The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: That Old Mekon Magic

April 2000

The Mekons have been a fly in the pop ointment for so long that you can bump into them again at almost any time without feeling like strangers. They began in Leeds, England, in 1977, as a crowd of impish left-wing punk ranters. They made their strongest music in the mid '80s, when Margaret Thatcher appeared to them as Medusa, her face capable of turning all they loved into stone.

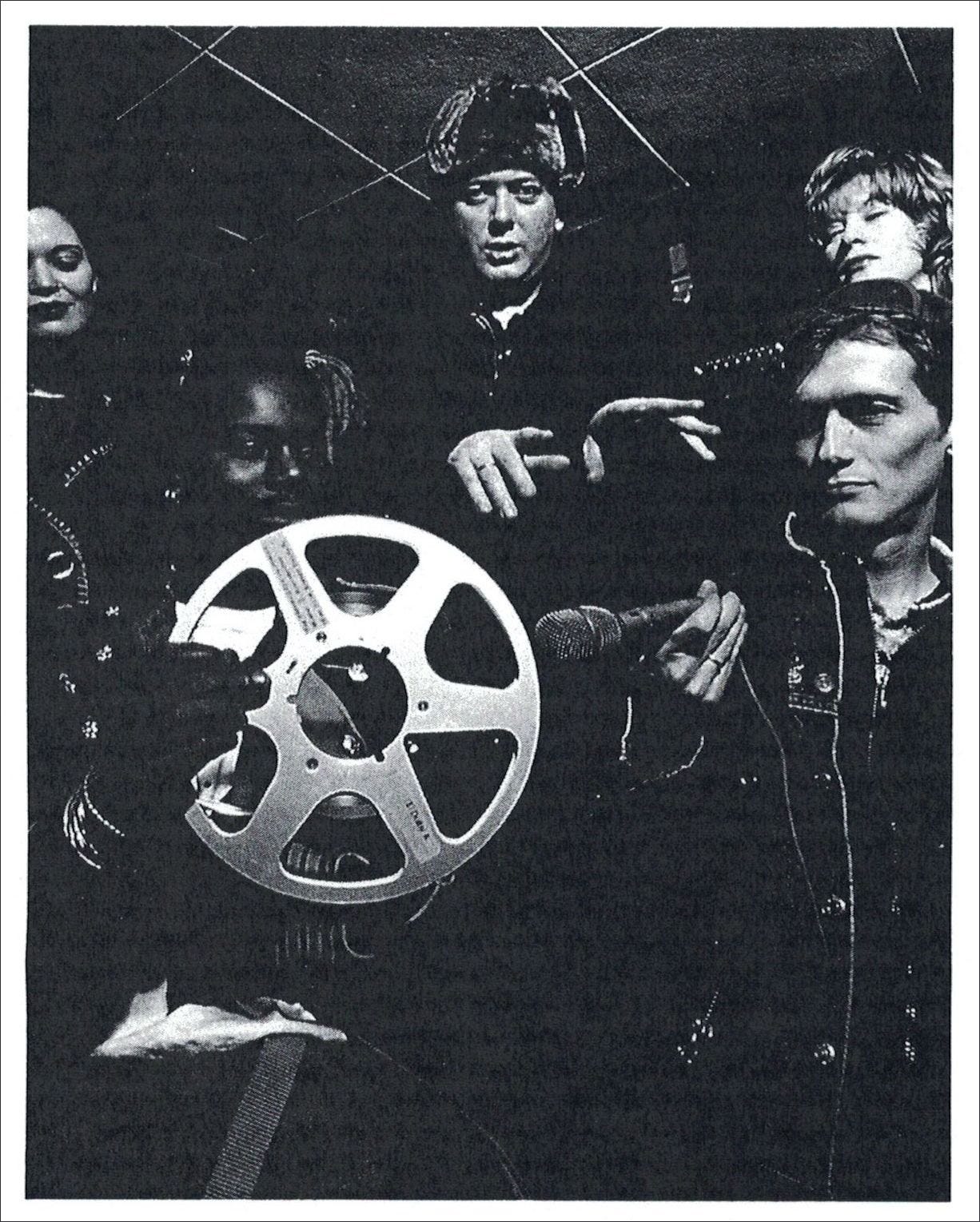

Today they come together from their homes in Chicago, Leeds, San Francisco, and elsewhere as an assemblage of friends bound by primitive music and a shared past, and a certain sense that the band may outlive whoever's been part of it. Only writers Tom Greenhalgh and Jon Langford remain from the first days, but the history they carry with them is now part of singer Sally Timms' story, too—just as it's hard to imagine the band once existed without her.

