The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: The times they are a-changin' again

March 1995

I admit I was thrown by the Bob Dylan segment of the NBC News end-of-the-year wrap-up on December 30. After the requisite Bobbitts-Simpson-Tonya-Michael Jackson montage, and a similar smear of Rwanda-Bosnia-Haiti-Chechnya, there was bright footage of Newt Gingrich and other Republican stalwarts celebrating their November triumph—with Dylan's 1964 recording of "The Times They Are A-Changin'" ("Come senators, congressmen / Please heed the call / Don't stand in the doorway / Don't block up the hall") churning in the background. Despite Gingrich's immediate postelection identification of the seemingly long-gone counterculture as the enemy within, the song sounded so weirdly apt it was as if the Republicans had now seized all rights to it, along with the rest of the country. The NBC orchestration conflated all too perfectly with the new TV commercial Taco Bell began running about the same time, announcing a burrito-plus-CD promotion (you can pick up a sampler with General Public, Cracker, the Spin Doctors: "Some call it 'alternative' or 'new rock'—we just call it 'dinner music'") with footage of dancing young people turning Taco Bells into dance clubs. "Don't let it pass you by," said the announcer in a friendly voice, which suddenly, unexpectedly, turned hard: "Because there is... no alternative."

On the other hand, it didn't bother me at all that Dylan recently licensed "The Times They Are A-Changin’”—certainly his most famous, catchphrase-ready protest song, in the mid-'60s an inescapable affirmation of the power of the civil rights movement to redeem the nation's soul—to be used in a TV commercial for the Coopers & Lybrand accounting firm. I think all songs should go up on this block. As with the NBC joke (perhaps inspired by Tim Robbins's Bob Roberts, in which the right-wing folksinger-politician storms the heights with "The Times They Are A-Changin' Back"), it's a way of finding out if songs that carry people with them, songs that seem tied to a particular time and place, can survive a radical recontextualization, or if that recontextualization dissolves them.

