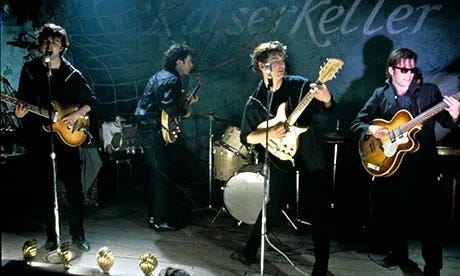

Set in 1960 through 1962, Iain Softley’s Backbeat is a swift little film about the Beatles’ early labors in the Augean stables of brutal Hamburg dives: five-hour sets of jukebox hits offered up to drunken sailors, brawling locals, and strippers on a break or cruising the bar. Onstage, in the movie, the numbers come off the screen with a desperate, sometimes mocking energy. As he did in Christopher Munch’s The Hours and Times (1992), Ian Hart makes a very convincing John Lennon.

Greg Dulli of the Afghan Whigs, Dave Pirner of Soul Asylum, Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, Don Fleming of Gumball, Dave Grohl of Nirvana, and Mike Mills of R.E.M. cut the performance soundtrack that producer Don Was contrived for Softley’s Beatle actors to mime. Unseen, on the Backbeat soundtrack album (Virgin), these modern-day punks do not exactly make convincing Beatles. Their music is full of tiny thrills, surprises, trips, and falls, but it’s from some other movie. You don’t hear the Indra, or the Kaiserkeller, or any other Hamburg joint. You hear some American basement where, as has happened again and again for almost thirty years, hopeful souls have banded together in the light of the myth of Beatle origins to find their own sound.

Like all origin myths, this one had its mysteries: the 1961 Hamburg Beatles were “John-Paul-George,” but also cold-fish drummer Pete Best and hapless bassist and driven painter Stuart Sutcliffe; by the time the Beatles met the world, Best had been replaced by “and-Ringo,” and Sutcliffe was dead of a brain hemorrhage. Someone had died to make this story come true. Told and retold around the campfire of a record player, the myth came alive. In Lester Bangs’s telling: “Hamburg was a crucible, a proving ground, a place where groups were required to play loud and fast and raw all night, hour after hour, using stimulants to maintain the pace, forcing members of the band who had thought they could not sing to take the mike when the leader’s lungs gave out. Things got wild, and the sound took on a mania that became a crucial factor in the coming assault on the United States. It may in fact have been the deciding factor since by any rational—not to mention purist—standard, most of the beat-group reworkings of black American R & B and rock and roll were sloppy, mindlessly frenetic, inept in the extreme; a lot of noise with very little behind it except the enthusiasm of the players. And that, I submit, was what was good about it.”

Dulli, Pirner, Moore, Fleming, Grohl, and Mills might have taken these words as an instruction manual, if not a guide, to the secrets of the universe. Their album makes no claims on a listener by virtue of their fame or skill; it’s not a Beatles tribute record; you can’t even quite connect it back to Softley’s movie. It’s a leap after the inept as if that were the grail—and yet when the grail comes into view, it’s the most ordinary thing in the world. It’s the beer mug on the amplifier, there all the time but you never noticed it.

So you’ve got a bunch of guys who are playing as if they have just now, this night, down in their basement, gotten it right for the first time. That’s the essence of the energy here: we can do it! Grohl plays the simplest drum patterns with flair and excitement; when he tries something even a little bit fancy, he manages to seem just slightly confused. Guitar solos from Moore and Fleming careen out of the songs without sense or direction, and they never get back; the band simply regains the chorus and rams the tunes through to a stop.

What’s most odd, and finally most gratifying, about the music is the anonymity of the whole production—a quality that in a way allows any listener membership in the band. Publicity for the Backbeat soundtrack says that Dulli takes the “Lennon” vocals and Pirner the “Paul” numbers, but Dulli doesn’t sound like John and Pirner doesn’t sound like McCartney. For that matter, Dulli and Pirner don’t particularly sound like the lead singers of the Afghan Whigs or Soul Asylum. They apply themselves doggedly to Barrett Strong’s “Money (That’s What I Want)”; the result is nothing like the absolute attack on decency and honor the Beatles made it in 1963, but a ride on the peaks and valleys of the song’s rhythms for its own sake. The Beatles’ ooo-wooo-wooos on “Please Mr. Postman” were effective components of their rhythm; here the same sounds are only delirious, as if the backing singers have waited all night for the chance to get silly.

As far as I know, this is a completely new approach to the making of a music-movie soundtrack: get some good people together, throw some material at them, and see what happens. Rather than condescending to the material by encouraging or allowing actors to perform it, as with Nashville or The Buddy Holly Story, or freezing it by having actors mime to original recordings, as with Jessica Lange’s lip-synching Patsy Cline in Sweet Dreams, there’s a certain trust in the material, and the myths and legends embodied within it. It’s a trust that if approached in the right spirit, the old songs, the artifacts, will come to life and give back whatever is given to them.

Ronee Blakley was luminous singing her songs in Nashville; stripped of visuals, bare on the soundtrack album, the result was so embarrassing you wanted to bolt from the room. Gary Busey was a reincarnation of Buddy Holly on the screen, moving with clumsy determination, his eyes flashing with intelligence and willfulness; in his soundtrack album you heard not tribute but unintended insult. On the Backbeat album, though, is something different: a sort of imaginary version of a movie that is itself an imaginary version of real events, things that once actually happened. But there’s no once upon a time in this music—no nostalgia, and, in the end, no myth of Beatle origins. It’s just an old story starting up again. “I don’t know how to play that kind of music, that Little Richard music,” Thurston Moore says. “I never did. It’s tricky—a lot of variations on the same chords. I never understood how they could remember all those tiny variations. I listened to a tape of the songs the Beatles were playing then and figured it out. Mike Mills knows that stuff in his bones, but we all played as if we’d just learned it.”

Originally published in Interview Magazine, March 1994

Loved this -- thank you for sharing!

Love that Bangs quote. I've so internalized his take-- ineptitude + enthusiasm-- it's embarrassing. Don't know this soundtrack but reminds me of what some of these same musicians did with Dylan songs for Haynes' I'm Note There. Don't sound anything like the originals but still somehow inspired.