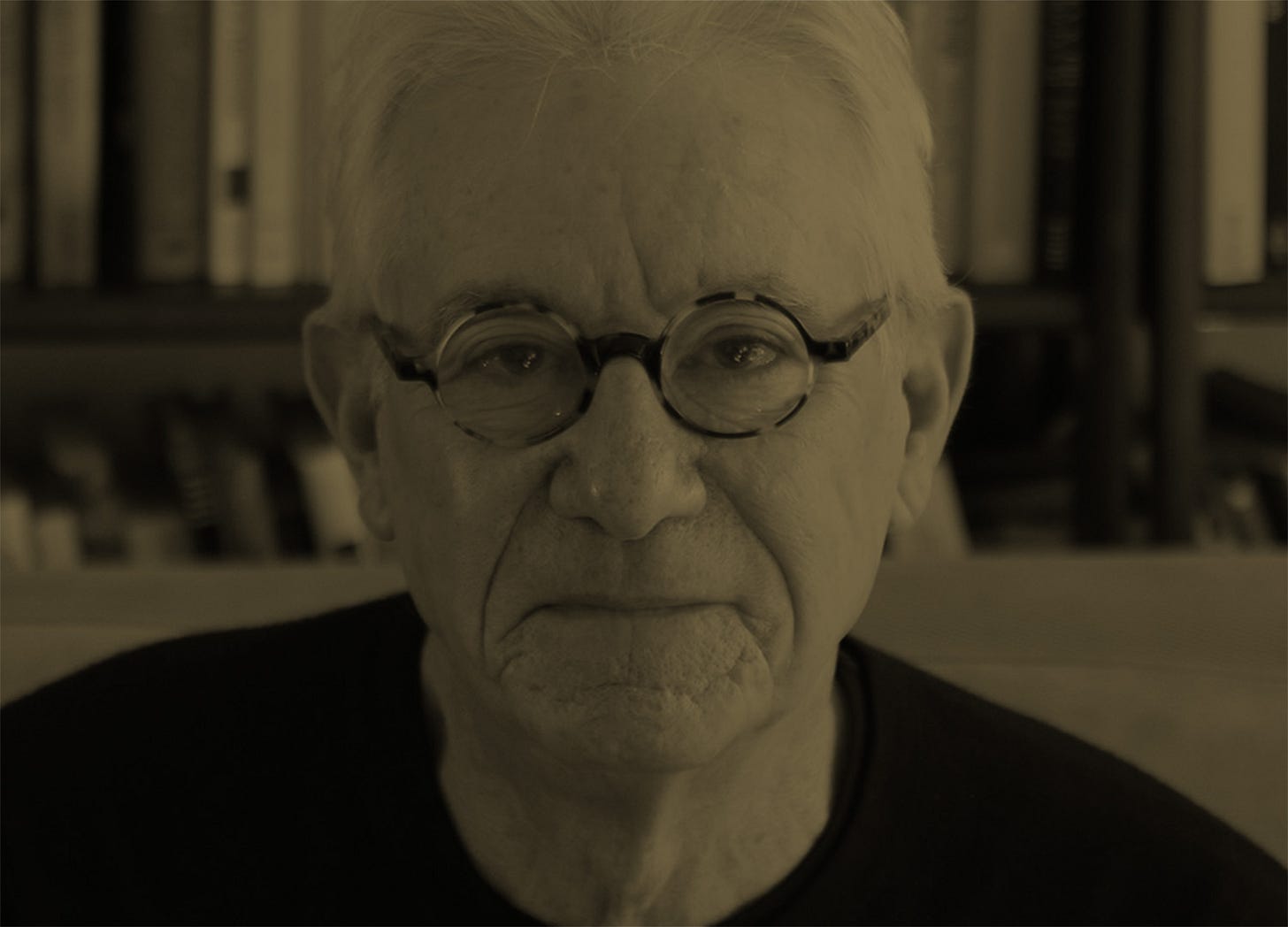

The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: The deepest sound around

