The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: MTV

November 1993

Some islands of music-video art in the big, wide sea of MTV

The MTV Video Music Awards show this September was draining; it's exhausting to watch so many people trying so hard to be cool. The nominated videos didn't rise above the level of songs that go up for Grammys. It was the usual parade of performance preening, mugging, pose-striking. There's more to videomaking than presenting oneself as an object to be admired—but whether it was Peter Gabriel morphing or En Vogue strutting, this show suggested that the mirror most people want to gaze into is the pool of Narcissus. When is Steven Tyler going to fall in?

Still, without narcissism much of the best of music video wouldn't exist. Sinead O'Connor isn't exactly self-effacing in "Nothing Compares 2 U"; aside from a few moody cutaways it's just O'Connor from chin to crown, lip-synching. It's also riveting: the single work, Michael Stipe of R.E.M. said at the Telluride Film Festival on September 4, two days after he'd performed on the MTV video awards show, that convinced him that mouthing to a tune in a video was more than prostitution or a waste of time.

Along with independent filmmaker Stan Brakhage, Stipe and I were presenting a set of heavy-rotation videos against a background of Bruce Conner movies. Conner, who lives in San Francisco, is a visionary, punning artist who has worked in all sorts of media since the '50s; in the '60s he made a series of music-based short films that all but invented the language music video has plundered ever since. Given that Telluride was a gathering of cineastes, one might have assumed they'd know Conner's Cosmic Ray, a 1961 barrage of fast-cutting and superimposition that disorganizes Ray Charles's ecstatic Newport Jazz Festival performance of "What'd I Say." Probably they weren't going to know the likes of the hilarious video for Billy Idol's "Cradle of Love." Or would it be the other way around?

As it happened, people seemed surprised by almost everything. Audiences laughed all the way through Conner's 1969 Permian Strata, which is nothing more than four minutes of notably weird found silent footage from a Bible movie run against Bob Dylan's "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35." They were turned around by comedian Paul Beatty's "Why That Abbott & Costello Vaudeville Mess Never Worked with Black People," from MTV's "Fightin' Wordz": "'Who's on first?' I dunno. Yo' mama." Hissing and applause were equally hesitant after Martini Ranch's "Reach," directed by James Cameron, of Terminator fame, and included as an example of enormous amounts of money chasing terrible music and cretinous ideas ("It has a real cult following in Paris," filmmaker Robert Kramer said).

The response to Don Henley's "The End of the Innocence" (1989, David Fincher) and R.E.M.'s "Nightswimming" (making its U.S. premiere at Telluride, directed by Jem Cohen) was the most striking. It was quiet, discomfited. These videos weren't simply visually arresting. They were moving.

The video for "The End of the Innocence" revolves around the song's line "that same small town in each of us"—pretty much what Alexis de Tocqueville found in the United States in 1831, and certainly what Robert Frank offered in 1958, with his great book of photographs, The Americans. The "Innocence" clip is so reminiscent of The Americans—which juxtaposed patriotic ceremonies and people standing in disconsolation next to jukeboxes—that Frank cried plagiarism. He received an acknowledgment of his claim; Henley refused to let the video be shown at Telluride without Frank's permission.

Although some of Frank's images are re-created in "The End of the Innocence," that's not all that's going on. Like Frank, Henley and Fincher are looking for "that same small town in each of us" as a field of utopia and betrayal. Like Frank, Henley and Fincher see politics in private moments, resignation in fatigue. Because they're using moving pictures, not still photographs, they can expand the gestures they catch, or stage. An arthritic woman lifting a cup to her lips is so contextualized by fraying Reagan campaign posters and Oliver North on a TV in a poor kitchen, she seems to be acting out the death of the republic. As with Bruce Conner and so many videomakers who came later, Frank invented a language or found it; Henley and Fincher speak it. Frank was new in the U.S.—from Switzerland, a European, distanced and ironic. Henley and Fincher, on their own ground, are bitter and scared.