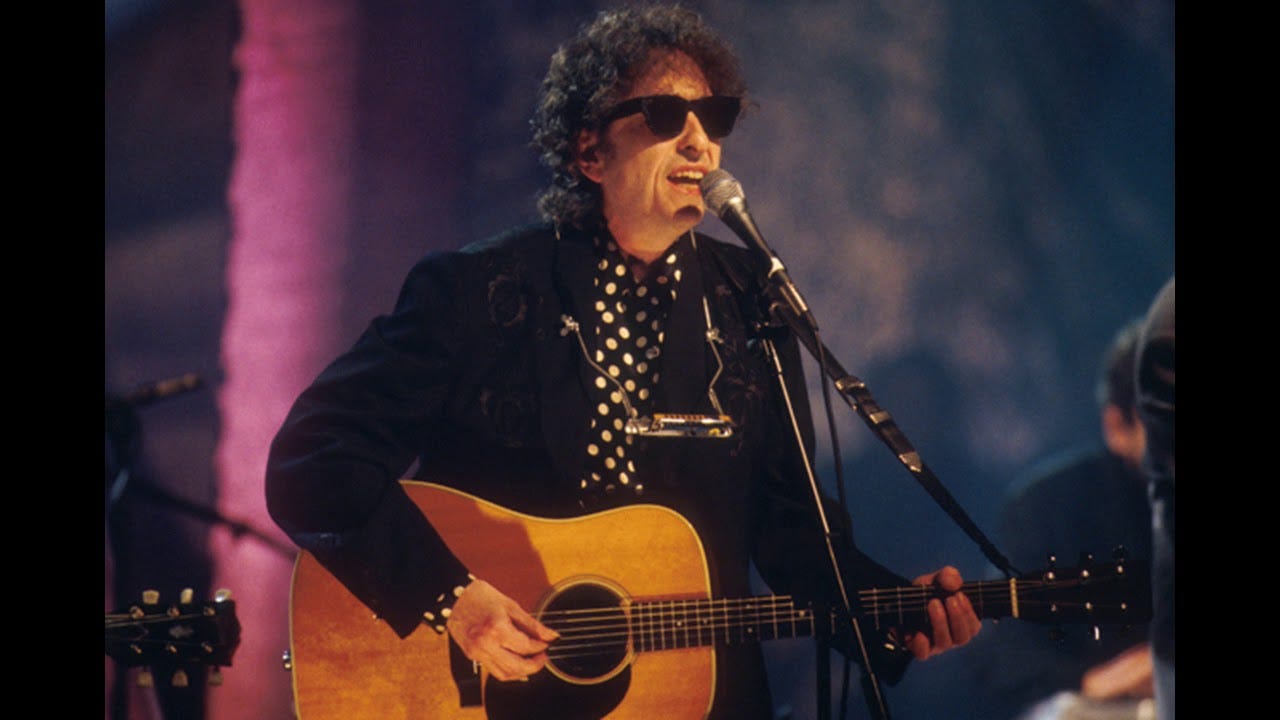

The Beatles' "Revolution" may never recover from its Nike commercial, but Coopers & Lybrand didn't lay a glove on "The Times They Are A-Changin'." When Bob Dylan sang it on his MTV Unplugged show—taped November 17 and 18, little more than a week after the election, it aired December 14 and should be out as an album by now—the song was full of new life. With a lively band around him, Dylan took the lead on acoustic guitar, making more of the song's inner melodies, its hidden rhythms, than ever before. He slowed the song down, as if to give it a chance, as it played, to catch up with the history that should have superseded it. Or was the feeling that the song was still lying in wait, readying its ambush? As he did throughout the performance, Dylan focused certain lines, words, syllables, looking around behind impenetrable, blacker-than-black dark glasses, as if to ask, "Are you listening, are you hearing, who are you, why are you here?" By design, the people in the front rows of the audience were young enough to go from this show to the taping of the Taco Bell commercial without skipping a beat, but breaking such a rhythm seemed to be what Dylan was doing this night with "The Times They Are A-Changin'."

Emphasis was the motor of the performance, with quietly stinging notes highlighting especially "If your time to you is worth savin'," a phrase that in 1964 felt certain and today can feel desperate and bereft—a deeper challenge. Or perhaps those words, sung and played as they were, were now a challenge for the first time. If Dylan was celebrating anything as he retrieved the number, it was menace. The song took on a new face, and you could hear it as if it were putting a new face on a new time. Instead of Great Day Coming, the feeling was, Look Out. What opened out of the song was not the future, but a void. It was all done lightly, with a delight in music for its own sake: Dylan's gestures and expressions, like his black-and-white polka-dot shirt, radiated pleasure. You didn't have to hear anything I heard, but what you couldn't hear, I think, was an old warhorse of a greatest hit trotted out to meet the expectations of the crowd.

"The Times They Are A-Changin'" was not in any way the highlight of the show; that was probably "With God on Our Side." With its circa 1952 grade-school-textbook summary of American wars—the Indian wars, the Civil War, the forgotten Spanish-American War, the First World War, the Second World War—it brought the same displacement the Cranberries play with in "Zombie." There, the word 1916 leaps out, because today the mention of an event that took place before the song's intended audience was born is a bizarre use of pop language. It's a strange violation of an art form that sells narcissism more effectively than anything else.

Seven years ago, describing Bob Dylan at the great Live Aid concert in 1985, Jim Miller, in perhaps the best short overview of Dylan's career, spoke of a "waxen effigy," a "lifeless pop icon," "a mummy." The guy onstage in 1994 was more like a detective, investigating his own songs—and then treating them as clues, following them wherever they led, to the real mystery, the real crime. For the last year or so, the most ubiquitous appearance of this pop icon in pop media has been that moment in Counting Crows' "Mr. Jones" when Adam Duritz shouts, "I want to be Bob Dylan!"—and it's a wonderful non sequitur. What in the world does that mean? As it seemingly was not a few years ago, what it means to be Bob Dylan is now an open question; as Taco Bell insists, there may be fewer open questions around these days than one might have thought.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, March 1995

I'm not so sure all songs should go up on the commercial block. I remember playing Sly and the Family Stone to a friend unfamiliar with the group. Upon hearing "Everyday People" he laughed and said "Is that the song from the Toyota commercials?" Ever since then I've felt there was something tawdry about first experiencing a great song through a dumb commercial.

"it's a way of finding out if songs that carry people with them, songs that seem tied to a particular time and place, can survive a radical recontextualization, or if that recontextualization dissolves them."