The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Red, White, and Blues

February 2003

It didn't start with the terrorist attacks of 2001. People think of freedom and music together for the same reason we think of freedom and water: movement. Music carries a sense of freedom. But music about freedom is a different story. It's like asking for music about movement—a closed circle. Freedom: Songs from the Heart of America (Columbia/Legacy) creates a setting in which the circle opens. Formally, the three-CD set is a pre-certified white elephant: a companion to the 16-part, eight-hour PBS series Freedom: A History of US, which premiered this January and runs through mid-March. (A related exhibition was also on view at the New-York Historical Society in New York City through the end of January.) But the music trips you up straight out of the box.

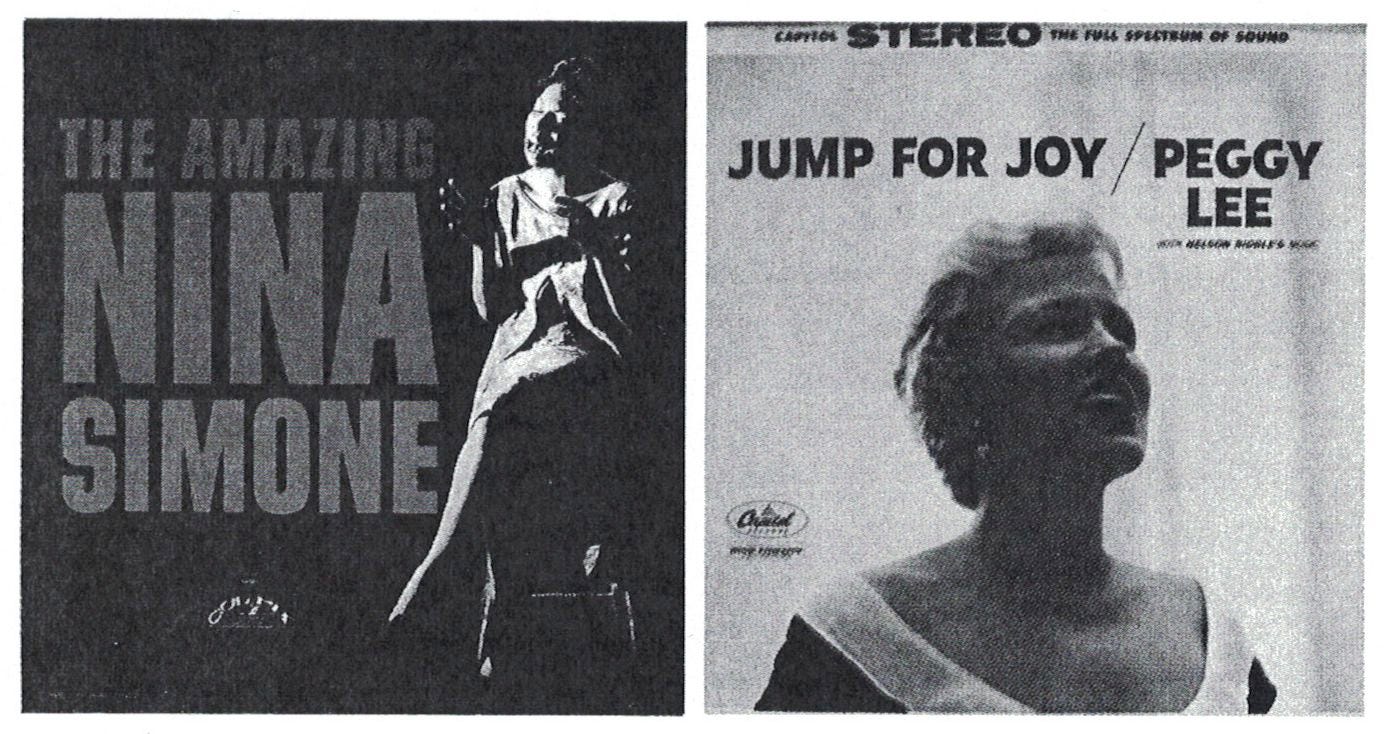

It begins with Nina Simone's graceful, subtle 1967 "I Wish I Knew How It Feels to Be Free." She drifts—less toward freedom than away from it. Suddenly freedom becomes indistinct, unclear: easy to call for, much harder to enact, to live out, even to describe, never mind define. Across Freedom, pious readings of patriotic homilies ("Because All Men Are Brothers" by Peter, Paul & Mary with Dave Brubeck, Richie Havens's "Freedom," the Freedom Singers' "This Little Light of Mine") alternate with numbers in which—whatever freedom is or isn't—the people making the music sure sound free. And you feel free listening to the Broadway Quartet fooling around with "Yankee Doodle" in 1917, to Mahalia Jackson's 1958 live version of "I'm on My Way," and to Duke Ellington and His Orchestra's fabulous live version of "The Star Spangled Banner" from 1956. It's extremely cool, circusy, highlighted by very corny, or very ironic, cymbal smashes—until a clarinet comes in, and you smile, realizing that in this instant the players have looked the country in the face and made it their own.

The country is the subject. Freedom is not about the idea of freedom. It's about freedom—an idea, an adventure, a way of life, a betrayal, a promise, a falsehood—as it has played itself out in the United States, and nowhere else. And that changes everything. Music may be associated with freedom because it suggests movement—but more than that, music dramatizes emotion. Put music and the tale of freedom in the United States together and you get emotion that is not convincing—songs of triumph and celebration, of freedom achieved, won, defended—and there are plenty of those here. Or you get songs in the vein of Nina Simone's—and then the emotion is often all too convincing. The greatest performances here are about what it means not to be free when, the performers are certain, one should be—a notion, the great critic Albert Murray argues, that in another country, without the Declaration of Independence and its like, would not even come up. That's why Bing Crosby's 1932 "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" ("Say, buddy," Crosby's smooth bum whispers from an alley, like the bad conscience of the whole country, its whole story) celebrates freedom as an absence with more beauty and power than Freedom's 1967 recording of the John Philip Sousa march "Stars and Stripes Forever" or the 1941 "Union Maid" by the Almanac Singers could ever do as a presence.

And that is why Freedom comes most completely to life with Louis Armstrong's 1929 “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue?"—why the set perhaps gives the performance a life that, today, without being surrounded by Freedom's dross, lies, and wishes, it could never achieve.

This is the recording the unnamed narrator in Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man listens to over and over again: "At first I was afraid; this familiar music had demanded action, the kind of which I was incapable... I sat on the chair's edge in a soaking sweat." The piece starts very slowly; there's a New Orleans cadence, a cornet solo, then a step back. Armstrong comes in singing, very low. The caricature of his postwar face and voice vanishes. This is an unmade man, anonymous, stepping out of the same alley Bing Crosby will hide in. It's the only real blues on Freedom: "They laugh at you," the man in the song sings, and he wants to know, Why? The words fade into each other, one terrible slur. The man disappears.

On Freedom, freedom is what it is that makes you think you have any right to expect life to be any different.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, February 2003