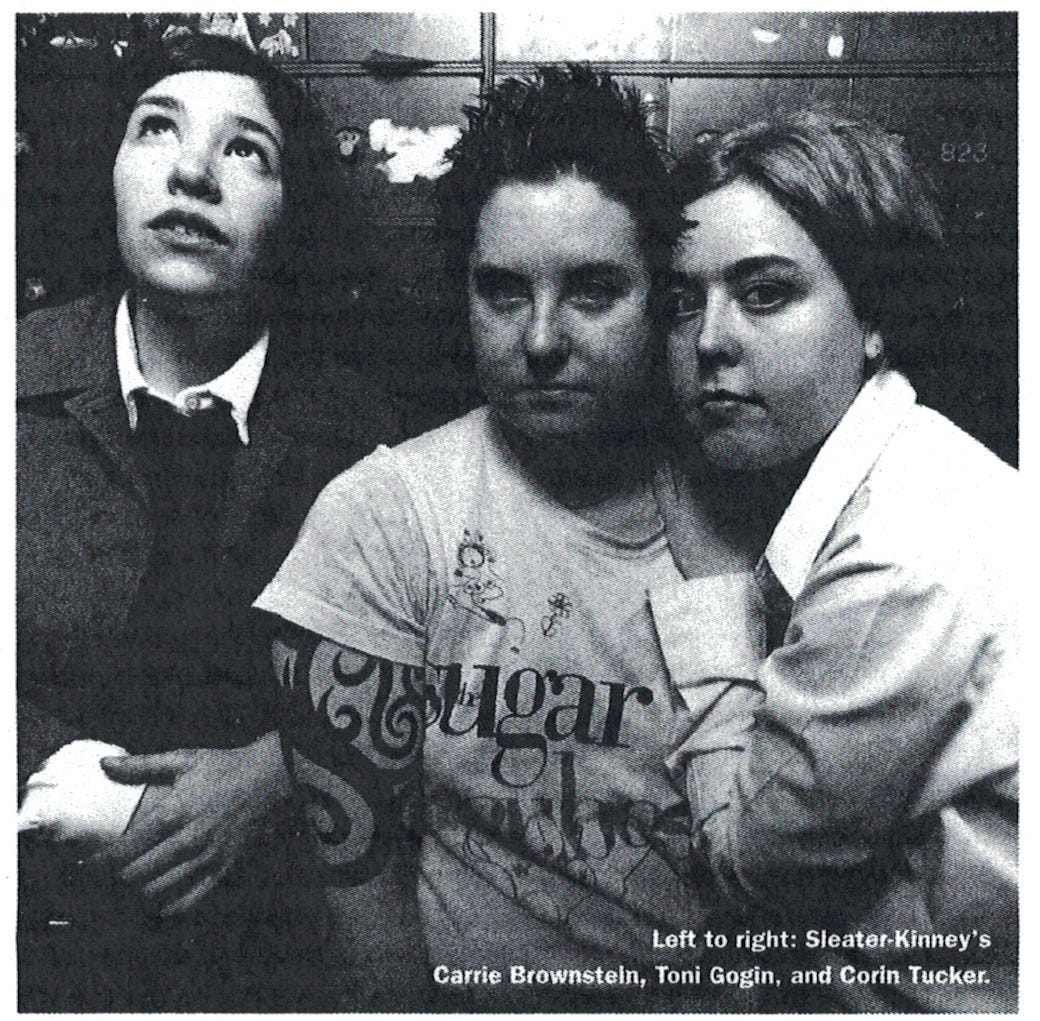

"Just wanted to drop you a line, post-Sleater-Kinney onslaught," my friend Lisa Bralts of Cargo Records wrote on April 25, after the Northwest trio finished the Chicago turn of its first national tour. It was a get-in-the-van odyssey that saw guitarist Carrie Brownstein of Olympia, Wash., and guitarist Corin Tucker and drummer Toni Gogin of Portland, Ore., perform in punk clubs, record stores, college spaces, a church, and a sushi bar. "They played two shows here + both were good. Tuesday night's was a free show at the Fireside Bowl, a bowling alley-cum-punk rock venue whose seediness is unmatched by any other venue I've been to (fluorescent lighting, stained dropped ceiling, the smell of cigarettes/beer/feet dating from the mid-'60s. . . ). There were about 100 people there, mostly 18 + under riot grrrls + the queer punk youth who seem to live at the Fireside. Everything got underway late, which may have added to their complete FEROCIOUSNESS. . . the sound system was crap but they overcame it. Still can't believe Corin sings that way every night. . . "

I can't believe she doesn't. In the two shows I've seen Sleater-Kinney throw at small, rapt crowds over the past year, the power in the combo was so stark, so focused, it seemed most of all implicit—as if they weren't using close to all they had, just what they needed. Certainly they were stronger this March 21 at the Bottom of the Hill in San Francisco, with Gogin, than at an earlier show in the same shelter-in-the-storm spot with original drummer Lora Macfarlane. It was only the second show of the twenty-five-city tour, but the band had its new songs from the shocking Call the Doctor (Chainsaw), its second album. As on that album, within seconds their music was complete.

