The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: 25-year-old prodigies—and a prophet who never made it to 25

October 1994

For this 25th anniversary of Interview magazine everything in it had to be themed to that magic number. It was fun to write this pretzel column.

Twenty-five? A nationwide survey concerning the significance of the number in postwar pop music produced bare results. Dave Marsh of New York, author most recently of Louie Louie, came up with Edwin Starr’s “Twenty-five Miles,” Zager & Evans’s best-forgotten “In the Year 2525,” plus, with real verve, the Rolling Stones’ 1964 EP Five by Five—a title recently recycled by the Japanese pop trio Pizzicato Five. After realizing that the Four Preps’ “25 Miles (Santa Catalina)” was really “26 Miles,” and that Gene Pitney’s “Twenty-five Hours from Tulsa” was really “Twenty-four Hours”—and refusing to even consider Chicago’s “25 or 6 to 4” or Y & T’s “25 Hours a Day” on the grounds of gross blandness—I was thrilled by the discovery of Adam Block, San Francisco freelance journalist, that on May 24, 1966, in Paris, Bob Dylan, on the occasion of his twenty-fifth birthday, appeared onstage at the Olympia with a huge American flag draped as a backdrop. Coming at the height of the Vietnam War, this did not go over well, and prompted even the conservative Le Figaro to proclaim LA CHUTE D’UNE IDOLE. On the other hand, it was just that kind of nerve that allowed Bob Dylan to become what Bobby Darin once named his true career goal: “I want to be a legend by the time I’m twenty-five.”

Twenty-five can be a queer year. It’s supposed to be a turning point, but for a lot of people, life isn’t turning at all, just circling, everything on hold. The feeling that your life has yet to even begin overwhelms everything else. For others, though they don’t know it at twenty-five, Nik Cohn’s terrible question to Phil Spector may be all there is: “When you’ve made your million, when you’ve cut your monsters, when your peak has just been passed, what happens next? What about the next fifty years before you die?” Those words appeared in 1969, when Spector was twenty-eight, and three years cold; they apply as well or better to Orson Welles, twenty-five when he made Citizen Kane and set the standard against which all American movies, his own more than anyone else’s, would be judged.

They apply to Bob Dylan, who not only became a legend by twenty-five, but found himself trapped in the legend he became. In a single year, beginning in May 1965, he released Bringing It All Back Home, shocked the Newport Folk Festival with an electric band, released Highway 61 Revisited, left wonderment and confusion in his wake as he toured the world with raging performances that have never been matched, and put Blonde on Blonde in the can, an explosion of artistic risk-taking and achievement that matches any in the annals of American art, and the shadow in which he has worked ever since—his own shadow.

All of which brings home the keenest, most cutting, most memorable appearance of the number twenty-five in modern pop music: in the first lines of David Bowie’s “All the Young Dudes,” as recorded in 1972 by Mott the Hoople. There it is, the life that has yet to begin and the life that’s already over, in one. A hazy, vaguely drunken, vaguely hungover smear of a melancholy fanfare, then Ian Hunter’s voice cutting in, so coldly: “Well, we rapped all night about the suicide / How he kicked it in the head when he was twenty-five / Speed jive, don’t want to stay alive when you’re / Twenty-five.” The song turns into a celebration of youth, all the young dudes carry the news, et cetera, but what about all those the song leaves behind? What about those whose future it cut off in advance?