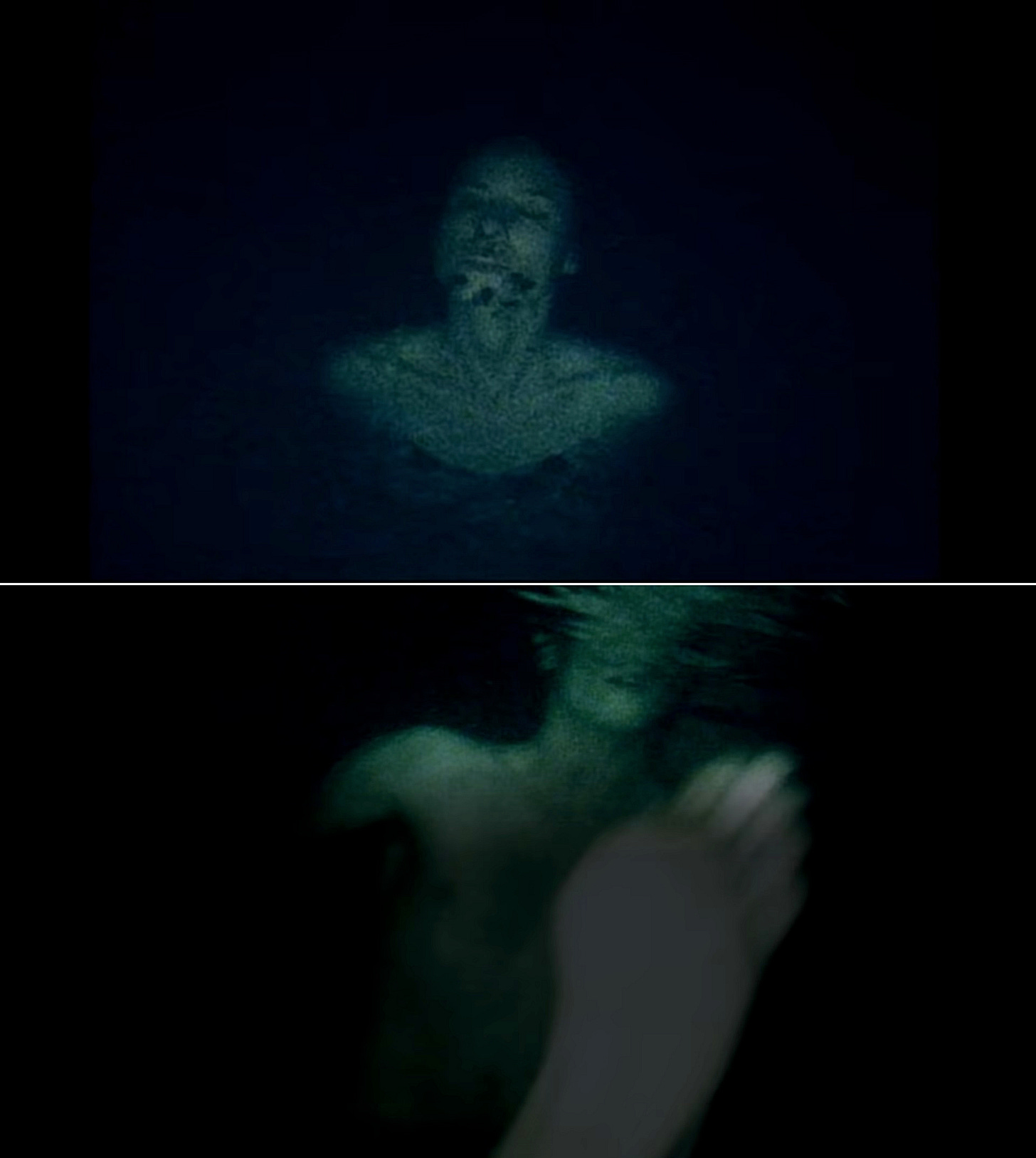

R.E.M.'s "Nightswimming" is about that same small town, or rather a somewhat different small town. It's not in each of us but everywhere around all of us—the viewer has no individuality in this small town. You don't recognize it; it doesn't recognize you. There's nothing here but a moody, then desperate and exultant song about swimming at night, plus footage of nightswimmers framed by chilling images of generic corporate franchised operations: the motels and restaurants and convenience stores everyone has entered in that same small town, wherever it is.

A businessman checks into a motel. He's tired, but the older woman at the desk is a lot more tired than he is; the way she tries to stop herself from yawning in his face can be heartbreaking, if you notice it. The man unlocks his room, sees the motel pool, hesitates, decides, then like a kid playing hooky goes down to the pool and takes off his clothes. In the pool he finds other bodies; they move with his.

This video is an argument, maybe profound, maybe sappy: around the edges of a frozen landscape, in the heart of a small town killed and resurrected to make a field for the living dead, people find ways to act out freedom even if they are not exactly free.

You can't ask for much more out of a song or a video than that. But can you even catch that much—this tiny story—when you see it on MTV? Without a rock star's face in it, this video might communicate more than anything else as an ad for swimwear or some motel chain the name of which you can't remember any more than you can remember the last time you used it. Would that take anything away from what you're seeing?

Originally published in Interview Magazine, November 1993

Why do most music videos seem to diminish songs? Make them seem smaller; trivializing their emotions. Even when music videos are funny they seem to be so in defiance of meaning anything else to the listener; literalizing, restricting the imaginary reach of the song. There has to be exceptions to my ignorant generalizations but this has been more or less my experience of music videos since MTV; so much so that I've avoided them. And this puzzles me, particularly, because I've found music in films can leave such an indelible impression; adding so much to the visuals.