So if, in the past couple of years, you missed Timms' increasingly deep and playful solo albums, or Langford and drummer Steve Goulding's work with honky-tonk band the Waco Brothers, you could be confident that the Mekons were still out there, somewhere. Even if you passed by the last few Mekons albums, from their collaboration with the late Kathy Acker to 1998's Me to two collections of odds and ends, you could figure that sooner or later you'd find you were stuck in the same train station with no one else to talk to, and the conversation would begin—again, or for the first time, or even the last time.

That's the feeling all over Journey to the End of the Night (Quarterstick): a cloud cover of melancholy and curiosity, a belief that there is nothing new under the sun combined with the notion that with one more sunrise there might be. "The wish comes true," Timms says calmly in "The Flood," her voice then rising, warbling, at once trembling and grinning: "But not through wishing." As a mere set of words, the song describes nothing but a mystery-story encounter between two strangers, then a quick fuck in a field or a parking garage, but the orchestration of the mere words makes their story into a whole world, a memory around which a life will turn forever.

A synthesizer raises a chilly, rainy, Shoot the Piano Player backdrop for small-time crime and self-conscious dread; a guitar scratches in the background, as if knocking on a window.

Timms drifts through the song like a character in someone else's dream, distant, not quite in focus, a beckoning hand that turns to air as soon as you grasp it. And yet, as always, she is someone whose voice lets you imagine a person behind it: someone who'll never be able to tell half of what she knows, simply because no one lives forever, and that's how long it would take. So instead of a look of helplessness or desire on her face, there's a mask of slyness, of conspiracy: What if, by listening to her secrets, they become yours? Now it's just the two of you in that railroad station, and you realize that to listen to this woman may be to join her—but in what? As Langford rolls the tune with a soft, repeating set of blips on a melodica, you're swept away by a romance that's equal parts sex and espionage, and nothing could sound more alluring.

The songs on Journey to the End of the Night are so good, and so different, that any one of them could function as "The Flood" can: as a key to the rest of the music. There is the odd "City of London," a travelogue of unthreatening ruins—until another, much bigger female voice screams "TEN SQUARE MILES OF HATE" as Timms quietly mouths the same words to herself like a rosary. There is the perfectly charming "Neglect," a song of excuses that turns into a recitation of self-hatred. In "Myth" and "Ordinary Night" there are the odd echoes of old English folk dances in jerky rhythms that seem to slow down in ways that make no sense, suggesting gestures that are no longer made, paths in forests that no longer exist, names that no one would answer to. The songs aren't funny, but inside almost every one of them there's the feeling that the singers and players are sharing a joke so good it would be a sin to just tell it and have it over with.

That's "Last Night on Earth": a cheap, bouncy reggae beat for an anguished Jon Langford vocal that stretches right across all the years the band has seen, all the members it has left behind, all the villains it has cursed, to the faith that, finally, there are some things only a fiddle can say. Susie Honeyman saws away, and the result is a simple, radiant theme that can stay in your head for days. She calls a dance, she plucks her strings, and time doesn't end, it swirls. The dozens and dozens of people who have for more than two decades passed through the Mekons appear in that deserted railroad station, not waiting for a train but hoping none will ever arrive, so they won't have to leave. They join hands in a circle, and move in a queer two-step, the right leg placed behind the left, clumsily, unnaturally, but drawn by something bigger than they are.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, April 2000

Greil, I’ve been reading your work since Mystery Train and know the Mekons are very special to you. Nevertheless I have never knowingly listened to them. (Sorry!) Is “Journey to the End of the Night” a good starting point?