The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Velvet Underground

September 1993

Velvet Underground, back from the grave

This June I was in England and Germany, giving readings and lectures. The first thing people wanted to talk about was the Velvet Underground reunion tour. By a quirk of scheduling I was chasing the band around the EEC, missing them by a day in city after city. Everybody who asked what I thought had just seen the group, in Edinburgh, London, Hamburg. Nevertheless they seemed to want permission to like what they'd already seen, or for that matter already liked. Was this—retrograde? If you could still have fun with the Velvet Underground, was that proof that time had passed you by?

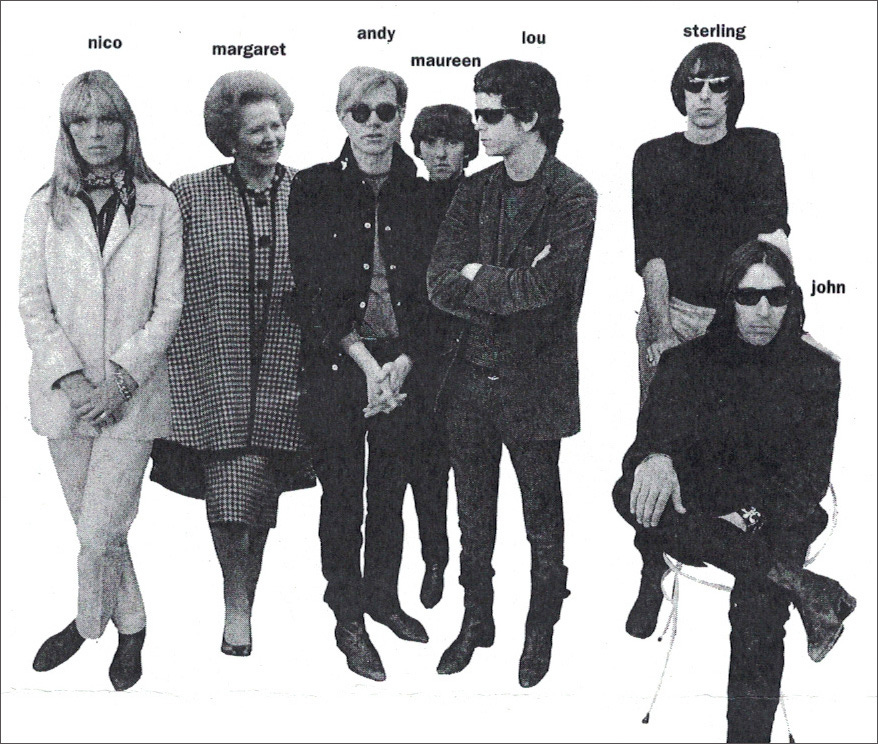

It had been a neat quarter-century since bandleader, guitarist, and composer Lou Reed kicked bassist and violist John Cale out of the group. Formed in 1965 and soon coming under the aegis of Andy Warhol, who for their first album forced German chanteuse Nico on Reed, Cale, drummer Maureen Tucker, and guitarist Sterling Morrison, the band was defunct—no matter who the players were—by 1970. But even before any formal ending, the Velvet Underground had been a legend—of freedom, extremism, self-destruction, rebirth, to-thine-own-self-be-true, of art. The legend had long since overshadowed solo careers, or even lives. Or history. As one Garth Marat-Trech proved in 1992, in The Wire, reviewing Margaret Thatcher's spoken-word disc Salute to Democracy (no kidding—it's on EMI Classics), beyond a certain limit a good legend has room for absolutely everyone and facts are utterly beside the point.

Margaret Thatcher, the enigmatic conceptual artist, is probably best-known to the general public for her series of "action music" pieces, which "detourned" the mass rallies often associated with totalitarian regimes, but her talents have been deployed in many fields over the years. Legend has it that in about 1963, quitting an early lineup of the Velvet Underground (she played electric violin; Henry Flynt was her replacement), Thatcher effectively retreated from the art world: "There is no such thing as society" became an in-joke at Warhol's Factory (often diluted with typical loft-apartment humour to "There is no such thing as Andy Warhol" or "There is no such thing as Margaret Thatcher").

The legend had other facets, perhaps most gleaming that avant-garde standby "fleurs du mal," more popularly known as evil. Ages ago, The New Yorker used to run cartoons of dumpy, middle-aged couples sitting around their middle-class living rooms: "Darling," the woman would be saying, "they're playing our song!" and coming out of a radio would be "You ain't nuthin' but a hound dog" or maybe "Da doo ron ron." Whether or not the Velvet Underground bring their show back to the U.S. this fall, there will be a new live album, and likely a new middle-aged New Yorker couple mooning over "Heroin."

