Kenneth Anger died May 11 at 96. He had alienated countless of his friends and supporters and even fans who found their way to him as if on pilgrimages. His demands and paranoia and egomania regarding almost everyone he worked with were, sooner or later, inescapable. I know one person who invited Anger to stay with him; after months, he couldn’t get him out of the house, because Anger had filled the place with acolytes and taken it over as his own domain. When I interviewed him for the performance recounted below, it was if the legend he worked all his life to surround himself with was some kind of joke. He was soft-spoken, direct, modest, inquisitive; a complete pussycat.

My favorite of all his movies: Rabbit’s Moon, the 1971 version of a film made in Paris in 1950—for the fabulous doo-wop soundtrack, headed by the Capris’ “There’s a Moon Out Tonight.”

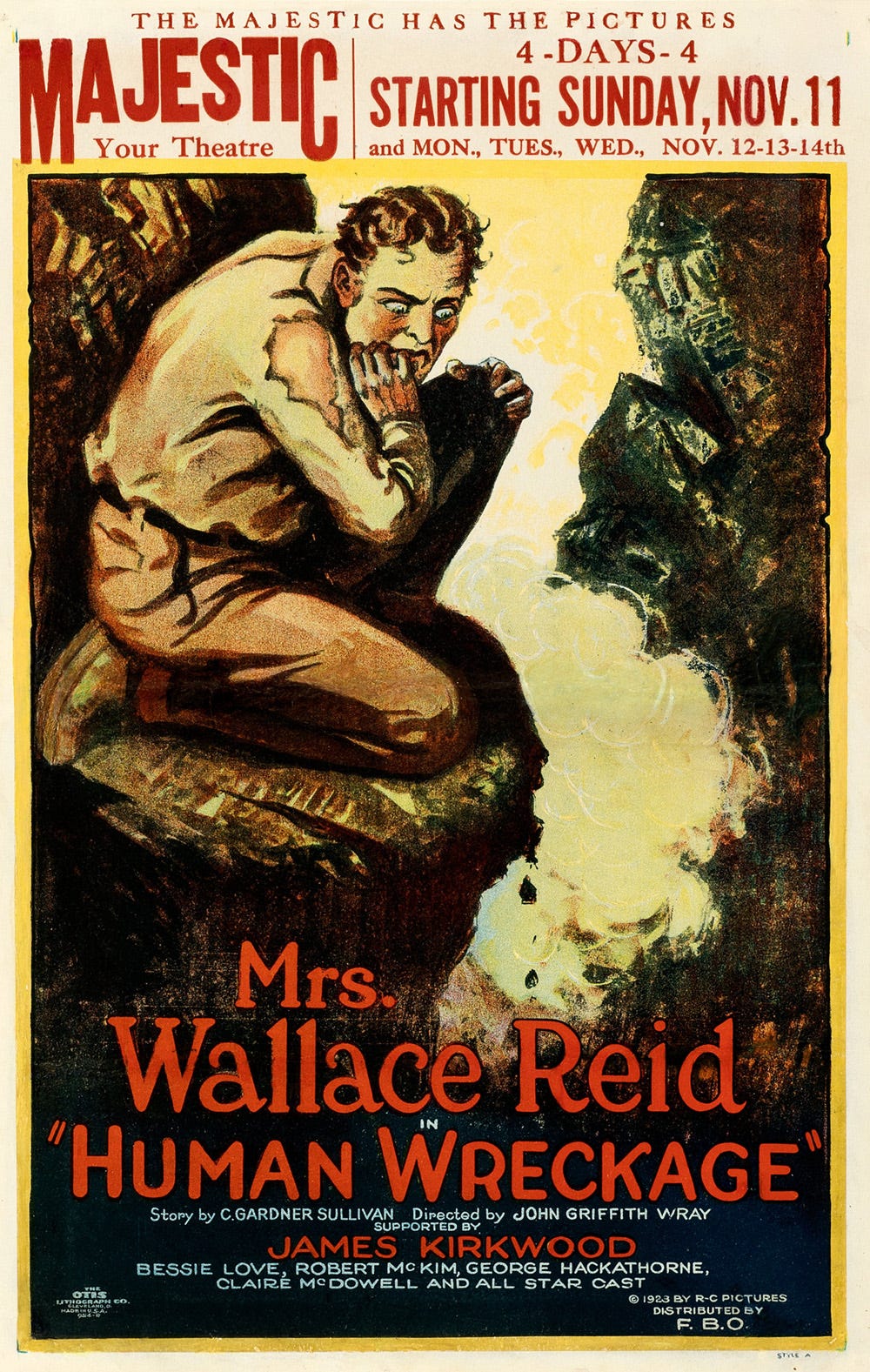

“Films from Hollywood Babylon” is a montage of clips and full-length pictures, featuring the silent stars who expire across the first hundred pages of Kenneth Anger’s recently expanded and republished chronicle of Hollywood scandal. Like the book, the show is halfway between a celebration and a horror story. The images of the performers that obsess Anger—Barbara La Marr, Alma Rubens, Wallace Reid, Olive Thomas—are truly luminous, but the bluenoses and dope habits that did them in fascinate Anger no less. His involvement with these forgotten idols of the teens and ’20s combines a wish to perpetrate, indeed to extend, the mythic status these stars had in their time with the need to turn their myths inside out, to bring the stars back to earth—or below it. Deliberately confusing prurience and puritanism, Anger holds out his own image of Hollywood, which he at once worships and abhors: the Love Queen, answerable to no man, only to the needle; an otherworldly perfection of the flesh slowly rotting away. It would be too simple to say that Anger worships the good and abhors the bad; what he wants is the image whole.

Anger unveiled his new show in Berkeley, September 17, under the auspices of UC’s Pacific Film Archive, run by Anger’s long-time friend Tom Luddy. A crowd of 700 filed into the biggest hall on campus, to be hit with the heaviest load of incense anyone had smelled in years—great pots of it were burning on the stage, which was decorated by icons of Monroe, Garbo, Theda Bara, and Joan Crawford, who was shown clutching two Pepsi bottles. Off to one side an artist was completing a portrait of Valentino in the style of pictures sold on Sundays outside of public parks—he continued to work on it throughout the evening. In the middle of the stage stood a neon sculpture—two enormous bow-lips, lettered “HOLLYWOOD BABYLON.” The sound system played the Doors’ album Strange Days.

