The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Cranes and Cranberries

October 1993

Transcendent Dream Pop

Dream pop can mean English groups like Lush or the Sundays, who I can’t listen to, My Bloody Valentine, who I’ve walked out on, the Cocteau Twins, who I’ve never understood, the Cranberries, from Ireland, or the Cranes, who these days I dream about. When the music works, it’s first of all seductive; there’s a relentlessness in the Cranberries’ “Dreams,” in Dolores O′Riordan’s reveries as she thinks about her lover, that can make the singer’s nearly absolute sexual distraction your own.

I don’t know if dream pop is a style so much as a sort of dropping of one’s guard, but here a female voice floats free of all other elements of a performance: lyrics, instrumentation, the singer’s looks, fashions of clothes or makeup. If the voice can truly move, it becomes self-referential, as if seeking its own, self-contained language. The words that make up normal conversation are just sounds, and other people in the songs come to life only to the degree that they reflect the singer’s light. Voices tend to be high, and in pop music, a high female voice usually communicates innocence, or dumbness. In this music it seems to summon the landscapes and poses of the Pre-Raphaelites, where our Christian ideas of innocence and our Enlightenment notions of intelligence break down into paganism.

I like to think dream pop begins on the cover of Kate Bush’s 1982 album, The Dreaming, where you gaze at a handsome man with severe, cruel features. He’s in formal dress; he’s got some kind of block-and-tackle apparatus, some sort of bondage gear, draped over his shoulder. In his embrace, but with her face pointed away from him is Kate Bush, beautiful, of course, but with a wild expression on her face. You can’t read it, because it won’t hold still: one moment it’s fear, the next lust. But all this, which you glimpse in an instant, is barely more than a frame for the heart of the photo, which is so odd you don’t register it right away. Kate Bush’s mouth is open; on her tongue is a tiny, perfect, glowing gold key. Never mind the music inside the album: that is dream pop.

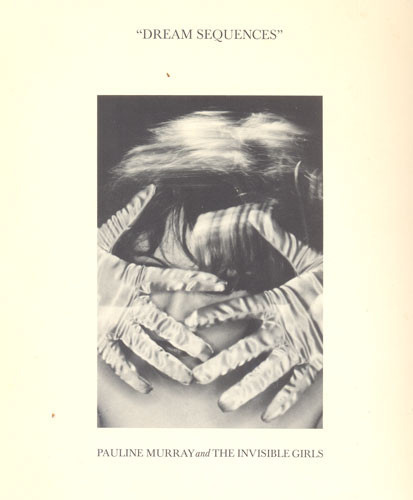

In truth, though, you can find gropings toward the form as far back as the Jamies’ “Summertime, Summertime” (1958) or Rosie and the Originals’ “Angel Baby” (1960), and in modern terms dream pop begins definitively with Pauline Murray. She appeared in late 1976 as the singer for the English punk band Penetration. The 1977 “Don’t Dictate” was a pure punk single, but Murray always winked; she didn’t find her voice until 1980, with the just-reissued Pauline Murray and the Invisible Girls (Polestar). Here, punk escapes itself, it goes elsewhere, into a utopia, a nowhere where freedom is taken for granted, and beauty, too. All through the album Murray radiates release; on “Dream Sequence 1” she slips all around her past and future. Her voice isn’t a good one; in its happy way, it’s still a punk voice, straining on the high notes and floating melodies. Murray sounds almost as embarrassed as she does proud when she sings of “my naked body,” but now everything about her is exposed. She doesn’t care: “Now I’m crossing/The bridge of conscious.” The voice is not in the least professional. After years as the instrument of a failed pop star, it is still completely ordinary, but it knows what it wants. It wants transcendence, and the very ordinariness of the voice that sounds the plea makes transcendence seem accessible to anyone.

On Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? (Island), the Cranberries’ music is easy to hear—shimmering, with drummer Feargal Lawlor playing just behind the beat, as Mick Fleetwood did in Fleetwood Mac. “Dreams” is an almost perfect hit record; you know it the second time you hear it. But because the Cranberries are as expert in anything they do as Pauline Murray was clumsy, they fall short, or stop short, of the sense of the uncanny that animated her music. Their music can be contained by the radio, by whatever plays on either side of it.

I haven’t heard the Cranes on the radio, but I can’t believe this would be true with them. Singer Alison Shaw doesn’t sound remotely like Pauline Murray, except in the heart. Her voice isn’t high but tiny, compressed, scratchy, disturbing; all you know for sure is that the reality it’s describing isn’t a waking one. It’s no nightmare: the pace is slow, measured, deliberate, yet drifting. The band formed in Portsmouth, England, in 1988; a first album, the 1991 Wings of Joy, was a curio. Forever (Dedicated/RCA) is closer to a disease.

Alison Shaw sounds like a little girl who’s lived her whole life in the closet under the stairs, sometimes scratching at the door. Such a voice—and the gestures of the entire band, guitars, bass, drums, piano—is in no hurry, because there is no time. They’ve got all night and there’s no promise of waking. Oftentimes Shaw doesn’t so much seem to sing as breathe—to breathe her words, which don’t exactly communicate as any kind of English. Whatever the songs are literally about, unlikeliness, doubt, uncertainty, and calm seem to be the actual subjects of the music—all in all, an embrace of a certain fatalism.

It’s the fatalism, if that’s what it is, of modern European doppelganger movies—the hallucinatory sweep of Ildiko Enyedi’s My 20th Century (1989) or Krzysztof Kieslowski’s vaguely supernatural but less magical The Double Life of Veronique (1991). In these films a sense of the instability and unfixedness of individual identity—an instability that’s both tragic and luminous—has replaced the social instability, the specter of conspiracy and double agents, of the old European spy movies. If the spirits in the Cranes’ music are the spirits of the world taken down to its primary elements—individual women and men who themselves don’t know who they are—then the music may speak for a world in which social bonds, and concepts like patriotism or community, have utterly disappeared; the music may also speak for a world in which everything bigger than a woman or a man has to be reinvented from scratch, and will be. Or it could simply be a dream and you’ll forget it in the morning.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, October 1993

Not my dream pop faves, by any stretch, but expressions of female desire sounds about right, and the historical perspective, Pauline Murrray and Rosie & the Originals, insightful. Reminds me some of Simon Reynolds' talk about 'oceanic' feminine feelings in dream pop, around about the same time.