The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: The Alarm Bells Pop of Come and Sarge

July 1998

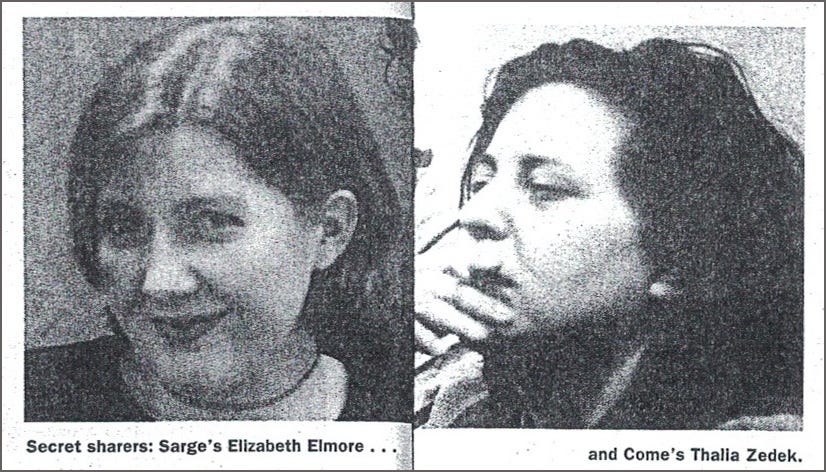

Thalia Zedek is in her mid-thirties. She's been making records since 1980; after time in Uzi and Live Skull, she now leads the Boston guitar band Come. Elizabeth Elmore is twenty-two. She's been making records since 1996, and leads the Champaign, Illinois, guitar band Sarge, her first. But both women seem much older than they are, as if they've already been through everything twice. Elmore gives you the idea the third time might be different; Zedek doesn't.

Zedek's voice is weathered and rough, her guitar playing a manifesto that might be arguing for the implacable and the inexorable as the source of all values. On Gently, Down the Stream (Matador), Come's third album, the music Zedek makes with co-guitarist and sometime singer Chris Brokaw is all black storms and dead-of-night misery, a train they're jumping just because, unlike everything else in the world, it's not standing still. The result would be impossibly corny if Zedek and Brokaw's commitment to this story—which comes off not as an account of disasters already lived but of all those that remain to be lived—wasn't so fierce. Zedek reminds me of the photographer Nan Goldin—with Goldin having just installed the latest version of her "Ballad of Sexual Dependency" and wondering if it's worth it, wondering why it is that her pictures still shock anyone. Can't people see what's in front of their fucking faces? Why do they need me to show it to them? I showed them "I'll Be Your Mirror." I'll be your fucking mirror, and then I'll fucking break it.

Elizabeth Elmore's voice is girlish and cutting. It seems even higher on The Glass Intact (Mud), Serge's second album, than it did on Charcoal, their blazing, bitter debut. Zedek's and Brokaw's guitar dramas are about twists and bends and drones, about stories whose beginnings are as fated as their endings; Elmore's guitar playing is about angles and flurries of noise, about obstructions that trip you up or sharp turns you make without thinking. With Come, instrumentation and singing and words are all of a piece. With Sarge, the resignation or hate in a lyric, or in Elmore's delivery of it, can be cut up by the energy and delight of a young band discovering what they can play. While Come are drawn to the Gothic possibilities Led Zeppelin left unexplored in "Stairway to Heaven," or that nobody but the Beatles—or Zedek—heard in "I Want You (She's So Heavy)," Sarge play swift punk, like Amelia Fletcher's band Heavenly or the great '80s group Altered Images.

You never know when the apparent pop song Sarge are playing will turn cruel—when the fun of their music will come clean, when the fun will turn out to be a matter of softening up someone in the song for revenge. Elmore keeps you guessing, and she can make you nervous. "I Took You Driving" is a hedged seduction song that turns out fine. But on The Glass Intact so much violence and loathing have preceded this nice tune that it might seem like a setup. You might cringe, as if rape or murder could follow Elmore' sweet come-on. She shares attitude—a sonic version of X-ray vision, the sidelong glance that looks right through you—with Corin Tuck er of Sleater-Kinney; she feels more like Joanie Sommers singing "Johnny Get Angry" in 1962. I hear Elmore walking into Zedek's show with Sarge drummer Chad Romanski and bassist Rachel Switzky, into Zedek's version of Nan Goldin's exhibition, having no trouble recognizing herself on the walls, but finding all the photos garish and hyped up: Don't you think, she says to the rest of the band, that it's all sort of romanticized? It's a show she can read like a comic book.

That's the privilege of youth, to find old people like Zedek morbid, obsessed with death, with the death that year by year can seem ever more present in life: singing in Come, Zedek is sexy like Isabella Rossellini is sexy in Blue Velvet; when Elmore flips out a memory of "You slipped your hand underneath my dress," she's completely teenage, for a moment as soft a touch as Megan on Melrose Place. Still, there are ways in which Sarge are chasing music Come have already made.

In 1994, Come called their second album Don't Ask Don't Tell, and then they proceeded to live up to the title. Not a song into the record, the phrase that entered the language as stupid and humiliating became spooky and dangerous. As if keyed by lines from Bob Dylan's "Outlaw Blues"—"Don't ask me nothin' about nothin' / I just might tell you the truth"—the music really did seem full of secrets: secrets that couldn't be told, only affirmed. That quandary is like a first premise on Gently, Down the Stream. Secrets can be told only in the dark, but even as "Recidivist," "The Fade-Outs," "New Coat," and "March" build on each other with force and conviction, Come can never make it dark enough. Zedek stands in an apartment flicking the light switch again and again, and the lights never go off.

In Sarge's music, secrets get told straight off. They can be ugly and terrifying, as with "Chicago" on Charcoal, or deliciously lustful, as with "Fast Girls" on The Glass Intact ("I-met-this-girl-at-a-Madison-punk-rock-show-she-made-fun-of-all-the-boys-from-my-hometown," Elmore blurts, trying to keep up with the going-nowhere-faster beat of the band, and just that fast you're at that show, too). But here the secrets don't last. They don't build on each other; they don't accumulate. The woman singing doesn't seem to carry them with her. With Zedek, each song she sings is like a new suit of clothes she'll never be able to take off.

They'd make a great double bill, Come and Sarge. Listening to their records, you can almost hear it, or see the music of one change in the face of the other.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, July 1998