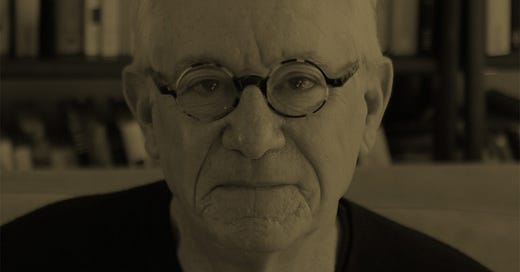

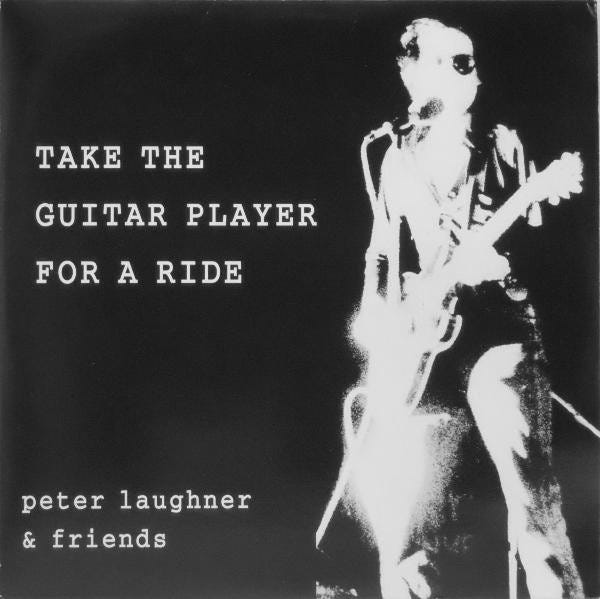

Peter Laughner was a central, mercurial figure in the prepunk milieu in Cleveland in the early and mid-’70s. He was a singer, writer, and guitarist, a founder of Pere Ubu, in his own way a prophet. He would have known “All the Young Dudes”—would have sung it to himself, would have known it in his bones, might have even had to listen, on some bad nights, when too much dope fought against too much alcohol, to his bones singing the song to him—and Peter Laughner never even made it to twenty-five. He died at twenty-four, in 1977, of acute pancreatitis, or, to put it another way, of the romance of self-destruction. At best, Laughner was a local legend, and after not too long, some people would have to try to remember. He was a legendary fuckup, a paranoid with a gun he’d fire, by the end a denizen of nowhere: “Ain’t It fun,” he sang in 1975, in the song of the same name, covered not long ago by Guns ‘n Roses, by way of the Dead Boys, “When your friends despise / What you’ve become / When you know you’re gonna die young.” And yet, listening now to Take the Guitar Player for a Ride, a recent collection of Laughner’s fugitive recordings, it’s hard not to be struck by how much he accomplished, not how little; to be moved by how far he went, not by the way he caught himself up short. Some of the music here—“Cinderella Backstreet,” “Lullaby,” “Amphetamine,” and “Ain’t It Fun”—is so powerful, you can imagine that were Laughner alive today he might never have matched it.

“Take the guitar player for a ride”—does that mean run a con on him, take him out and kill him, or shoot him up?

The line comes from “Amphetamine,” but none of those notions hold as the song takes shape; rather, a man falling to pieces reaches out like a small child asking for a gift he knows he won’t get. The music on Take the Guitar Player for a Ride can make you smile with its skill and flair, and then turn hard to listen to: regret, shame, defiance, and, most of all, death is in it everywhere. Listening to “Ain’t It Fun,” you might ask, What if he had outlived himself? Would people have said, “Yeah, ‘when you know you’re gonna die young’—what a poseur!”

It’s art, that’s all: artifice with a core of flesh. He comes off the well-written, facile litany of ain’t-it-fun horrors and abasements into a little middle-eight story of an almost meaningless, everyday event that’s even worse, and then suddenly it’s as if the art has fallen away and all the hip things he’s been saying are the floor rising up to hit him in the face. The voice begins to shred, and then it breaks: “Oh God!” he says, and you don’t want to listen anymore. He leaves off singing and pounds his guitar, making noise, escaping this moment when, it seems, art has failed. But then he gets it back: Out of that noise floats a solo as elegant as it is cruel, a work of art within this song, this small chaotic incident, where you can’t tell art from life, and age means nothing at all.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, October 1994

When I was 25 and the editor of Creem, Lester Bangs and Peter Laughner talked on the phone often. Sometimes when Lester would get off the phone, he’d look a little pale. I think Laughner’s drink and drug excesses even scared Lester.

Laughner is still considered a legendary figure in Cleveland, along with the also-died-young-and-irascible poet d.a. levy. There are several people still alive who knew both personally. I think there's a quiet consensus that neither man would've endured through the 1980s here; they were men of their very particular times, and those times fell to pieces fairly quickly after 1978. Nonetheless, their ghosts very much still wander through certain bohemian circles and districts of Cleveland.