The Velvet Underground and Nico, the band's first record, is nowhere near so striking as legend has made it out to be. Most of it sounds exactly like 1967, as time-bound as fashions from Carnaby Street. But "Heroin" is still pure terror. The song opens up a void, and one hand beckons you in, because there are secrets here you'll never learn any other way; the other hand dismisses you, because you're not strong enough to know those secrets. The song is evil because it celebrates death and apologizes for nothing. The fatigue, the weight in Lou Reed's voice at the very end, the flat refusal to explain himself for one word more in the last "I just don't know," are unlike anything else in modern culture, unless it's the way Jean-Paul Belmondo falls down dead at the end of Breathless.

I'll never forget the first time I heard the song. I was a college student in Berkeley; the tune was on the radio. I wanted to turn it off, but I couldn't. Near the end, when Maureen Tucker stops playing and Reed and Cale crisscross lines of sound so crazily it seems certain the piece will dissolve in the air, you can almost believe the song doesn't mean what it says. Then Reed comes back and, with an irreducible subjectivity—an affirmation that he and no one else is telling you the way the world looks to him—nails that last line.

"That was the Velvet Underground," said the disc jockey, the late Tom Donahue. "A very New York sound. Let's hope it stays there." What did that mean, outside of simple snobbery? Maybe this was only art—New York art, but not life. Experience is overrated in art, after all; empathy is the test and imagination is the judge. Writing in 1965 to Delmore Schwartz, his first mentor, Lou Reed himself sounded like a tourist:

I've had some strange experiences since returning to ny, sick but strange and fascinating and even, sometimes ultimately revealing, healing and helpful. . . ny has so many sad, sick people and i have a knack for meeting them. they try to drag you down with them. If you're weak ny has many outlets. I can't resist peering, probing, sometimes participating, othertimes going right to the edge before sidestepping. Finding viciousness in yourself and that fantastic killer urge and worse yet having the opportunity presented before you is certainly interesting.

Or not like a tourist: "Interesting," he wrote next, "is not the word."

The first challenge Reed, Cale, Tucker, and Morrison faced in June was to get out from under this sort of legend—to reclaim their subjectivity from it. Audiences were expecting them to burst into flames onstage. Playing legendary songs, they had to find a way to do so prosaically, for prosaic reasons—to have fun, to make money. From all accounts they were able to do that. "The crowd was very young, and the place wasn't nearly full," said a photographer in Hamburg. "I don't know what they wanted—I don't know what I wanted. They were having a good time playing 'Heroin,' smiling. I don't know what that means." Did it sound good? I asked. "Oh, it sounded good," she said. "So good."

That is a great truth about the Velvet Underground that the legend obscures, though it's the basis of the legend: by sounding good, songs like "Heroin" give pleasure. Is it free, the way heroin, the real thing, gives a pleasure that isn't free? For people like Pere Ubu's Peter Laughner, who drank himself to death in pursuit of the sound of "Heroin," obviously it wasn't free. For other people, obviously it is, and why not? "I'd just spent the afternoon with my mother," said a film producer from Edinburgh. "She doesn't recognize me anymore. When I got out of the place I felt I was barely alive myself. Then I passed a newsagent's and I saw the Velvet Underground on the cover of Vox. It said they were playing in Edinburgh that night. I got a ticket, I went. I never thought I would get to see them. They were full of life, but it was so ordinary, too—I don't know. When it was over I walked out of the hall and I felt as if I could start my whole life over if I wanted to."

Originally published in Interview Magazine, September 1993

I had a similar reaction upon first hearing Heroin, at age 16, shortly after the album’s release. I was so terrified I was certain the police would shortly come through my bedroom door and haul me off to reform school. Venus In Furs elicited another reaction: nervous laughter. Black Angel’s Death Song, was the track that locked me in, as it matched up with my willful adolescent weirdness. I hated Nico.

For a kid from the suburbs, or rural fringe, moving into the city in the 1970s or 1980s, maybe still, the Velvets were a talismanic transitional object, a direct hit of the demimonde telling you that you have arrived, you are now a city dweller, the city like something living and dying at the same time, the beauty and ugliness all mixed up, and you now an anonymous denizen of its streets and neighborhoods, and you like it.