Anger appeared, dressed in a tight white suit, skimmer, purple shirt, red tie, and white shoes. Inconspicuously, he knelt before the icons throughout the Kinks’ lovely “Celluloid Heroes,” and as the tune ended he leaped to his feet, threw his arms wide, and raced back and forth across the stage, his face full of light. The projectionist flashed shots of Valentino and James Dean. “The side show,” Anger pronounced, lifting a violin and bow outlined in gleaming white neon. “The side show!” He fell to one knee, and played his way through an inspired pantomime/lip-sync of Blue Magic’s “Let the Side Show Begin,” which had just begun to sound through the hall. I was impressed. It was exciting.

I first saw Anger in 1963, 100 yards from the building in which the Hollywood Babylon show was taking place, at a retrospective of his pictures. Fresh out of the suburbs, I knew nothing about homosexuality, sadomasochism, drugs, depravity, or various other subjects of the films that were shown that night, but I did know something about rock and roll, and when, in the midst of Scorpio Rising, there appeared a shot of Jesus riding an ass while on the soundtrack the Crystals sang “He’s a Rebel,” a certain connection was made. Anger’s performance of “Let the Side Show Begin” proved he still had the best sense of humor in cinema.

The side show completed, Anger rose to business, commencing a monologue on early Hollywood that described the miasma of dope and sex into which the first stars enfolded themselves as soon as they could afford to. He pranced, pirouetted, reaching heights of indignation and simpering contempt, almost convulsed with delight, as if his whole life had pointed toward this night.

First on the screen was The Mystery of the Leaping Fish, a 1916 dope comedy starring Douglas Fairbanks as “Coke Ennyday,” private eye. It was flatly hilarious. Coke Ennyday appeared with a belt strapped across his chest holding a couple of dozed syringes, which he shot minute by minute, occasionally pausing to dip into a huge bowl labeled “COCAINE” with a powder puff or with his bare hands, showering the room with dust. The plot grew out of a surprisingly enlightened, or, at the least, modern distinction between hard and soft drugs. Coke Ennyday, it turned out, earned his keep catching morphine dealers.