June 1997

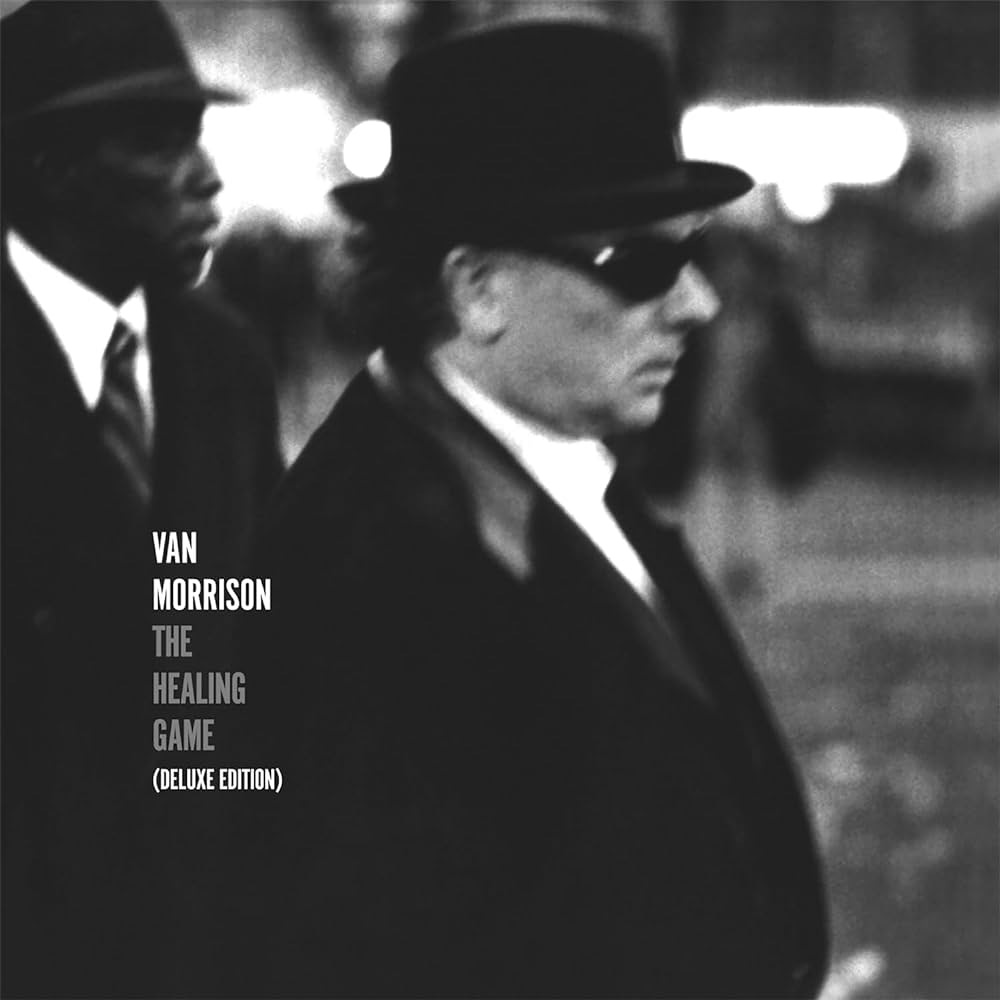

The black-and-white photo on the cover of Van Morrison's recent The Healing Game (Polydor) shows a short, very stocky middle-aged white man on the street, and a

taller black man behind him. Both are well dressed, in dark clothes, with dark hats. The short man, Morrison, is wearing blackout glasses and an expensive white shirt buttoned to the neck; the taller man, flugelhorn player Haji Ahkba, who wears a striped tie, gazes off to the side, as if on the lookout for trouble. It is, you can imagine without trying, a mob boss and his number one lieutenant on their way to settle a score. The expression on Morrison's face, all stone, is impossibly cold.

If this is the mood you carry with you as the music starts, straight off the music tells you you're right: The first lines describe "mud splattered victims... all along the ancient highway," and you sense a vendetta as old as the highway, some internecine tribal conflict that will never be settled. Yet as soon as the scene is set, everything changes, even if the story being told holds to its violence. With the first verse done, Morrison, his voice thick and heavy, glides like an athlete into the chorus, and a tremendous feeling of warmth, of being in the right place at the right time, takes hold. It's glorious: It carries the listener into a musical home so perfect and complete he or she might have forgotten such a thing existed. The deep burr of Morrison's voice buries the words, which cease to matter. "It's when that rough god goes riding," he sings, drawing the words from down in his chest, and you might never know it's the Angel of Death that has you in its embrace.

