The 'Days Between Stations' columns, Interview magazine 1992-2008: Heavens to Betsy and the Fleetwoods

January 1994

Two groups from different decades prove there’s more to Washington rock than Seattle

For the last year or so, whenever anyone has asked me what I’ve been listening to, I’ve found myself answering, Heavens to Betsy—and then, the Fleetwoods. Shouldn’t the two most interesting groups to come out of Olympia, Washington, have something more in common than that they’re both unique?

Heavens to Betsy are a two-woman band (Corin Tucker: words, guitar, occasional drums; Tracy Sawyer: bass and drums), old friends from Eugene, Oregon, who began making music together in 1991, in the riot grrrl milieu of Olympia’s Evergreen State College. They’ve released a bare eight recordings, scattered across singles and compilation albums on various small Olympia labels, and seven of those eight are as overpowering as they are rough and crude. The songs or the aura that surrounds them, the prickly, squirmy feeling of people digging into themselves in order to get under your skin—communicate like acts of violence.

The Fleetwoods were perhaps the gentlest of all doo-wop combos. They started at Olympia High School in 1958 as the Saturns, a vocal group comprised of Gretchen Christopher and Barbara Ellis, fellow cheerleaders and oldest of friends. (As every bio notes, they were born just days apart in 1940, spending time together in the same Olympia maternity ward.) The addition of classmate Gary Troxel gave them an unusual three-part harmony, with male and female voices sharing both leads and backing parts, lyrics and doo-wahs. The combination made their composition “Come Softly to Me” an almost instant nationwide number-one hit in 1959, after which their record company pushed Troxel to the front and repositioned the women in conventional supporting, musically housekeeping roles. Still, right through to 1963, with “Mr. Blue” (also number one in 1959), “Runaround,” “(He’s) The Great Imposter,” “Confidential,” and “Tragedy,” the Fleetwoods were an uncanny oasis on the radio, a locus of exquisite longing and delicate suspension, a floating sound that, for the two or three minutes each play lasted, made everything around it seem to count for nothing.

Heavens to Betsy don’t have quite the same effect, because they aren’t heard on the radio, but they have the same dissolvent power—dissolvent, a nice, soft word that seems inappropriate for Heavens to Betsy’s harsh attack. So let’s say corrosive, and see if that harsh, punky word can work for the quiet, forgiving Fleetwoods.

With its perfectly mnemonic introduction—Troxel’s high “do doobey do, dum dum, duh-um do dum, do doobey do” (the phrases then running under Christopher and Ellis’s leads until Troxel comes forward, and the two women drift behind him in a wash of oohs and hums)—“Come Softly to Me” remains an incandescent record, and as found as it was invented. Apparently, it first began to take shape after Christopher and Ellis’s Saturns had finished auditioning a string of girl belters for a third voice on their cover of the Five Satins’ “In the Still of the Nite.” No, Christopher told one last too-loud hopeful, she wanted the “Still” in the song—the stillness. When Troxel joined, he grafted on a bit of the Dell-Vikings’ “Come Go with Me,” and that was that.

In Heavens to Betsy’s “Baby’s Gone” (on Throw: The Yoyo Studio Compilation, Yoyo Recordings, P.O. Box 10081, Olympia, WA 98502), Corin Tucker seems to climb a staircase with every line. Big guitar chords shimmer and break like something out of Jimi Hendrix’s version of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” but it’s Tucker’s clipped and certain diction that makes this song its own sort of anthem and also the cruelest, most self-immolating punk rant this side of the Mekons’ “The Building.” For “Baby’s Gone,” the instrumentation is atmosphere, setting. The action is all in the voice.

The house is empty, the singer’s footsteps make an echoing noise as she strains for the landing; each time, at the top of the stairs, there is a nothingness, dead air and dead weight, that stillness, and so every line begins the process all over again. There’s no progression in the music. There is a tremendous reach in Tucker’s voice as she sings, to herself—imagining her parents in front of her—about having sex for the first time, that day, and it’s still shaking her: “I know sex is what I shouldn’t do/I know what I can’t tell you… I’m your little girl forever/I won’t make you ashamed.”

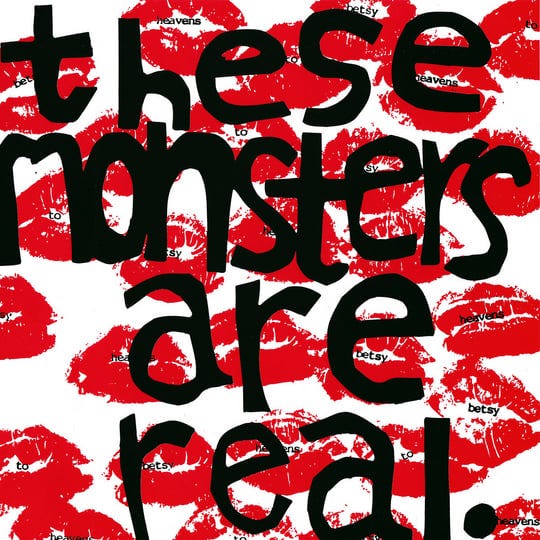

As in “My Red Self,” a primitive, nearly tuneless song about menstruation, with the singer seemingly standing naked in front of her mirror (on Kill Rock Stars, [KRS/Cargo]), or the raging, unstable “My Secret” (on a single shared with Bratmobile), or the four preternaturally intense tunes on the recent EP These Monsters Are Real (KRS, 120 NE State #418, Olympia, WA 98501), the drama that’s taking place sucks up the ordinary, the everyday, the heroic, and the mythic, all at once. “Maybe he loved me/Maybe he didn’t I don’t know”—the way Tucker throws away “I don’t know,” just letting the words and the idea break up, contains many kinds of violence. Another throwaway, “You tell me to calm down, what is your fuckin’ problem”—in “Me and Her,” an almost conventional rhythm carrying the story of a busted girl-girl love affair—is as close to realism as pop music can get, a closeness that carries an aesthetic charge, a shot of pleasure, altogether independent of plot and moral.

Always, whether it’s the campily theatrical ululations in “Monsters” suddenly ambushed by the most horrible and convincing recorded screaming you’ve ever heard, or the soft chorus of “Baby’s gone away” followed by “Sometimes condoms break,” the voice claims the drama—and the essence of the drama is the feeling, in each song, that it’s the last word you’re going to hear from this person, the singer, whoever she is. You don’t know if she’s going to shut up or be shut up, but the possibility waits like the next act at the end of every song: silence.

The Fleetwoods started with silence, and as close as they could return to it without giving in completely was as close as they got to nirvana. For Heavens to Betsy, silence is the last word of a song, and then just a void. Hearing the Fleetwoods now (on Come Softly to Me: The Very Best of the Fleetwoods, a twenty-eight-track CD on EMI), their achievement still seems altogether remarkable. They recorded their own little tunes a cappella, sent them to Hollywood for some instrumental overdubs, and before too long the whole country was listening to them. Heavens to Betsy’s music is just as homemade—but the radio is no longer open to surprises from the sort of nowhere the Fleetwoods and Heavens to Betsy share. So their stories are as different as different can be: with their success, the Fleetwoods bent to the demands of the music business and tried to become like everybody else. Heavens to Betsy deepen their extremism with every new release, as if each public offering only drives them further into exile.

Originally published in Interview Magazine, January 1994

Not to mention they are about as musically, sonically, opposites as you could find in two groups from the same town.

This story was old 30 years ago so how come it still sounds so fresh? It makes me think the music would, too. Timeless, as they say, on all counts - thank you!