As is proper and pro forma in a small punk club, Sleater-Kinney come onstage and fiddle and tune with the approximate glamour of people sweeping the floor; then, with a vague sort of apology at the necessary separation performance puts between musicians and audience, they begin playing. But I've never seen such a leap in such a moment. Corin Tucker shuts her eyes—scrunches them shut—Carrie Brownstein starts moving her arms and legs, and instantly the noise they're making seems abstracted from their mouths, fingers, bodies, instruments. It seems much too big, too much in motion: Onstage three people are drawing a diagram of the big bang, every particle of the universe flying away from every other, but in the audience a diagram is the last thing it feels like.

On Call the Doctor—what a title for a piece of music that means to call everything into question—you can hear this moment in any of the first five songs: the title tune, "Hubcap," "Anonymous," "Stay Where You Are," but most immediately in "Little Mouth." Two guitars make a pulse, and Brownstein floats two words on it: "Damn you!" she snaps, and you feel the song take its shape. In fact you've been set up. "DAMN YOU!" Tucker shouts back, and you're in a larger realm, more dangerous and far more promising, a place where it feels as if anything can happen. "I'm your monster, I'm not like you," Tucker sings in "Call the Doctor," nailing each word like Sondra Locke's knife thrower in Bronco Billy. You believe her. But in "Little Mouth" you do want to be like her—you want the pure emotional lucidity the performance grabs and holds.

The whole song—maybe that entire relentless first sequence of cuts on Call the Doctor—could derive from a single moment in pop history, one of the most perfect: Chrissie Hynde's clipped "fuck off" on the Pretenders' "Precious." That was 1980, when the women in Sleater-Kinney were little kids; it's their heritage, their birthright, they are the legatees of the moment, and they make the most of it. You can hear much more that's vaguely familiar in Sleater-Kinney: the great Zurich punk band Liliput/Kleenex in the squeaks and yelps of "I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone," the Gang of Four in the speed of Tucker-Gogin-Brownstein's negotiation of their own hairpin turns, the Go-Go's in the chorus of "Hubcap," Tucker's previous group Heavens to Betsy in the bedrock seriousness of the singing, Sheryl Lee's face in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me in the dark corners of every story Sleater-Kinney tell. But as for what really goes on in Sleater-Kinney's music, no one's heard this before.

With the confidence Brownstein uses on the phrase, her "damn you" is far more complete, more final, than Hynde's "fuck off"—not as thrilling, maybe, not as sexy, but harder. But Tucker—a twenty-three-year-old who comes onstage looking like a shy, sweet-faced girl playing hooky from her Catholic high school—has a much bigger voice than Brownstein, or for that matter anyone else currently practicing pop music. With a steely passion channeled through the affect of her all-American-mallrat accent, she starts off at high pressure and stays there, the tension of her refusal to press any harder turning into a nervous worry that she might. Against this, the fabulously engaging interlocking guitar lines seem more found or received than made—the deep inventiveness of the band coming off simply as the necessary consequence of a voice this demanding.

Tucker's rocket launch of "DAMN YOU" immediately puts the words, their sound, into a different world than the one Brownstein uses them for. Here the words are so enormous it's no mere person who's their target—no mere person would be worthy of words this enormous. The words—the breach they make in space and time—include you, include the singer, and everything in between. They close nothing off; they don't say, "Shut up." They say, "Speak this language, if you can."

Sleater-Kinney shoot this challenge out in so many ways, riding it with such fervent pleasure in song after song. That's why I can't imagine Corin Tucker doesn't sing that way every night. Perhaps more than any band before them, Sleater-Kinney are all or nothing, and I can't imagine nothing coming out of her mouth.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, July 1996

Loved seeing this reappear online.

Yeah, it was the "hard" part; their singular hardness. They were harder than any macho man hard rock. The Riot Grrl answer to Nirvana. Less Dinosaur rock, more post-punk. Kleenex/Lilliput! Also Kim Gordon's SY.