Morphine, in fact, underpinned the most interesting offerings of the night (which also included Chaplin’s “Idle Class,” 1921, featuring his child bride Lita Grey, two Fatty Arbuckle comedies, film of Valentino’s funeral, and the like). Coke Ennyday was followed by a clip of Wallace Reid, who did indeed take coke any day, and also, thanks to Paramount Doctor Feelgoods, hop. Then the night’s one full-length feature, The Red Kimono, inflicted upon the American public in 1926 by Reid’s wife. After exposure as an addict, Reid, who had gone from, as Anger described him, “the Robert Redford of his time,” to a wizened half-corpse, was packed off to a Sanatorium, where he died within a year. Mrs. Reid—“THE PROFESSIONAL WIDOW!” Anger screamed—got together with cinema morals czar Will Hays and launched an orgy of filmic terrorism that began with Human Wreckage (1923), a lost dope epic starring Priscilla Bonner as a junkie who, raped, gives birth to a junkie baby. The film apparently reached its low point with the appearance of Mrs. Reid herself—a woman with the least sympathetic screen presence I have ever seen—as a noble social worker who arrives at Bonner’s squalid flat to relieve her of her baby. (All that survives of the film, it seems, is a still of this very scene, showing Mrs. Reid clutching an extremely freaked-out infant as Bonner determinedly shoots up in the background.) The irony of the close resemblance of this episode to one of the most chilling parts of Intolerance was unfortunately lost with the film.

Human Wreckage (and that is a great title), was a big hit, and Mrs. Reid took off across the country in her widow’s weeds to promote it, returning to make The Red Kimono, her prostitution epic, also starring Bonner. “I’m going to show it all!” crowed Anger with mad glee. “All SEVEN reels!” The print included title cards denoting the conclusion of each reel. By the time the third had passed, the entire audience was audibly counting.

Opening with a little prologue by Mrs. Wallace Reid, warning the audience not to enjoy any of what was about to follow, the film, effectively imitative of Greed in many places, told the story of a lovely 12-year-old girl fallen victim to the white slave racket. She is spirited to New Orleans and made to wear the red kimono. Years of unspeakable degradation pass. Bonner’s pimp leaves. She pursues him to L. A., and, finding him in a jewelry store buying a ring for another woman, kills him. Swiftly acquitted and taken in by a society woman (bearing an interesting resemblance to Mrs. Reid) who wants to show her off at cocktail parties, she falls in love with a kindly chauffeur, but, kicked out by her benefactor, drifts back to the streets, and finally catches the train back to the brothel, one step ahead of the chauffeur, and then—“And then the War began” read a title card. The audience nearly croaked, terrified at the prospect of sitting through at least an entire world war before there would be the slightest chance of finding out what happened to poor Priscilla. Luckily, the whole story was swiftly wrapped up in a crescendo of patriotism, true love, and expiation of guilt.

Anger, who had brightened the final decades of the film with a barrage of very funny one-liners, was just getting warmed up. He was glowing. There was something magical in almost everything he put on the screen, and he seemed possessed by the magic, by the mystery that adheres to the best (and even some of the worst) silent films as it does to no film made since sound came in.

“Alma Rubens!” he shouted, after a brief view of the lovely OD victim Barbara La Marr. “You will see Alma Rubens expire of morphine poisoning before your very eyes!”

And we did. There she was, Alma Rubens, one of the most uniquely beautiful and touching of all ‘20s stars, dead of morphine in 1931, appearing before us in an obscure 1928 Henry King film, She Went to War. The scene was a barracks, somewhere near the German front. As the astonishing Eleanor Boardman (King Vidor’s first wife, featured in The Crowd) wept in a corner, Rubens sang her heart out to a dying soldier, but in truth, she was all too obviously dying herself. The mood shifted violently; from the near-camp moralizing of The Red Kimono we were confronted with a horrifying interplay between the fictional images of the screen and the tawdry reality that was, frame by frame, replacing them. It was a brilliant setup and it hit hard.

There will undoubtedly be much that I haven’t mentioned and much that I didn’t see when Anger brings his show to New York this winter—perhaps all of She Went to War rather than a short clip—and the presentation, quite effective in Berkeley, may be even more spectacular. In many ways much stronger, and a good deal more fun, than Anger’s book, the show is of a piece with his own films—cracked down the middle, forcing an audience from one side to the other, mixing voyeurism with a fervor that can only be called religious. As such, Anger’s show was the best Black Mass in town. Wherever it plays, I guess it will be that if nothing else.

Originally published in The Village Voice, October 13, 1975

Judging from Greil's article, I too would have found the presentation of Hollywood Babylon more enjoyable than the book, which degraded its subjects.

Anger wouldn't have been able to show all of Henry King's "She Goes to War" (1929), because the original version—105 minutes and mostly silent—was hacked to pieces and reassembled into a 50 minute sound reissue. What survives is a jumble of sound scenes from the original and several impressive (and literally infernal) combat scenes.

Wow! This is terrific. I had never read this. I agree - "Rabbit's Moon" is one of the greatest films ever made. I really wish I had been there at this historical event. You were lucky you were there. [This post did inspire me to search online for all the films and clips mentioned so I could commune with Anger's spirit - not that he gives a shit.]