Almost all the songs on The Healing Game stay on this level. The melodies build on themselves until they communicate like rhythms; the tunes open up like stones you know in your heart but haven't thought of for years. It's soul music, with the reach of Wilson Pickett's “In the Midnight Hour” and the sweep of Aretha Franklin's “Ain't No Way,” but without glamour, or really even a hint of performance, of gestures extended or notes held for effect. The street this music moves down never disappears.

Van Morrison has been making records since 1964, when he came out of the Belfast blues and R&B scene with his band Them. The Healing Game, which, with the title song and another track, "Waiting Game," calls up the film The Crying Game, that whole drama of Irish resistance and regret, is his best album in twenty years. Go back to the 1979 Into the Music, a buoyant, serious, blazingly ambitious testament—against The Healing Game it sounds thin, poppy, ephemeral, although it isn't remotely so when it's allowed to claim its own air. Morrison's records of the last decade fade into irrelevance against his new music; they don't even make sense.

The Healing Game makes me think of the original Fleetwood Mac, led by Peter Green in the late '60s. As a blues guitarist, Green, who had earlier replaced Eric Clapton in John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, had by 1970 been and gone from places—continents in the heart—Clapton would never get to. He played an occult blues, a fantasy blues, in which everything was slowed down and emotions appeared only to decay. As a singer, he sang in his own voice. There was never any doubt that he was white and English. The terrible remorse in his voice, you could think, wasn't for the love he'd lost or the life that failed him. It was a sorrow over his conviction that, as a white Englishman, the blues would always be out of his reach. It was that remorse, though, that made his blues completely real.

Morrison came from a similar place, and over the past few years he has seemed to fall back before his masters, to perform merely as a product of his influences. All of that is left behind now, even if, as a singer of confidence and pride, he sometimes goes almost as far as Green once did.

Morrison dominates each song on The Healing Game—but the word song seems much too small here. Like the rough god he sings about, Morrison is astride each incident in the music, each pause in a greater story, but often the most startling moments are in the margins. It might be Pee Wee Ellis's twisting sax-playing, or the backing vocals of Katie Kissoon, or the side-singing of Georgie Fame, but all of them bring a certain realism to the setting. Morrison is the philosopher, the man of knowledge and experience; the others are the street he walks on. Ellis's work is too individualistic to rest as mere accompaniment; he can make you forget you're listening to a self-evident, self-presenting master. Kissoon and Fame are slight singers, ordinary in every respect; they sing and talk like passersby, making room in the story for the listener. Thus, in the furious "Burning Ground," which is about getting rid of a body, it's clear who'll be doing the dirty work. Sounding as gleeful as the Kray twins, Morrison simply orchestrates the action and gets the kicks. The listener gets to watch.

"I'm not gonna fake it like Johnnie Ray," Morrison declaims in "Sometimes We Cry." Its a cruel dismissal of a once-groundbreaking artist who died miserable and forgotten. But there is such strength in Morrison's singing, it can make you wonder what the cruelty is about.

It was in the early '50s that Ray set the stage for the rock 'n' roll singers, black and white, who would follow him with an emotionalism that was shocking in its nakedness. Singing a tortured pop version of rhythm and blues, Ray would cry onstage, and even if it began as an act, the tears coming every night like Pete Townshend smashing his guitar, soon enough the desperation Ray sparked in his audience blew back on him, and some nights, right there, he would break down. Then his moment passed; his career collapsed with arrests in men's rooms and attempts to go straight, both musically and as a public figure. So how did Johnnie Ray fake it? What was it that he held back? Was it that, exposed to everyone for who he really was, he threw his music away and tried to pretend he was just like everybody else?

Van Morrison has always made much of the fact that he's not like everybody else, that there's not a word he's said he'd ever take back, that he's tough and true. Sometimes he sounds like a braggart drunk in a bar, but not this time.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, June 1997

Hank Williams Sr. was an admirer of Johnny Ray in the early 50's appreciating the emotion and honesty the crooner brought to his songs. In Martin Scorsese's The Irishman, one of Ray's songs provides background to a mob hit, so both Marty and Robbie Robertson remained fans. Too bad Van Morrison (and Eric Clapton) have become such obnoxious cranks on public health issues. Unless one really compartmentalizes their art and careers, the wacky and loud anti-vax opinions they hold kind of sully their latter day legacies.

Even on record from beyond the grave, Johnnie Ray brings those feelings out in his listeners. The very much still alive Van Morrison often does as well.